For the first time ever, researchers have tested the absorption of pads and tampons using actual human blood instead of water or saline solution. As it turns out, many of them are mislabelled according to their capacity for preventing leaks.

It’s inherently clear that women find it much harder than men to have their bodies understood within the medical sphere.

Continually dismissed by male and female physicians (I speak from personal experience), the gender health gap is a prevalent issue that sees us taken less seriously by professionals, particularly in the field of female-specific illnesses such as endometriosis, perimenopause, or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

But did you know that this negligence also applies to our time of the month? Despite affecting around 800 million individuals every day, periods remain grossly under-researched.

This was most recently made apparent by Stanford University, which reported that a search for ‘menstrual blood’ on the PubMed database brought up a mere 400 results from the last few decades, while a search for ‘erectile dysfunction’ had approximately 10,000.

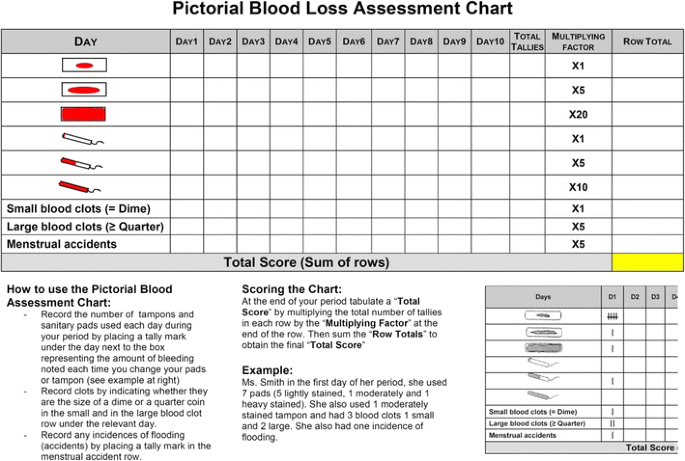

Just how far-reaching the absence of information on such a fundamental part of so many people’s lives has only this week been truly realised, however, following an investigation into the efficacy of period products.

Conducted by Dr Bethany Samuelson Bannow at Oregon Health and Science University, it was the first study of its kind in history to test the absorption of pads and tampons using actual human blood.

The aim was to help consumers make better-informed decisions about sanitary products and to help doctors assess whether heavy menstrual bleeding could be a sign of underlying health problems, such as a bleeding disorder or fibroids, or could be causing anaemia.

Until now, manufacturers have typically used water or saline solution to estimate their product’s capacity for preventing leaks, which is problematic because menstrual blood is more viscous, and contains blood cells, vaginal secretions, and endometrial tissue which, in turn, impacts how it’s absorbed.