The future of Jane Goodall’s famous chimpanzees hangs in the balance, but what can we still learn from them today?

In July 1960, a twenty-six-year-old Jane Goodall decided to move into one of the smallest parks on the African continent to study a troop of chimpanzees.

Within Gombe Stream Nature Reserve, Tanzania, Goodall would live, work, and observe these animals, taking the first steps to becoming the conservation superhero she is today.

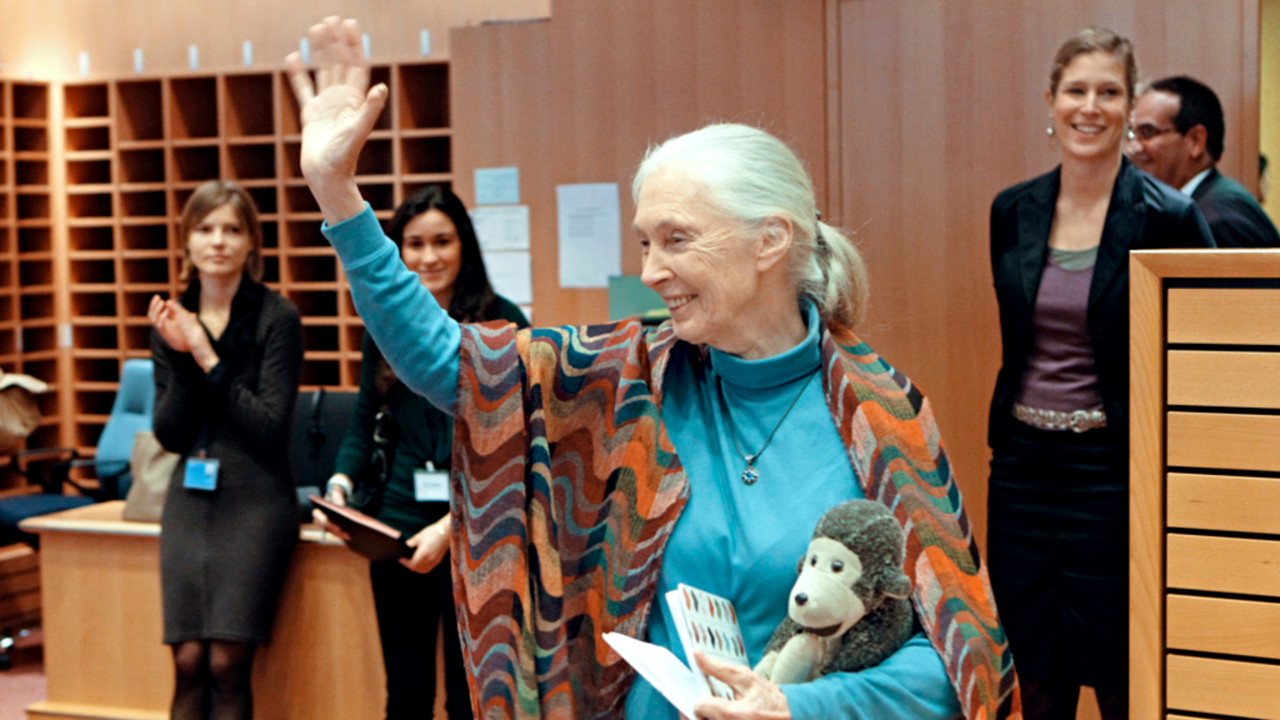

Last month, she celebrated her 90th birthday and was remembered world-wide for her immense contributions to wildlife, science, and conservation.

She is a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire and a United Nations Messenger of Peace. She has inspired movies, documentaries, books and has even recently become the main character of a children’s book in Hong Kong.

In 1977, she set up her non-profit organisation, the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI), and today, the JGI has operational offices in 30 different countries and has active programs across more than 60. It is one of the largest conservation organisations in the world.

In 2022, the JGI annual report suggested that almost 1.5 million people had contributed to or benefitted from JGI programs in Africa alone. It goes without question that Jane Goodall’s impact on the world of conservation has been truly revolutionary, but what about the chimps who started it all?

When Jane went to Tanzania in 1960, she was initially supposed to be there for a five-month research project. 64 years later, however, and the research coming from the JGI facility in Gombe Stream National Park remains at the forefront of primatology globally.

Despite the incredible success of Goodall and the JGI, the chimpanzees in this small corner of Africa – who created one of the most influential conservation empires in the world – have not had the same luck.

In the time since Goodall arrived in Tanzania, the population of Gombe’s chimpanzees has fallen from around 150, to little more than 90. Deforestation, diseases, and the increase in human contact around the park have left the future of these famous chimps hanging in the balance.

While certain protected areas and sanctuaries do exist to support these animals, such as JGI’s Tchimpounga Chimpanzee Sanctuary in the Republic of Congo, a vast majority of the continent’s primate population still exists in areas that are in close contact to human industry and settlement.

This leaves these animals at higher risk of falling victim to poaching, deforestation and communicable diseases. These challenges also highlight arguably the most important conservation hurdle that exists in Africa today – human-wildlife conflict.

While many programs such as those run by the JGI exist to protect these environments – and are slowly starting to sway governmental policy too – the reality is that the very communities within these spaces are often not consulted or are disregarded entirely by conservation efforts.