As many people are becoming increasingly disillusioned by a tumultuous political arena and a lack of social mobility, many are turning towards the gym as a way to “cope” with capitalism and achieve objective “positive” results.

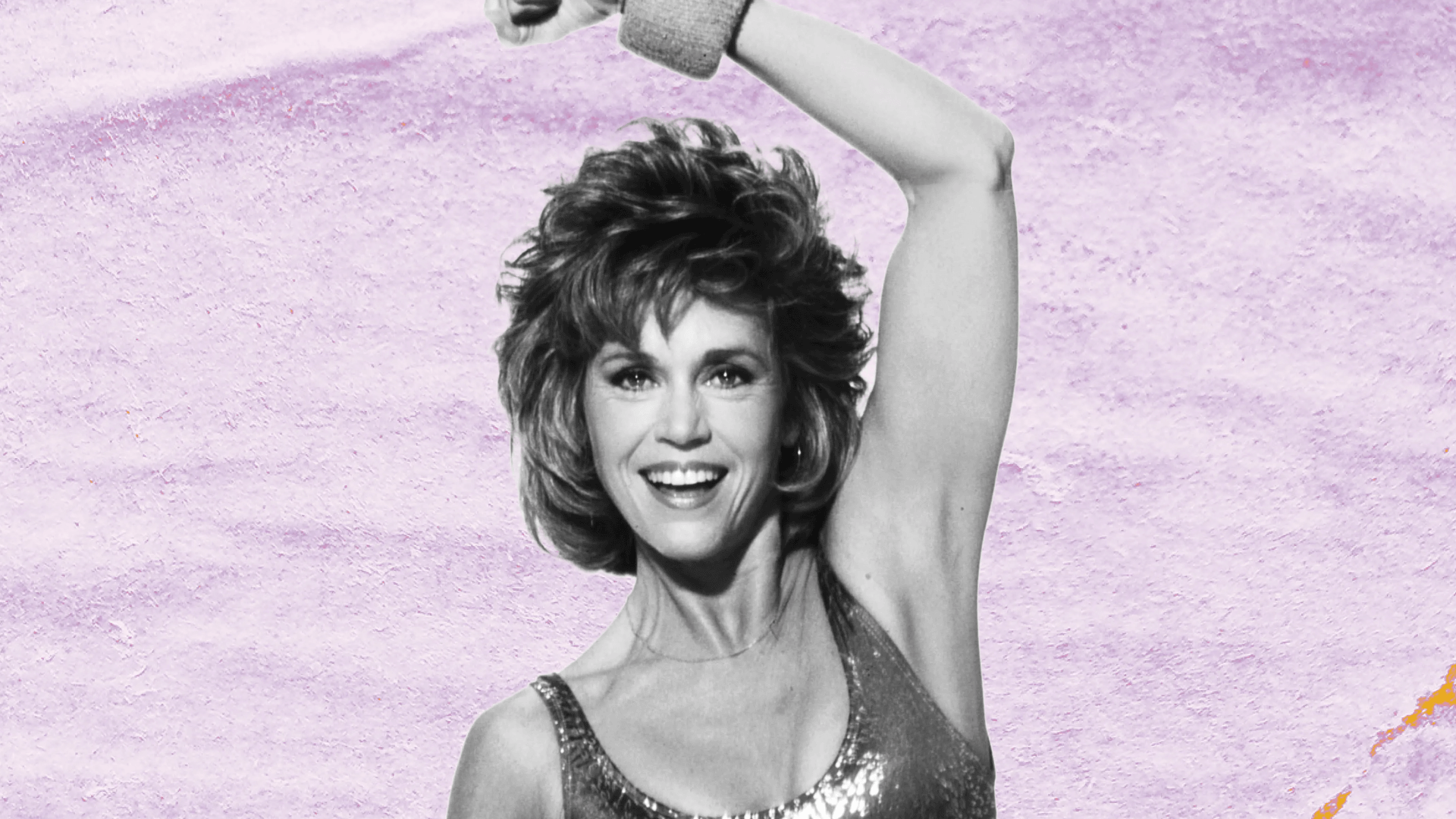

In 1982, Jane Fonda’s at-home workout videos were released, becoming one of the most popular nontheatrical home videos in the world. As well as her choreographed fitness routines, Fonda also experienced success as an actor, starring in films since the 1960s.

Prior to her on-screen fame, the workout wonder was consistently vocal in her political activism against the Vietnam war and violence against women, and in support of the civil rights movement. Fonda remains respectfully outspoken and committed to her political beliefs today.

However, as documentary maker Adam Curtis has noted, her manoeuvre into the world of marketised exercise carried some of the connotations that suggest while you may not be able to control the body politic, you can have (some) control over your body.

Economist Gary Stevenson has raised similar ideas, suggesting that some men’s obsession with the gym – and how much they can lift – serves as a substitute for their inability to control their social mobility.

As elite circles have become increasingly gatekept and, for want of a better word, inbred, we’ve seen the sociological concept of social mobility and meritocracy superseded by nepotism – of which, regrettably, Fonda is a product.

Capitalist society houses an intense focus on hustle culture espoused by the likes of tech-bros and self-professed “bio hackers” on the internet who create content that teaches people, effectively, how to beat the competition.

Yet, as Stevenson points, only in the gym are you often actually guaranteed to see “positive” results.

Exercise is a business

It goes without saying that the political ideologies of gym-obsessed wannabe business hustlers, and activists like Jane Fonda, are separated by a vast chasm in terms of priority.

