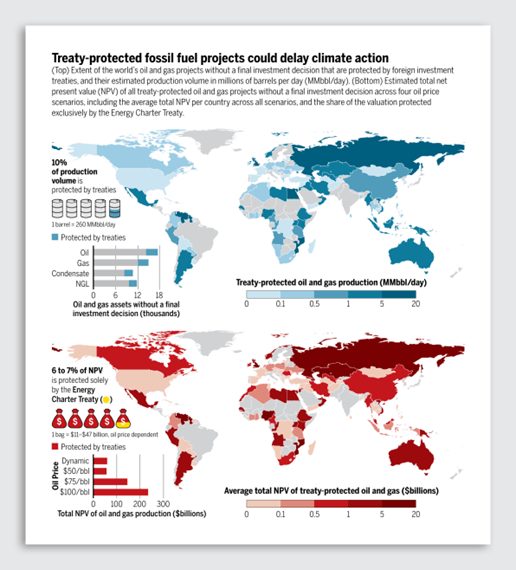

In response to attempts to limit further extraction, foreign oil and gas companies continue to file lawsuits against governments.

According to a report by the UK-based social justice organisation Global Justice Now, five major fossil fuel companies, including Rockhopper, TC Energy and Uniper, have filed lawsuits worth over 15 billion EUR in Europe and the United States.

An increasingly visible climate emergency and calls on governments to take action have led some countries to pass legislation to enable a clean energy transition – a critical step in solving the climate crisis.

Doing so, however, has reportedly led coal, oil and gas companies to incur damages and lose out on potential profits, according to the companies in question.

These lawsuits have followed bans on offshore drilling, plans to phase out coal, the cancellation of the XL oil pipeline project and requirements to report on the environmental impacts of extraction and production.

In 2014, the UK company, Rockhopper Exploration, bought a license to drill for oil off Italy’s coast, only to be faced with a ban on coastal oil and gas projects two years later. Rockhopper has since filed suit against Italy, claiming damages of over 250 million EUR – the expected future profits from the oilfield.

Ascent Resources, an American oil and gas company, is suing Slovenia because the country’s environment agency requested an environmental assessment of a fracking project which opponents claimed could pollute critical water sources.

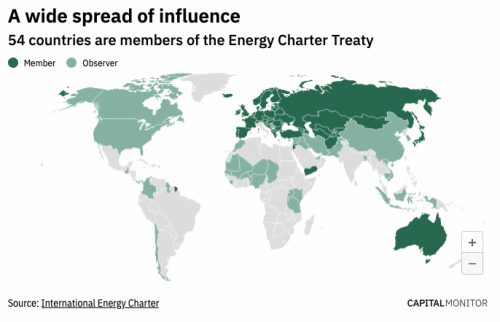

Similar cases have sprung up across Asia, Europe, North America and South America, sparking global outrage and leaving many to question what gives companies the right to challenge a government over a regulation that is in the public interest.