Fashion may empower the women who wear it, but it needs to start empowering the women who make it too.

A quick google search of ‘feminist clothing’ yields about 38.5 million results. Most of these are shopping posts, linking you to slogan tees with phrases like ‘woman up’ and ‘smash the patriarchy’ on them. My personal favourite is a black tee with white writing ‘quoting’ Rosa Parks – ‘Nah’.

These tees are cute. I find myself picturing how they would look paired with items from my wardrobe. The seduction of fashion finds my brain wondering at odds from the reason I googled the phrase in the first place. I wanted to see if the phrase ‘feminist clothing’ would pull up a discussion of the actual feminist issues innate in clothing production and garment work. It’s not until the third page that I find one by HuffPost – an article questioning whether your favourite feminist merch actually does more harm for women globally than good.

Of course, by now most people are already at the Zara check out with a ‘the future is female’ tote in their basket.

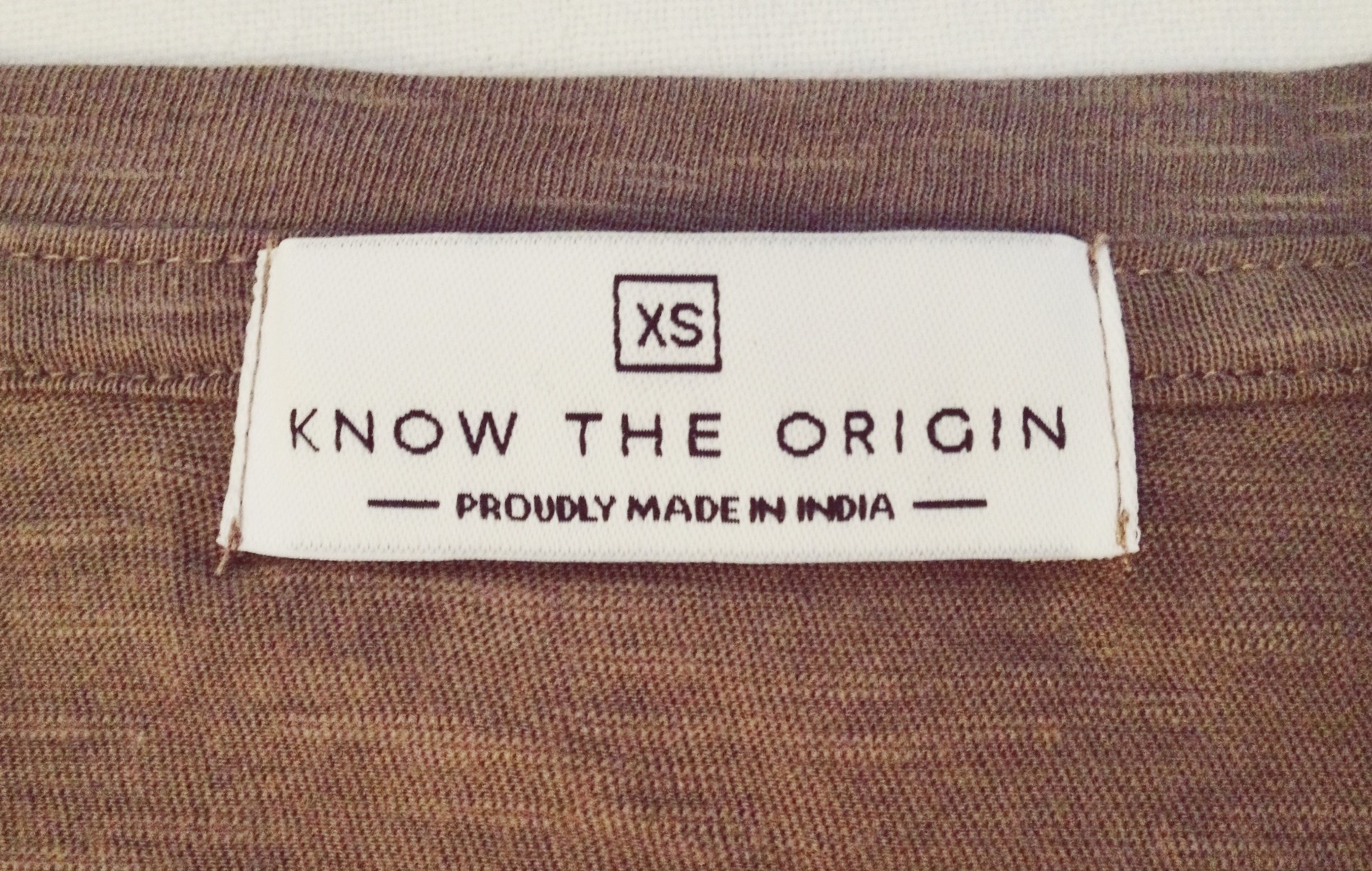

None of the supposedly ‘feminist’ clothing items on the search offer the key detail that could actually prove their feminist qualifications: information about where they were made, who made them, and under what conditions.

According to Labour Behind the Label, 75-80% of garment workers around the world are women aged between 18—35. Due to the gender pay gap (a disadvantage significantly exaggerated in the developing world) and lax labour laws, female garment workers often work for a fraction of minimum wage and are subjected to unsafe conditions. This report on a factory in Cambodia found that poor ventilation, lack of access to water, overwork, and chemical exposure had led to significant health problems in the factory’s workforce, the majority of whom are, or course, women.

The world has perhaps never paid as much attention to the plight of sweatshop workers as it did in 2013, when an eight-story commercial garment building called Rana Plaza collapsed in Bangladesh, killing 1143 people and injuring 2500. Workers reported that on the day of the collapse, they’d expressed concerns about the cracks ripping down the walls of the workshop and the strange moaning noises emanating from the roof. ‘Managers hit workers with sticks to force them into the factory that day’, said Judy Gearhart, the executive director of the International Labor Rights Forum.

80% of those killed were women between the ages of 18 and 20, forced by poverty to work in the factory for 22 cents an hour.

As the monolith of grey concrete poured itself out onto the Bangladeshi street, the eyes of the world turned to the companies whose names could be found amongst the labels in the rubble. The penurious Rana Plaza, it turned out, serviced a panoply of multi-billion-dollar brands such as Mango, JC Penny, and Primark.

Suddenly, the fortunate opacity of the capitalist production line came crashing down and the reality of worker exploitation was brought directly into our living rooms. ‘But I shop at Primark!’

After Rana Plaza, Bangladesh implemented a massive safety inspection and remediation program, and as of today more than 1000 of the factories covered by the accord have sufficiently addressed 90% or more of the safety issues raised in the places of work, according to independent inspection bodies.

As such, the West’s concern and outrage had proved fickle, our shopping habits seeing little change. UK consumers sent 300,000 tonnes of textiles to be burned or dumped in landfill in 2018, and according to a 2019 study conducted by McKinsey & Company, one in three young women in the UK still consider an item of clothing worn more than once or twice to be old. It seems that our taste for fast fashion is picking up speed, not slowing down.