Yet, as the poorest UK households are subject to higher rates of council tax, and both fascism and misogyny are rife, it’s no wonder that the attraction of direct physical results rather than potential political disillusionment might appeal to both.

This emphasis on observable and objective results for the individual as a substitute for collective political liberation in particular speaks to the 2022 text Fabrique du Muscle, in which French sociologist and author Guilleme Vallet compares the gym to the factory.

He describes both as a place where you clock in several times a week, lift heavy machinery, and then go home to rest before doing it all again in the succeeding days.

Vallet uses this comparison to argue that many fitness fanatics use the effort exerted at the gym to compensate for the lack of control they have outside of it.

The truth of this analogy resonates thanks to, as Vallet says, the integration of a space like the gym into a society which goes beyond it. We see this in the ways that the gym, like a job, impacts not only our physical bodies, but also our nutrition, our social relations, and ultimately, our priorities.

Historically for various reasons, including but not exclusively, misogynistic attitudes towards physically strong women and the double burden that disproportionately impacts women, (having the time for) weightlifting has been viewed as a predominantly male activity.

It goes without saying that all genders ought to be able to seek benefits from weight lifting if they wish to. However, the pressure to succeed and the subsequent compensation sought in the gym for what is perceived as societal failure is most experienced by men thanks to patriarchal pressures which wrongly cast men as the archetypal protector and provider.

Issues of social class which mean social mobility is less available to those from a lower starting point are repackaged to men as a personal failure. Meanwhile, a “solution” is literally sold to them in the form of a gym membership.

A slim chance of success

Of course, there are and have always been strong women, both physically and ideologically.

In modern day female fitness culture, the shift from exercising to be ‘thin’ to exercising in order to ‘grow’ is pervasive.

Nevertheless, even in today’s more progressive culture there remains an expectation – and a statistical backing – that the successful woman is the one who remains physically attractive, conventionally desirable, and, above all, slim.

Women like Jane Fonda advocate healthy living and fitness, which includes physical strength in a mode that differed from the previous normative expectation that women ought to be slim and delicate. Nevertheless, it would be blatantly untrue to deny that Fonda herself already fit the so-called “ideal” of the slim white western woman – as did all of her co-stars.

Although many people of different genders use exercise as a way to “cope” with capitalism, it seems that the underlying expectation that these efforts should also increase your desirability by decreasing your waistline – an element of fatphobic society – still disproportionately affects women more than men.

Undeniably there are more spaces which women have forced their way into in modern day society thanks to feminism than there have been historically.

Yet this gender disparity still makes obvious that the spaces themselves are undeniably smaller. This is especially the case given the recent resurgence of heroin chic and the associated iconisation of the y2k skinny physique.

Whilst men mimic social mobility in the gym through increased muscle mass, women seem to be emulating their subjugation by literally making themselves smaller – and in doing so often weaker – so as to appear more desirable within the confines of this system.

Short term – as we’ve seen equally in trad wife content and with the rise of OnlyFans – it may seem possible to manipulate the system for your own personal gain. Monetising your desirability through various forms of sex work allows many people to find a form of (otherwise unavoidable) capitalism that works for them.

Likewise, living in accordance with certain normative beauty standards may not seem so bad if your beauty treatments are funded by a rich husband and the kitchen you’re confined to has all the latest culinary equipment.

On the flip side, this approach does little to dismantle the system as a whole. In the case of Only Fans, for instance, while the highest earnings are becoming millionaires, the majority of content creators on this platform make barely enough to be taxed on it.

Ultimately, reaping the benefits of a patriarchal system encourages indulgence and a narcissistic self-obsession, only to force us to succumb later to the self imposed expiration date these “benefits” place on our value as women. This takes the form of purchasable products which enable us to extend our subscription to the desirability of ourselves through cosmetic surgeries, gym memberships and organic foods.

The unthinkable alternative would be to just live our lives – which we get for free, by the way.

It doesn’t matter how expensive your moisturiser is or how many reformer pilates classes you go to. If youth and beauty are the only things you deem valuable about yourself then old age will arrive as a dreaded yet unavoidable fate.

All of this, then, is why the 2024 film The Substance directed by Coralie Fargeat, was, in my humble and extremely young opinion, so powerful.

The Substance

The Substance depicts Elizabeth Sparkles (played by Demi Moore and based on Jane Fonda) unable to control the perception of herself in the patriarchal, capitalist driven society around her which she had previously enjoyed benefitting (?) from.

In order to combat her feelings of abandonment as she is dropped by the label which made her name for a younger, prettier model, Sparkles purchases an injection – cleverly presented illegitimately to her by a doctor as if it were some sort of illegal medical procedure, like a BBL, but more dangerous – which unlocks the younger, more conventionally attractive version of herself (played by Margaret Qualley).

Sparkles becomes a victim of the ageist and misogynistic systems in place which seek to oppress and rob her of everything her desirability within this system had enabled her to build under the illusion that her so-called privileges would last. Instead, this system, which abandons her as soon as she shows any visible signs of ageing (or in any way deviating from this strict ostensible societal contract), results in Sparkle’s own internalised self-loathing.

The film extrapolates, in all its cinematic gore and glory, the consequences of turning your head away, of smoothing out the wrinkles and hiding from reality rather than seeking to remonstrate with these systems of control which run on mass exploitation and individualistic competition.

To reform or to revolt, therefore, remains the ultimate “woman question”.