Sabrina Carpenter began to receive criticism for her most recent album before it was even released in full, many people taking umbrage with her ‘submissive’ pose in the cover art. But is Sabrina catering to the male gaze, or is she turning round to stare right back, and to charge people for the privilege?

The criticism for Sabrina Carpenter’s latest album cover art has been far reaching and pervasive.

As Charlie Coombs has already explored prior to the release of Carpenter’s ‘Man’s Best Friend’, everyone from fans to commentators have, apparently, been waiting to pounce on this particular internet debate.

All else aside, it’s been an excellent marketing strategy by Carpenter’s team.

The art in question features the 26-year-old pop singer on her knees, in kitten heels and a LBD (that’s a Little Black Dress for anyone who hasn’t heard of Chanel). A suited man stands mostly out of shot holding up a lock of Carpenter’s iconic blonde hair.

Much of the criticism for this artistic choice has focused on Carpenter’s supposed glamorisation of female sexual subjugation. As Charlie quotes in his article, one Reddit user said, ‘she’s not beating the ‘catering to the male gaze’ allegations, what are we doing here?’

Meanwhile, another commenter wrote, simply, ‘girl – stand up!’

Of course, as with any discourse, Sabrina has her supporters. Amongst them is Helen Coffey, a journalist for The Independent. Coffey’s impassioned article in defence of Sabrina’s artistic integrity denounces any notion that the album cover could be at all, in any way, ‘submissive’.

Through the invocation of lyrics from Carpenter’s previous albums, Coffey writes: ‘whether it’s by effortlessly seducing the man she wants in Espresso or looking down at his stupidity with world-weary ennui in Sharpest Tool and her new single, Manchild, Carpenter always comes out on top.’

Indeed, it’s hardly a stretch to see the satire in the album’s construction, which, as Coffey also points out, was written, imagined, and performed by Carpenter herself.

This is evident if not from the cultural zeitgeist which frames its release, then from the Fleabag-esque breaking of the fourth wall; Carpenter, with her heavily lashed, sparkling eyes, extends the intimacy not to the suited figure above her, but to us, the voyeurs.

Understanding the Fleabagism of feminism

Written and acted by Phoebe Waller-Bridge, Fleabag cultivates a similarly meta relationship with its audience. The fourth wall is routinely broken in order to comment on the ridiculous situations the female protagonist finds herself in, usually at the expense of another (often male) character.

This tactic has been reimagined by other female leads too, such as Dakota Johnson’s almost offensively distasteful performance as Anne Elliot in the 2022 adaptation of Jane Austen’s Persuasion.

Austen’s novels satirise the middling society in which she lived, often incorporating small acts of subversion into their narratives. These moments allow for a rolling of the eyes at the oppressive systems that are beyond our control, providing brief solace from an unchangeable situation.

In the Manchild music video, is this feminist smirk not at least a little bit recognisable?

Sabrina attempts to take advantage of men’s tendency to want to help women when they present themselves as vulnerable in various different situations, but moves on to the next after each ‘contestant’ proves incompetent.

This includes hitchhiking, robbing a shop, and even a shootout with police. Why doesn’t Sabrina just do these things herself, we might wonder?

Carpenter, in real life, is an internationally acclaimed, extremely successful, wealthy pop star. If men keep disappointing her, then why shouldn’t she, as a woman, be able to get what she wants and take control of her own life without worrying about men at all?

The fact that she doesn’t is clearly a deliberate comment on the patriarchal systems which still oppress women and impede their access to many of the opportunities available to men.

What’s more, so what if Carpenter does take pleasure in her desirability? Does that negatively impact her role and identity as a feminist?

The truth is, we live in a society and economy which profits from the exposition of women for men’s enjoyment, be it overtly through the sex work industry or through free entry for women in night clubs, of which 91% of female students reported having been sexually harassed in 2016.

When so many women have been raised with the message that we need to dress or act a certain way, that everything we do could potentially deter, or entice, male attention, can you really blame women like Carpenter for monetising it, especially in line with the economic systems introduced and pervaded by men?

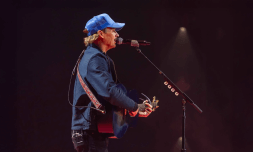

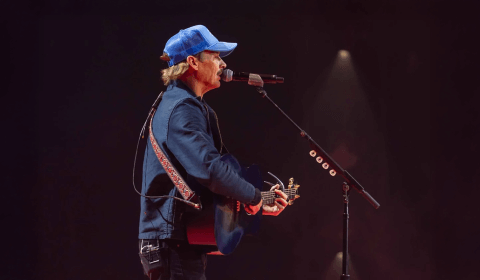

Sabrina is known for her uber-femme dress sense, sporting high heeled go-go boots and sparkly numbers on stage. She re-enacts a different sex position each night of her tour and replicates the iconic looks of female celebrity icons such as Marilyn Monroe and Madonna when on the red carpet.

Given all this, it would be difficult to make the case that Carpenter wasn’t aware of the outrage that some of her creative decisions have sparked.

@invisblestrings juno paris n2: the eiffel tower edition #sabrinacarpenter #shortandsweet #parisshortnsweet #juno #eiffeltower @Sabrina Carpenter @Team Sabrina ♬ original sound – 𝖏𝖆𝖘 ⚔️

But through the lens of female sexual empowerment, the now infamous album cover is just another item in the long list of subversions Carpenter is using her platform to carry out.

At first glance, the sex positions and burlesque stylisation may seem like something from the pages of Playboy, especially when she posted a TikTok in a literal, glittery Playboy bunny outfit. When you look closer, however, the theme becomes more obvious.

Fleabag is described by author Sohel Sarker as ‘breaking new ground’ in feminism. Sarker notes that Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s character in the show ‘rejects the mantle of “nice girl” in order to affirm an imperfect womanhood,’ later describing this as ‘undoubtedly a feminist act.’

Carpenter’s carefully-constructed public image similarly follows this template. The difference? Sabrina isn’t consumed by self-loathing for expressing sexual desire in the same way that Fleabag is.

As Celeste Davis points out in a Substack essay, the female archetypes and their public images that Carpenter has chosen to invoke, such as Marilyn Monroe, Madonna and even Jessica Rabbit, have all been subjected first to sexualisation (by men) and subsequent condemnation for the type of woman they portray.

That is, one who dares to enjoy the attention they receive and uses it in place of the privileges they don’t have. Who refuse to claim a feminism that fits neatly within the parameters already laid out by years of gender oppression.

Arguably then, like the ‘harlots’ and ‘sluts’ before her, Carpenter takes advantage of her limelight in the male gaze. At the same time, she makes a mockery of those gazing – both in lust, and disgust – who have bought into the idea of weaponising women’s sexuality.

View this post on Instagram