Getting the facts straight

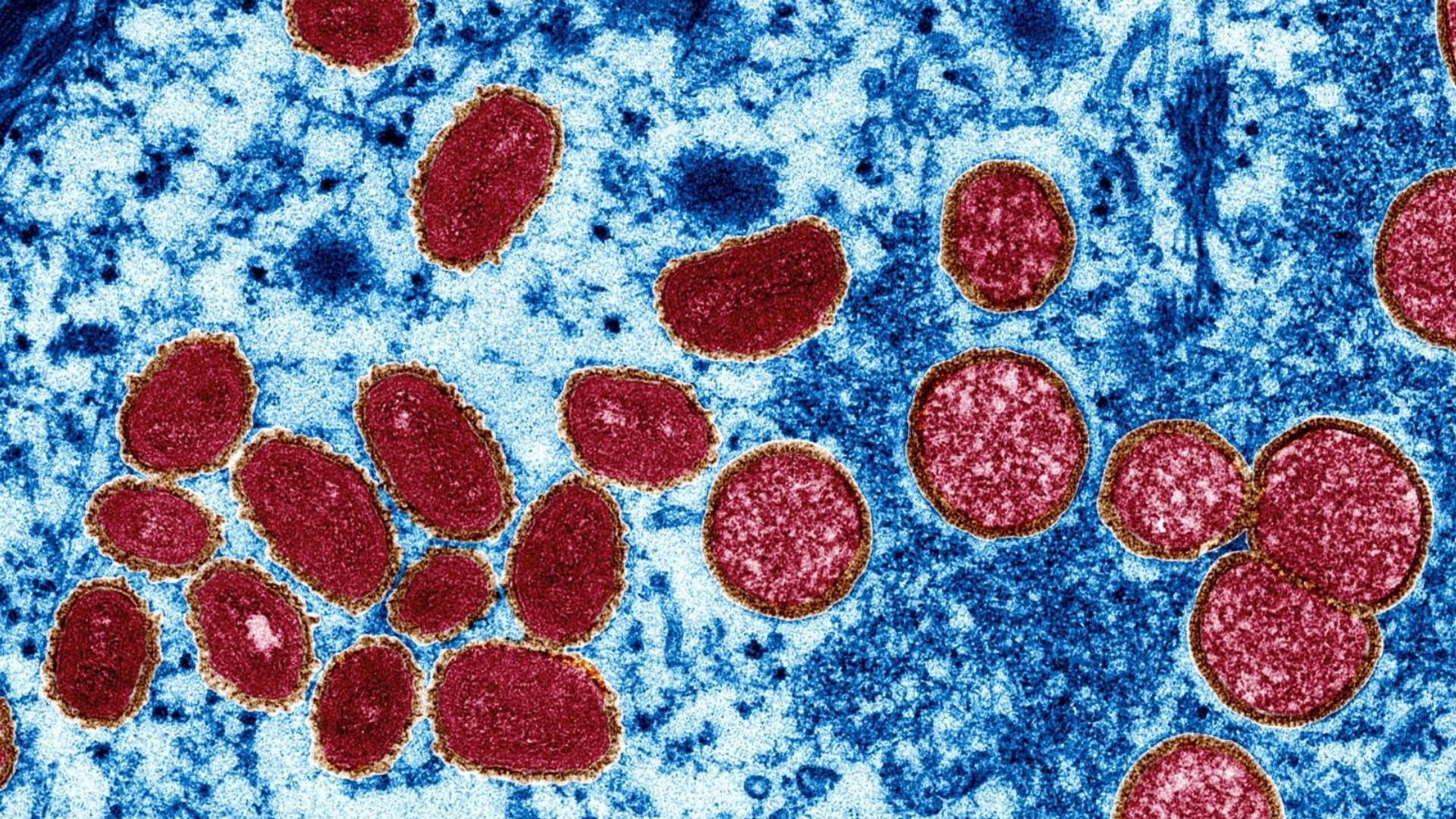

When news was first raised in May about a new outbreak of monkeypox, an emerging pattern showed that cases were mainly identified amongst gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men.

