If they can grope the president, what hope do the rest of us have?

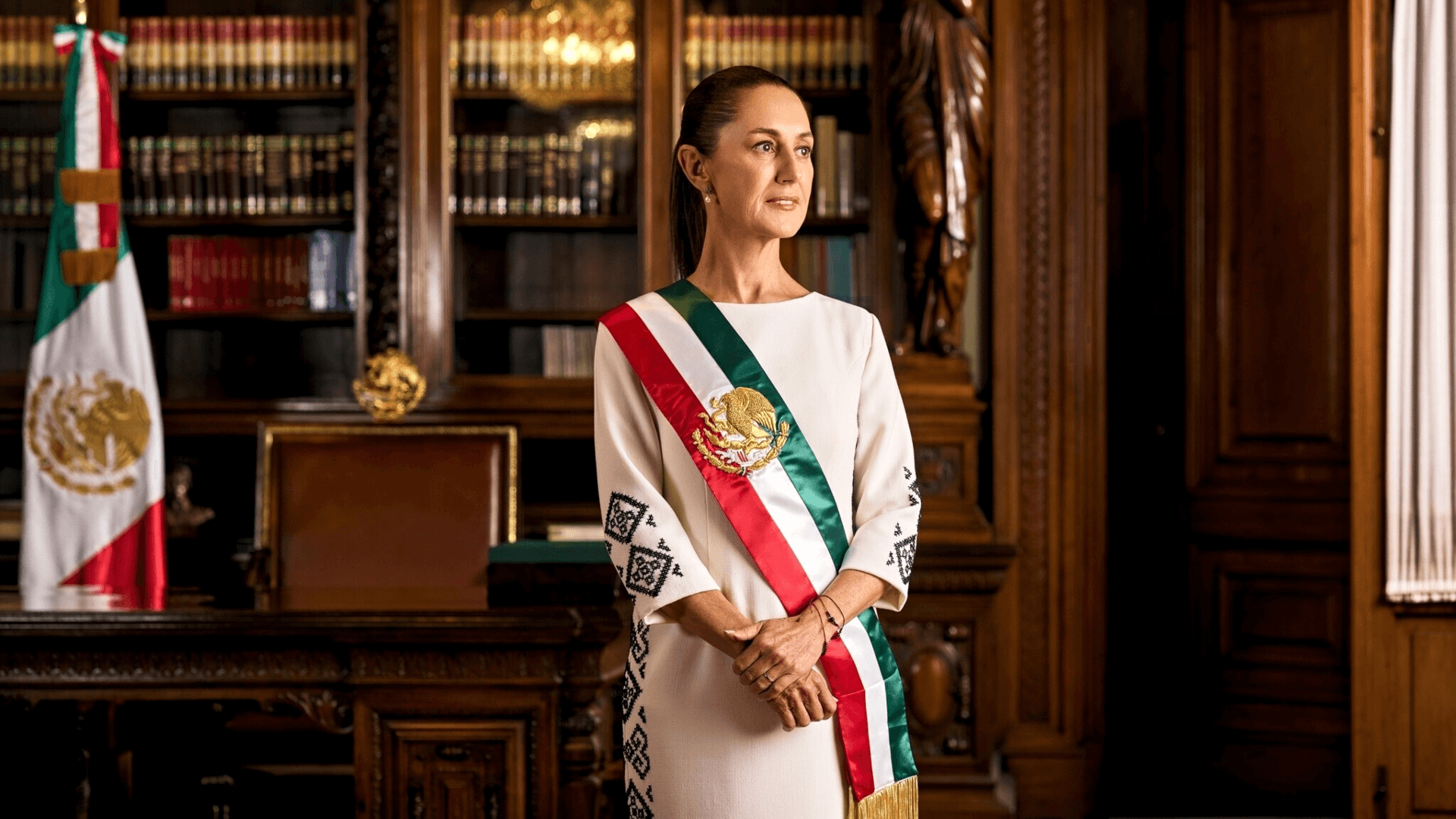

The groping of Mexico’s Claudia Sheinbaum by a drunken man has sparked outrage among women, many of whom saw their own fears and experiences reflected in her plight.

But a tepid and partisan domestic reaction to the sexual assault reveals how normalised gender violence has become in the country and around the world.

‘If the president suffered assault with that level of protection and those guards, it means that all of us women can be assaulted at any moment,’ said Patricia Reyes, a 20-year-old student.

The incident took place on 4 November while Sheinbaum was walking through a crowd in Mexico City. A man approached her from behind, put his arm around her shoulder, attempted to kiss her neck, and touched her chest before she pushed him away.

Sheinbaum remained composed, continuing to greet supporters as an aide stepped in. The man was later detained, and the president announced that she would press charges, describing the assault as symptomatic of what millions of Mexican women face daily. ‘If they do this to the president,’ she said pointedly, ‘what happens to all the other women in the country?’

Her decision to go public – and to pursue legal action – was bold. But the reaction has proved that even when the victim is the most powerful woman in Mexico, credibility and sympathy are not guaranteed.

Some opposition figures suggested the assault might have been staged, a claim that feminist campaigners quickly condemned as victim-blaming and politically cynical. Others questioned why it should dominate national debate at all, dismissing it as a distraction from ‘real issues’ like cartel violence or inflation.

Within Mexico, the incident was also largely framed as a failure by Sheinbaum’s security, which allowed a man to touch the president just days after the high-profile assassination of Carlos Manzo, mayor of Michoacán.

It’s quickly become clear that even when the victim is someone as prominent and influential as Sheinbaum, sexual violence somehow becomes a secondary topic.

This fractured response shouldn’t really be all that disturbing given its familiarity. But that’s precisely what makes it so insidious. In Mexico alone, a woman is killed every day in acts of femicide, and yet outrage only rarely translates into structural change.