Olive oil production falls sharply

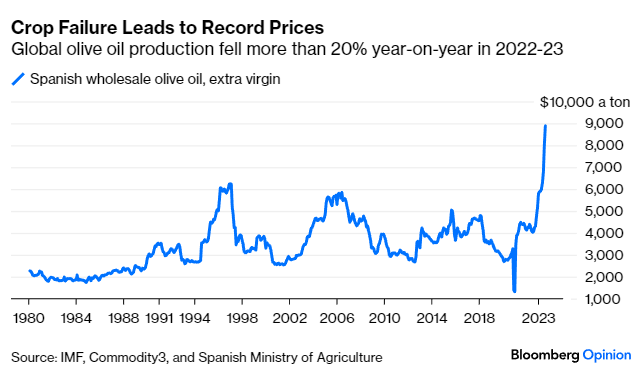

I probably don’t have to tell you that the price of olive oil has suddenly skyrocketed.

Spain, the world’s leading olive oil producer, typically generates 1.4 million tons of the product each year. Around 46 percent of this is exported to other countries, supplying almost half the world’s olive oil.

But the European nation has been experiencing serious droughts in recent years. Low rainfall in 2022 and 2023 led to a 50 percent reduction in its olive oil production. spelling out an inability to meet global demand for this precious food oil and higher prices for consumers.

It could also signal an end to dishes which rely on Spanish olive oil such as allioli (garlic mayo) and gambas al ajillo (prawns in olive oil).

One tequila, two tequila, three tequila… no more

Agave plants growing in Mexico are essential to creating two of the world’s most popular spirits: mezcal and tequila.

But these plants rely on being pollinated by a special animal, the Mexican long-nosed bat, which is facing extinction in the region. Its natural habitats are disappearing and its food sources are dwindling as temperatures rise higher.

Conservation experts have explained how the relationship between these bats and agave plants is entirely symbiotic. They say that losing one ‘would threaten the survival of the other’ as this is the only animal that pollinates the blue agave plant.

Even if growers were to farm and manually pollinate blue agave in another region, they would not be able to label their product as tequila.

