The rise of casual trauma discourse in digital culture

In the digital age, emotional awareness and trauma discourse are unfolding in real time, in ways and at a rate never before seen.

Instead of trauma being an underlying force in political movements, it has moved to the surface of cultural conversations, with even our youngest users accessing and utilizing language that their parents and grandparents either wouldn’t have been able to define or would avoid using at all costs.

Mental health challenges, their symptoms, and their clinical diagnoses are seemingly common knowledge in today’s world, at least to some extent. It’s also important to note that the prevalence of experiencing or diagnosing mental illness has risen as well, with 1 in 5 Americans experiencing a mental illness annually.

On the one hand, we can acknowledge that de-stigmatization has played a role in more people seeking resources and support, and even more so, we must acknowledge how our media has shaped that evolution. More and more users are sharing about their experiences or educating audiences on mental health symptoms online.

Platforms like TikTok accelerate emotional literacy (but also have the potential to spread misinformation [e.g., Can We Trust Autism Information on TikTok?], but that’s a conversation for a different day).

On the other hand, this trend toward emotional literacy is evocative of a shift toward the desire to heal. Through digital mental health trends, we see a generation trying to understand, grapple with, and challenge the traumatic wounds left behind from generations of systemic oppression. To the point where emotional literacy and trauma-awareness have seemingly become casual, sometimes even viral. [This article might even suggest contagious].

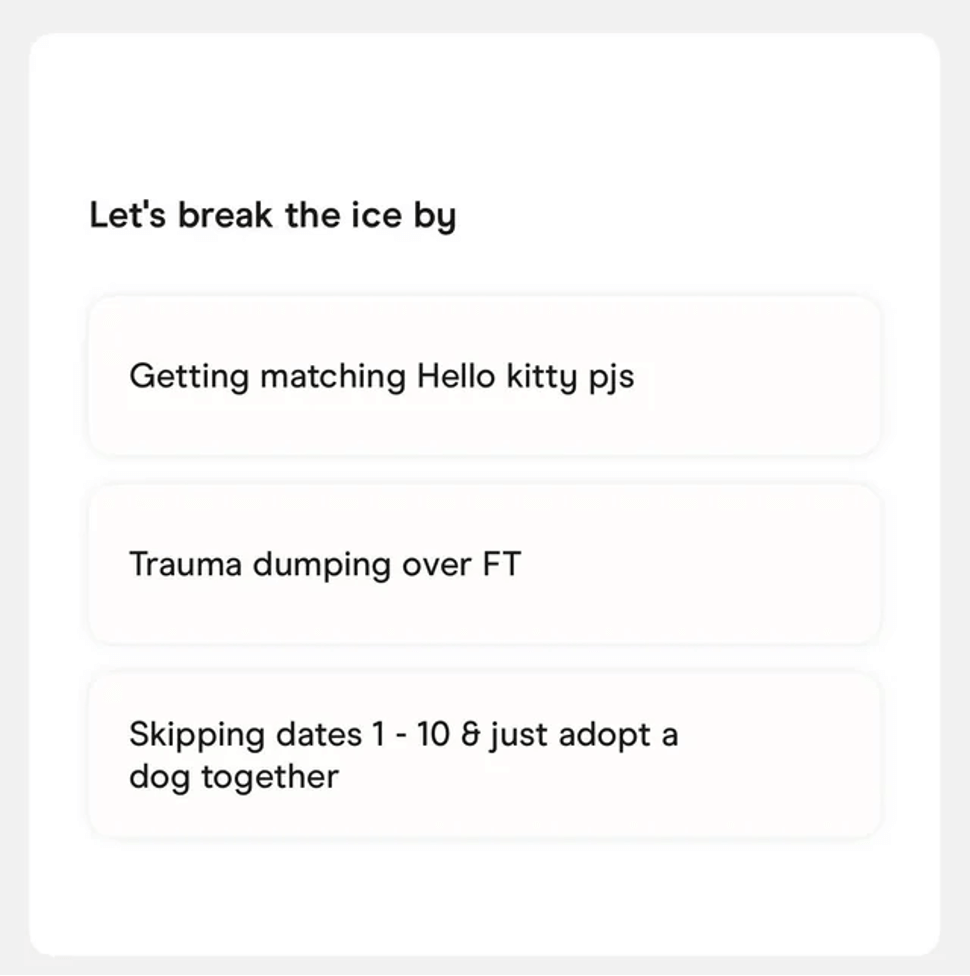

Phrases like “gaslighting,” “attachment styles,” and “trauma-dumping” have entered everyday conversations and dating app bios.

