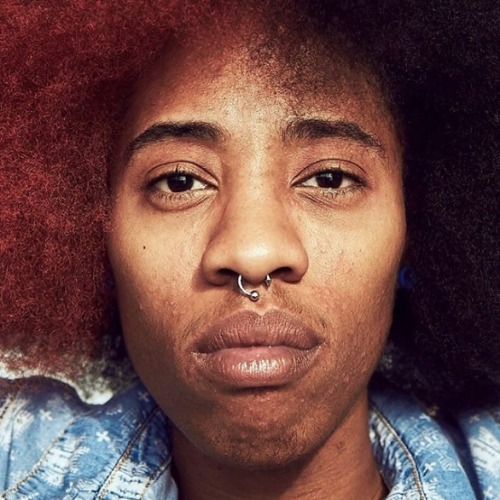

Nonbinary artist Soraya Zaman’s latest project, American Boys, redefines our notions of masculinity for the 21st century.

Australian born photographer Soraya Zaman identifies as gender fluid, and they’ve made the search for identity that accompanies a queer individuals identity politics a central tenant of their art. According to Zaman in an interview with ONE37pm, ‘the best work is a reflection and an exploration of what is personal to you, your identity and how you see the world.’

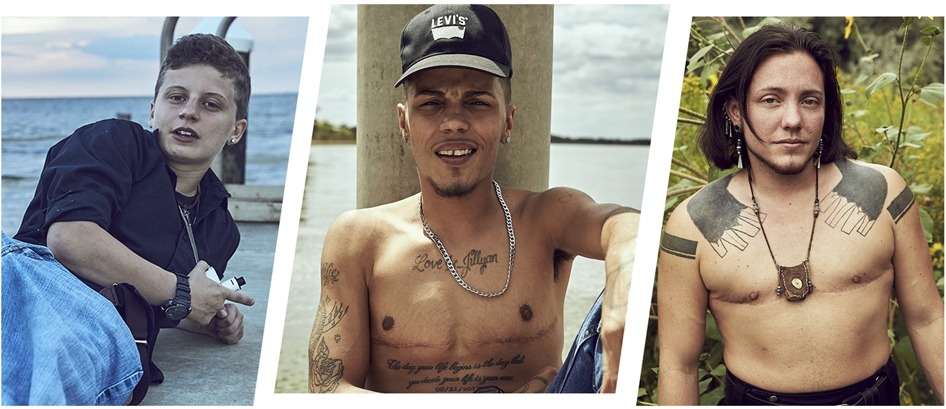

Though they identify as fluid, Zaman is masculine leaning, and they explore the concept of masculinity in their portraiture series American Boys. The project features 29 individuals from across the USA in various stages of female to male transition. Some images depict close ups of week-old top surgery scars, and others outline reclining male figures so far from surgery that scars are no longer visible. Some portraits are of transmasculine individuals who haven’t undergone surgery at all.

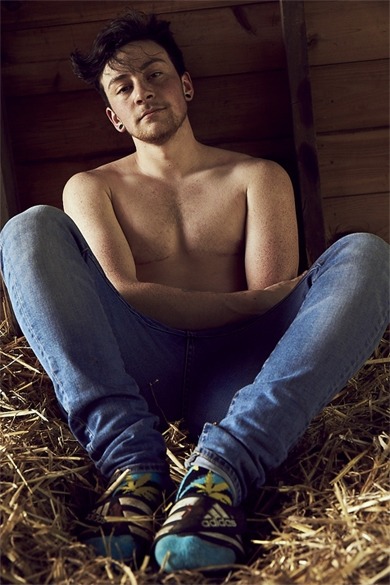

The unifying thread that unites all subjects is their identification with a masculinity they were not assigned at birth. These individuals pose in myriad ways, with pensive gazes and furtive glances shot from below outlining a vulnerability that’s placed in direct contrast to individuals who stare down the camera with an electric energy that speaks of an overwhelming sense of selfhood.

Bodies are placed both in delicate ballerina-like poses traditionally associated with femininity, and in the legs-wide-open, scowling challenge of ‘traditional’ masculinity.

It’s evident that Zaman’s point has to do with the performativity of gender. These individuals embody (quite literally) their sense of self in a project explicitly about gender. They typically stare directly into the camera in an act of direct communication with the viewer. Zaman’s message is not the innate ‘maleness’ of these trans men or how they confirm their masculinity through furtive, private moments, but about how they choose to present themselves to their world.

They offer their masculinity to the viewer as a kind of test, as if daring them to look twice at the scars or small lumps on their chest that testify to the fact that they did not always look like this. The scars are a reminder of the journey these people have gone through to realise and execute the identity they now present with confidence.

The frank depictions of surgery scars are both refreshing and confronting. It’s rare that the cisgendered person gets a closer look at the scars of transition, and it reminds us of the challenges and pain the trans individual must go through to crystallise their true self. It reminds us of what Zaman calls the ‘level of bravery requires to exist as a trans person’.

Zaman states that for the project they were determination to capture trans men from both big cities and small towns. It was important to them to ‘feature transmaculine lives all over the country and not just represent people who live in New York and LA and other places typically thought of as queer hubs’. A universality in the midst of individuality comes through strongly – a microcosm of a community fighting for complete and unmitigated acceptance.