Mussels missing from the menu

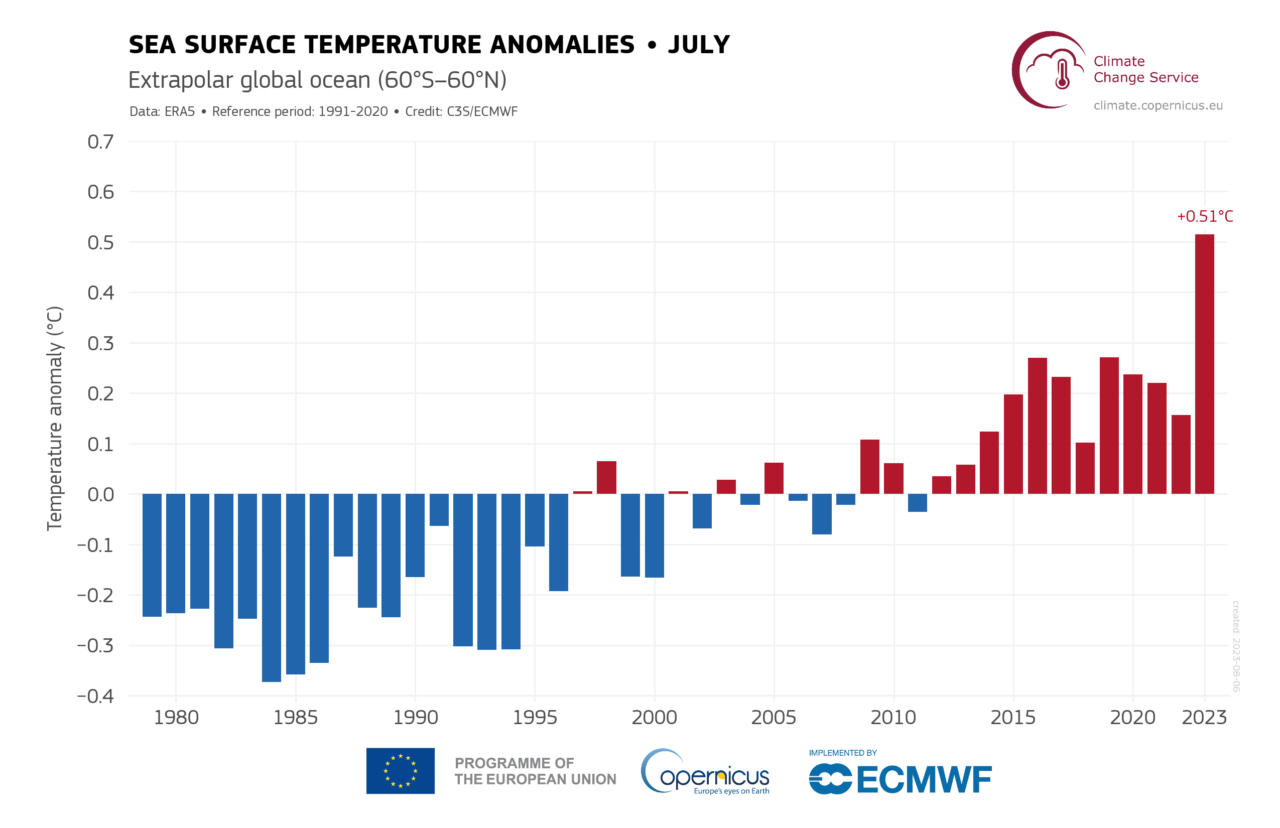

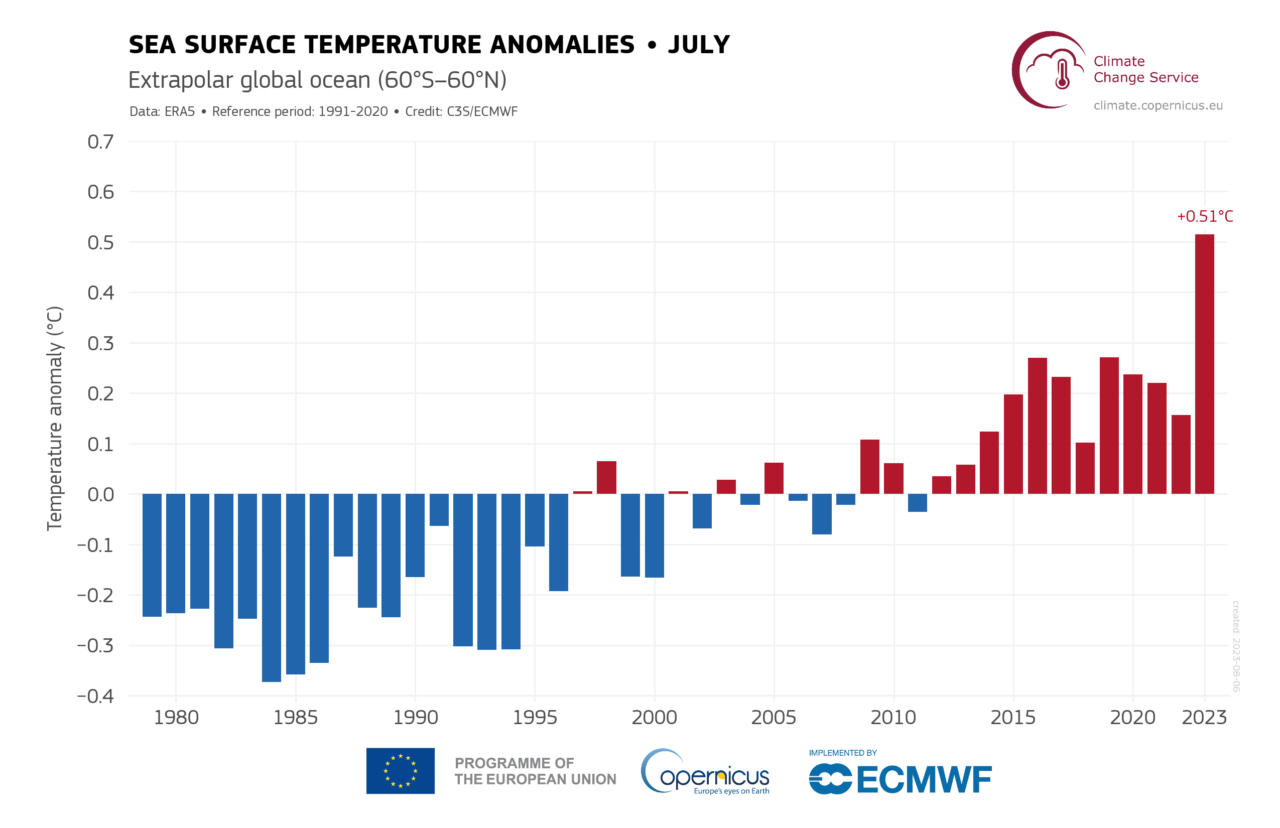

Heatwaves are affecting Greek waters, with 30 degree temperatures killing off farmed mussels growing in the Thermaic Gulf.

Last year, local seafood farmers reported a 90 percent drop in their seasonal mussel catch and expressed worry that this could become a regular occurrence.

The last serious heatwave had taken place in 2021, but scientists had wrongly predicted it wouldn’t happen for another decade.

Many fisherman have already announced that mussels will be off the menu during 2025 in regions where ocean temperatures have spiked.

But my favourite’s Gouda!

The Netherlands is a low-lying land, with sea dams holding back water that is just waiting to surge and swallow up land as ocean temperatures rise.

Gouda – a popular Dutch cheese which gets its name from where it’s made – is at risk of disappearing if the city of Gouda floods.

Experts believe that Gouda will likely disappear within the next century, stating, ‘If the land turns into water and the cows disappear, cheese will have to come from the eastern part of the country, and it won’t be Gouda anymore.’

The method can be replicated in a different part of the Netherlands, but will the cheese will have to be named differently.

Chickpeas, please?

Chickpeas are creamy, protein packed, and extremely versatile. They bolster salads, are a staple in most Middle Eastern meals, and serve as a base in tasty dal.

But in Turkey, the world’s second largest chickpea exporter after India, farmers are reporting much lower crop yields this year due to harsh climate conditions.

Scientists say that drought is the biggest threat to the ingredient, estimating that global chickpea crops will drop by 50 percent due to climate change.

Chickpeas are especially vulnerable as they lost their genetic diversity over 10,000 years ago when humans began selectively breeding the plant species to farm it.

Today’s chickpea plants are less resitant to extreme weather events, making them fragile in the face of a warmer world.

It’s not all doom and gloom, though…

Although the thought of losing these culinary delights may be upsetting, we may be able to keep these ingredients alive by changing our way of farming.

Champagne is, of course, a great example of this.

As grapes in the Champagne region of France now struggle to survive due to a shifting climate, the south of England is becoming an ideal place to grow grapes for this variety of fizzy wine. The drink just won’t be able to be named Champagne.

A similar situation is unfolding in the US, which is now overtaking Irans as the world’s leading supplier of pistachio nuts. Since pistachios are pollinated by wind, the crop is especially resilient as it doesn’t rely on endemic animal or insect species.

These types of examples bring hope, as we may be able to shift where we plant certain crops to keep them alive.

It’s clear then, that a warmer world will not just change the way we live, but the way we farm, trade, and eat.