Unlike previous generations, Gen Z is navigating emotions in an era where TV shows, social media, and dating apps act as both an emotional mirror and an amplifier.

What does it mean when people ironically or performatively reference trauma in their self-presentation? To the point where this level of vulnerability and openness is actually used as emotional fodder and social currency to attract a potential partner?

It indicates that awareness isn’t just shaping our self perception or psyche but actually manifesting in changes to our behavior, our actions, and more importantly, our interactions.

The media mirrors Gen Z’s emotional navigation

Whether it be through Tik Toks, TV shows, or tweets, we are seeing media turn into emotional playgrounds. It’s a cycle. Shows reference and normalize mental health, and mental health in real life informs the storylines of shows.

For example, take this scene from HBO’s Sex Lives of College Girls. During the episode in the latest season, the main characters are hosting their parents during parents weekend. The dinner conversation among the friends and their parents centers on Gen Z’s prevalence of therapy (a topic that in and of itself is evidence of a trend toward mental health treatment, knowledge, and normalcy among young people).

The parents suggest that therapy is overblown and not every needs therapy, all the while the girls are texting each other the following commentary:

Bela: “Here comes the boomer mental health takes. Whose will be worse? … generational trauma and a culture that shapes any display of emotion.” Meanwhile, the parents are saying things like “our generation never knew the word ‘triggered,’” in the background.

Treatment of trauma, mental health, intergenerational differences, transgenerational trauma… all normal here. This text exchange offers a moment of deep emotional insight wrapped in humor.

It is evidence of this casual trauma-awareness and emotional knowledge that marks the Gen Z experience and how that’s spotlit among the backdrop of the boomer POV. The language and casualness evidenced in this scene reinforces the knowledge, language, and casualness among its audience.

As it relates to mental health, what’s seen as normal on screen is normal off screen, particularly toward young people (some could argue for better or for worse, but again, that’s a comment for another day). Sex Lives of College Girls and other shows that center therapy-informed storylines are wildly popular.

The shift from traditional “drama” to psychological complex narratives (Europhia, Shrinking, BoJack Horseman) aren’t fringe, as they may have once been. They are the spotlight. They are award-winning. They’re all-consuming, and even the most extreme narratives shed light on emotional literacy or trauma to young audiences, as is the case with Euphoria.

The question then becomes: does seeing therapy discourse everywhere deepen emotional intelligence or trivialize it?

The paradox of emotional intelligence vs. emotional numbness

Gen Z, having come of age during this shift and becoming equipped with years of reinforced emotional knowledge, is especially talented at describing their emotions, particularly young women. The language wielded by young people would seem to suggest that they know what and how they are feeling. When, in reality, the opposite may be the case.

Despite the televised nature of revolutions, as Lamar suggests, and the millions of diagnosis TikToks or thousands or modern therapy references on TV, this heightened emotional awareness has only allowed us to intellectualize our feelings, rather than to actually feel them. Are we using language as a shield rather than engaging with the emotions themselves? Is this newfound emotional literacy a tool for real healing, or is it performative?

In naming our feelings, we face a deeper, different sort of paradox: with self-narration comes, ironically, emotional detachment. This doesn’t distribute equitably, either. Young women are often more emotionally fluent but still struggle with burnout and hyper-intellectualization.

Where our platforms might give us the vocabulary behind our feelings or our trauma, it does not give us the tools to process them. This begs the question: Are we truly processing our emotions, or just branding them?

Is Gen Z too emotionally literate to feel?

We’ll scroll past the revolution if we don’t pause to process it.

![]()