‘If you could go back’ must be one of the most uttered phrases in human history. Decades before the term ‘climate crisis’ dominated tabloids and political discourse, here’s the vital 1977 memo that could have helped to prevent it all.

// This article is entirely based on research conducted by The Guardian – Emma Pattee is the author of the original story. See for reference. //

If you don’t lay in bed at gone midnight and run through a top 10 of things you could have done differently, are you even human?

Regrets are a natural part of life. We can either let them eat us up, or chalk our cringe inducing misgivings up to valuable life lessons that will serve us well in the future.

Some decisions we (I’m talking humanity in general now) make, however, have implications that can alter greater events beyond our own lives. You’ve no doubt heard of the butterfly effect, right? Well, what we’re talking about here certainly falls under that category.

Back in 1977, when Star Wars first hit movie theatres and a certain Elvis Presley left us, a single-page memo arrived at the White House warning about the potential implications of an unknown phenomena called climate change.

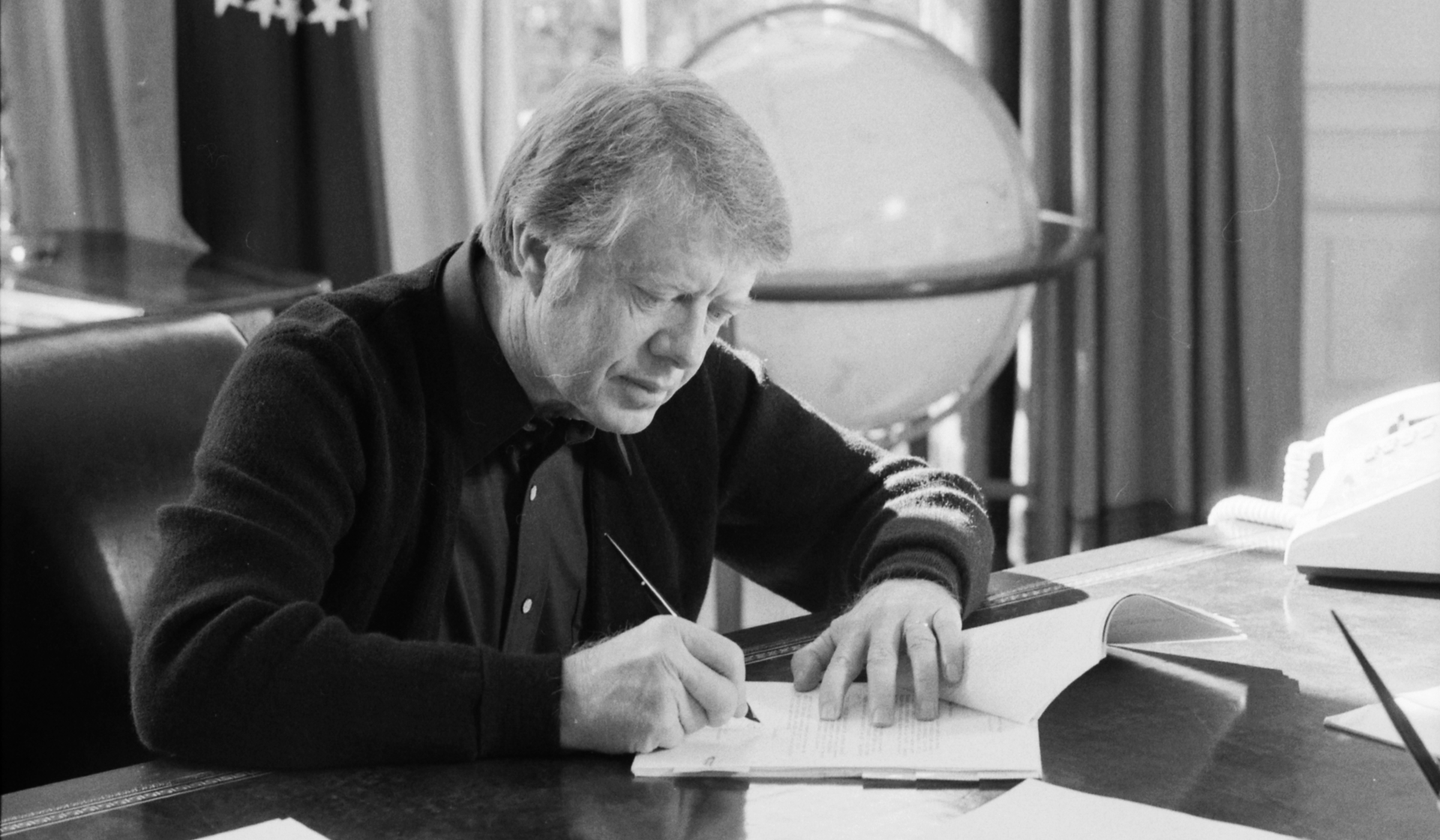

Jumping ahead 45 years, some of the assertions made within this document and delivered to US President Jimmy Carter were unnervingly accurate. You probably won’t thank me for it, but it’s time now to drudge up that pang of guilt and regret once more.

Read on for about 3 minutes and then come and join me. If only we’d listened!

The historical context

By July 1977, President Jimmy Carter had been in office for less than 12 months and yet had already built a reputation for being socially responsible and environmentally conscious.

Choosing to install solar panels on the White House caused a stir among the public at the time, but he remained firm in pushing renewables as the future of energy way before it was popular.

‘We must start to develop the new, unconventional sources of energy we will rely on in the next century,’ he famously stated in an address to the nation.

The climate memo appeared on his desk just days after Independence Day celebrations on July 4, courtesy of his respected science advisor Frank Press. It ominously read: ‘Release of Fossil CO2 and the Possibility of a Catastrophic Climate Change.’

Before being taken under the wing of Carter, Press had been director of the Seismology Lab at the California Institute of Technology and had been consulted from federal agencies including NASA and the Navy. Suffice to say – and as his colleagues publicly declared – he was ‘brilliant.’

He began the memo by explaining the science of climate change, as we knew it before we really knew it.