In an age obsessed with niche interests and self-optimization, community has become collateral damage.

There was a time when hobbies were simply things we did.

You ran because you liked running. We watched films because we liked them. We read books because we fancied reading books. These activities stitched meaning into the fabric of daily life. But today, there’s a relentless insistence that leisure needs to justify itself in order to be valid.

The pressure to find niche hobbies and interests against which to identify ourselves has, Mina Le argues, become an ego problem – one which ultimately feeds an ‘individualistic neoliberal culture that makes community organising so much harder.’

Le’s points highlight an intrinsic issue with modern capitalism in the age of social media – one which I’ve become increasingly aware of as someone navigating the emotional rollercoaster of late twenties-dom.

That is, society has grown remarkably good at disguising itself as individuality. We are constantly encouraged to cultivate niche interests, to set ourselves apart from the ‘mainstream,’ to become legible as interesting people through unexpected hobbies or hyper-specific tastes.

This is sold to us as freedom – an escape from mass culture. But the paradox is that our interests have never been more standardised or surveilled. They are constantly being marketed to us and then folded back into the capitalist machine.

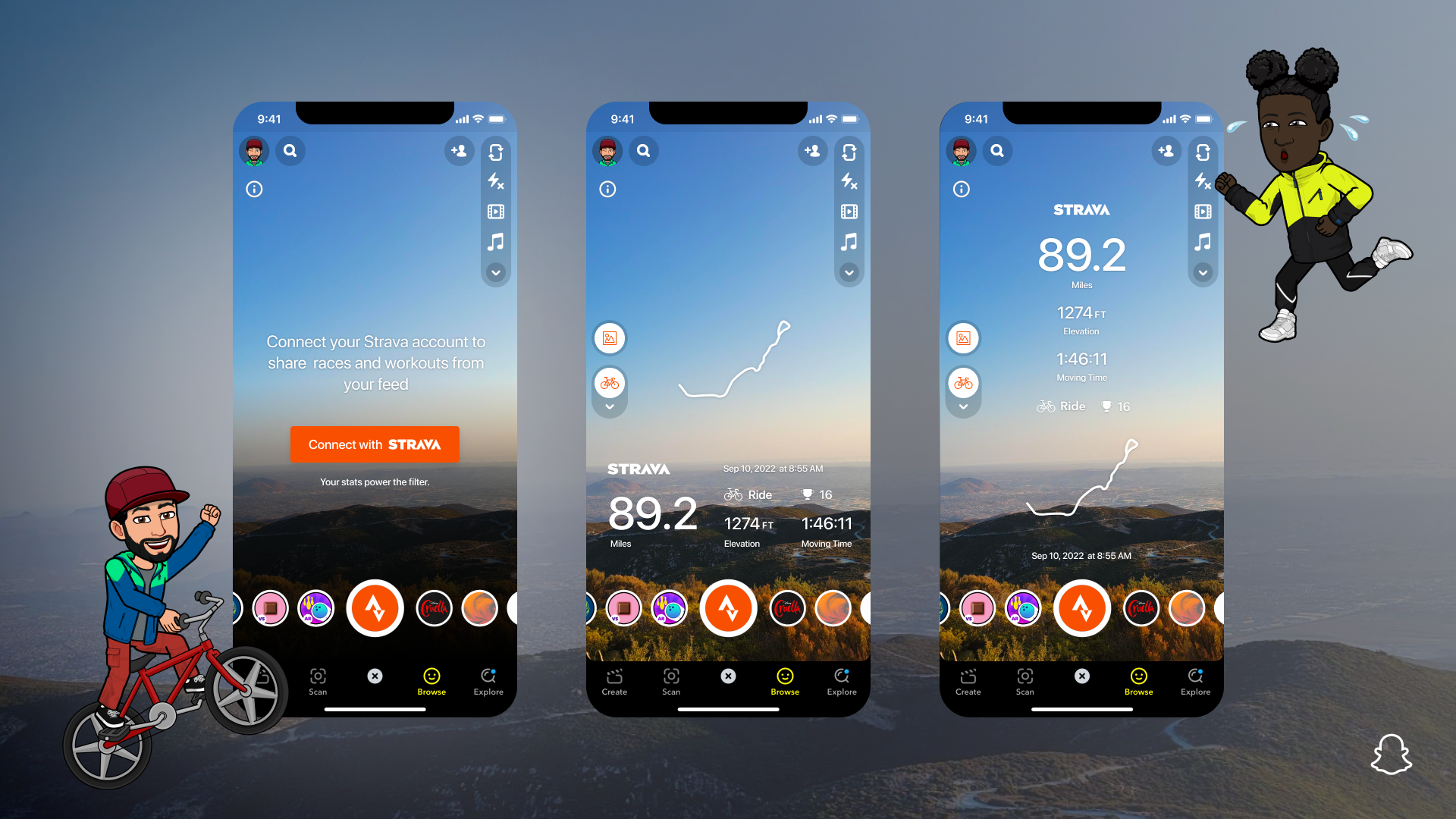

Just look at tracking apps. An entire industry has emerged to help us monitor our leisure time in the same way we might track progress at work. Platforms like Strava, Letterboxd and Goodreads have become social media phenomena, reframing our free time as performance and, often, a way to make money. There are thousands of influencers who’ve built public profiles off the back of their activity on these apps.

It’s no longer enough to do something – you must do it right. Or differently. Or better than last time. And ideally publicly.

This isn’t accidental. Capitalism thrives on individualism, and nothing fractures collective identity quite like the pressure to be singular. When we’re encouraged to define ourselves by increasingly niche interests, we’re also encouraged to see ourselves as separate from one another. We come to view ourselves not as members of a shared public, and as isolated micro-projects.

Community, by contrast, is often messy and inefficient (at least in capitalist terms). It’s harder to monetise a group of people taking part in something collectively simply for the joy of doing it.

And social media accelerates this fragmentation. The spaces designed to draw us together are pulling us apart, which is an irony we’re now well aware of.

But it’s also interesting that in trying so hard to be different, we all begin to look the same, performing versions of uniqueness that are algorithmically favoured and commercially viable.

When identity is shaped mainly through consumption and self-curation, shared obligation starts to look like a constraint. We are encouraged to treat one another less as collaborators and more as rivals, each trying to stand out in an increasingly crowded economy of personality.