Following news that Jamal Edwards’ death was caused by the consumption of illegal substances and that Brexit is to blame for the sharp and potentially harmful increase in fake MDMA sales, Brits are turning their attention to the government’s harm reduction efforts – or lack thereof.

When trawling through the news this morning, I came across two stories about MDMA.

The first was largely promising, an indication that the recreational drug commonly known as ecstasy could soon be approved for treating PTSD in the UK (as it already has been in the US, Canada, and Switzerland).

The second, however, raised alarm bells. Particularly on the back of Brenda Edwards’ announcement yesterday that her son Jamal’s cause of death was a substance-induced heart attack.

‘We can only hope that what has happened will encourage others to think wisely when faced with similar situations in the future,’ she wrote in a statement which has received significant praise online for raising awareness about this pressing issue.

‘It’s so important that we help drive more conversation about the unpredictability of recreational drugs and the impact they can have.’

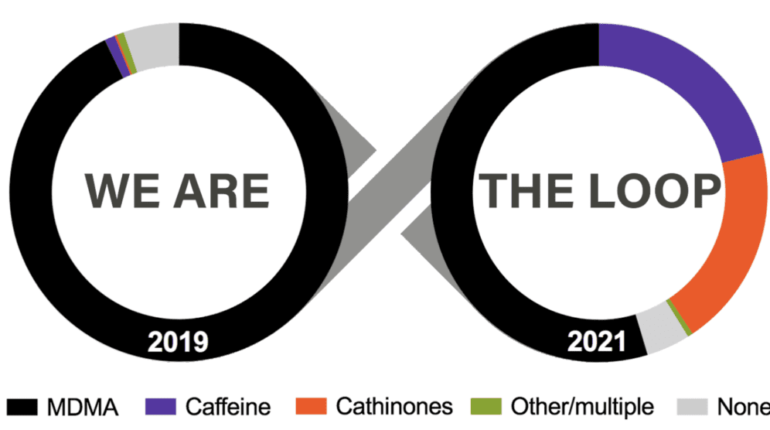

According to the Guardian, Brexit, Covid lockdowns, and police operations against supply chains have led to a sharp and potentially harmful increase in fake MDMA sales across the nation (45% compared with 7% in 2019).

As a result, festival and partygoers are now being warned of the adverse effects of these phoney pills, which include paranoia, panic attacks, psychosis nausea, and prolonged insomnia.

This, of course, is of great concern amid the unceasing popularity of recreational drugs among young people (MDMA being the most used worldwide after alcohol, cannabis, and tobacco) and reports that the number of deaths from drugs misuse is at its highest in the UK since 1993.

But why has it prompted Brits to question the government’s harm reduction efforts – or lack thereof?

Because despite the fact that MDMA is still very much a Class A drug in Great Britain – no matter how may progressions in the medical sphere we’ve witnessed as of late – and regardless of Boris’ ten year plan to ‘cut crime and save lives,’ it remains the second most commonly used stimulant in the UK.

On this note, with a substantial portion of the general population evidently continuing to take it, existing legislative strategies are doing little to curb the influx of life-threatening counterfeits.

What does seem to be instigating change, similar to the Mayor of London’s commission to decriminalise cannabis, is The Loop, a non-profit organisation that offers a free, anonymous, and non-judgemental drug checking service committed to reducing hospital admissions.