While it’s true that monkeypox can be transferred via bodily fluids – making it easily transferred through sexual activity – monkeypox is not exclusively a sexually transmitted infection (STI).

Monkeypox is also spread through direct contact with the infectious skin rash or scabs of an infected person. For example, if someone is in a crowded space and rub arms unintentionally with another person who has monkeypox, it’s highly possible they might catch it.

It can also be transmitted through respiratory secretions during prolonged face-to-face contact, whether that’s spit droplets while talking or close physical contact such as holding hands, cuddling, kissing, or, as mentioned, sex.

Caretakers and roommates of those infected are also at risk, as the virus can be contracted through contact with items that previously touched the rash or other bodily fluids – this includes clothing, shared towels, or bedding.

Though unpleasant, monkeypox is treatable, and there are vaccines already being rolled out – albeit in small numbers – to protect those most at risk. And although its symptoms are often compared to smallpox, monkeypox is far less severe. Of the 16,000 cases reported in 75 countries, there have been no fatalities.

Despite this, suggesting that people outside of the LGBTQ community are not at any particular risk of contracting monkeypox is problematic. It creates stigma for those within the community, while omitting the scientific facts about how the virus can be passed on.

Tracking the medical response

Though comparing different viruses is like comparing apples to oranges, it’s important to look at past approaches to virus control in order to be better prepared for the future.

After COVID-19 broke out, health officials said that slow-to-act governments had repeated the same mistakes they made during the AIDs outbreak of the 80s and 90s.

A disjointed and uninformed response from local governments allowed COVID to spread from isolated areas across entire countries and – as we know – eventually around the whole world. This ‘wait and see’ attitude plays a huge part in allowing misunderstood viruses to reach global populations.

And although the large majority of monkeypox cases have emerged amongst ‘men who have sex with men’, the messaging around monkeypox has drawn criticism for ‘damaging, stigmatising’ and ‘misleading,’ as it targets a specific group as ‘the spreader’ while telling the rest that they should, in theory, be just fine.

In regards to framing monkeypox as an illness that affects the LGBTQ community exclusively, Lauren Beach, a research assistant professor at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine said:

‘Monkeypox, like any other transmissible condition, can be spread wherever the virus is allowed to thrive. Any human is going to be susceptible to monkeypox, and so, I think that if we just attribute the virus to a certain set of people, like LGBT people, that could result in stigmatizing LGBT people as carriers of a plague, when we see that happening before with HIV.’

What can we learn from the outbreak?

The point of this article is not to fearmonger people into re-selling their festival tickets or avoiding crowded spaces over worries about monkeypox. Getting a better understanding of the virus, stifling stigma towards the LGBTQ community, and learning from the past is.

Experts have criticised the US government for downplaying the initial outbreak in Europe, saying that warning signs were ignored. ‘We [the LGBTQ community] are on our own as always. We can’t count on anyone else,’ State Senator Scott Weiner told the LA Times.

Right now, vaccines are on the rollout for men within the LGBTQ community, but appointments are reportedly being approved according to a ‘strict criteria,’ meaning numbers already administered remain low and sparsely available.

There are concerns that high-risk individuals living in low-income areas will lack ease-of-access to vaccines, as it is already notoriously difficult for members of the LGBTQ community to receive proper healthcare, especially in America.

In California, one of the country’s most liberal states, healthcare plans for low-income communities don’t currently cover testing for monkeypox and at the time of writing there is no financial aid for those forced to isolate with the virus.

In response to the growing outbreak, LGBTQ leaders are demanding more testing, vaccine sharing, and the onboarding of additional health workers to help control its numbers. Encouragingly, governments say that hundreds of thousands additional doses will become available in the coming weeks.

In the meantime, I recommend reading this brilliant, honest, and informative piece by Kyle Planck, a PhD student based in New York, who describes his recent experience with monkeypox.