The European Union has agreed on a coronavirus recovery stimulus plan that shows miraculous cooperation, but it comes with some important concessions.

After an intense five days of reportedly heated debate, the EU has unanimously passed a deal to aid the recovery of its member’s economies post-COVID. The agreement includes a host of ‘firsts’ in the field of international relations, including collective debt, that may provide a new benchmark for allied nations working together. However, it includes some worrying compromises regarding environmental legislation, and rule of law.

Deal!

— Charles Michel (@eucopresident) July 21, 2020

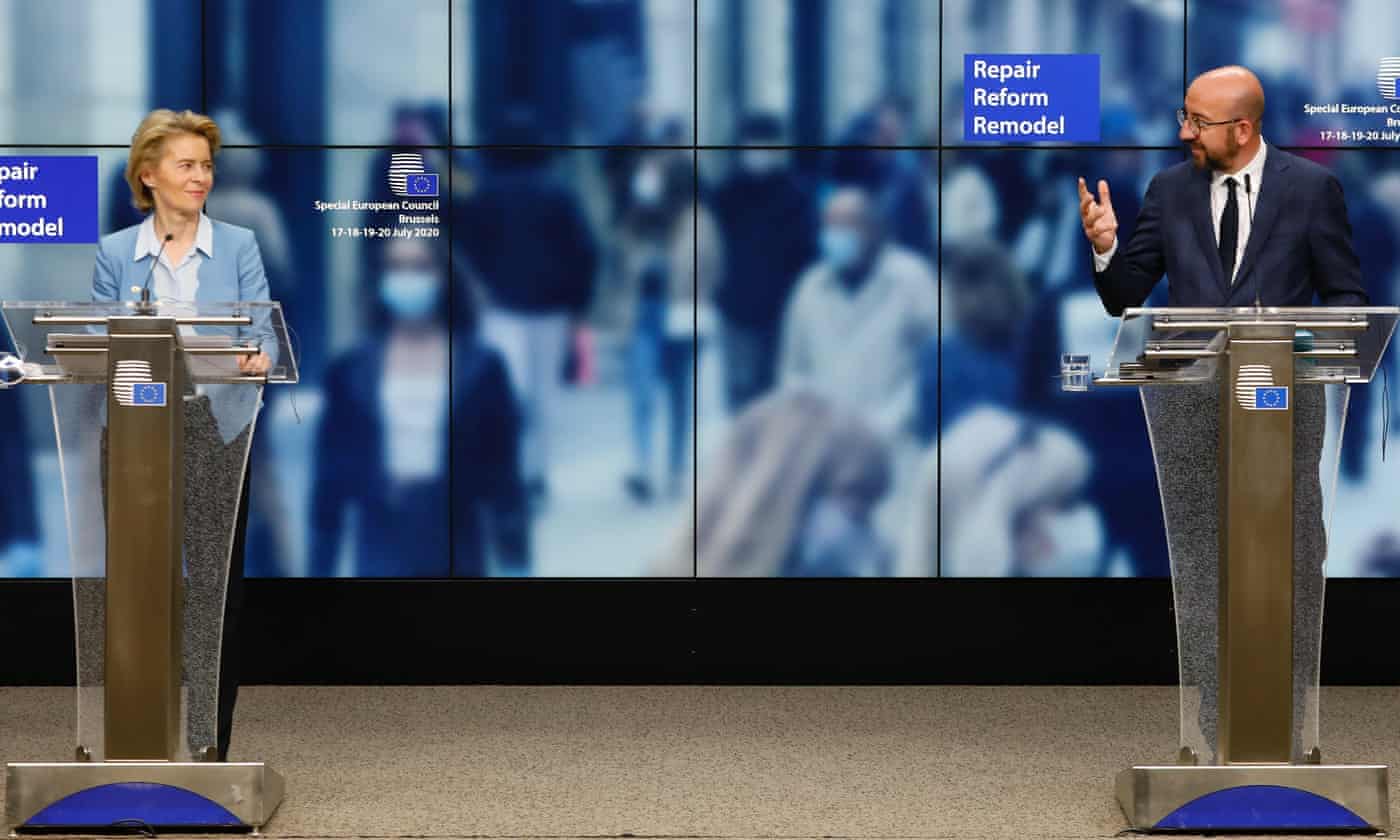

The deal was merrily announced by President of the European Council Charles Michel on Twitter yesterday at 4:31AM. ‘Deal!’ – a quick, simply declaration to summarise a complex agreement arduously reached.

Leaders from the EU’s 27 member nations gathered in Brussels for their first meeting-in-the-flesh since the pandemic – a gathering that would turn out to be its longest in 20 years. The agreement will see €750 billion pumped into the EU economy that, along with internal stimulus plans set up by each sovereign government, will hopefully keep the bloc afloat during the aftershocks of the pandemic.

The deal involves member nations borrowing money collectively, some of which will be given to struggling EU states as grants. It’s a prospect that would have seemed unthinkable just a year ago, and likely still made the toes of many northern European diplomats curl in horror; but these are unprecedented times.

EU head Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron, who led the negotiations, initially suggested a package that earmarked €500b of the €700b for grants. This was eventually watered down to €390b, with €360b handed out as loans.

The geopolitical dynamics at play pitted economically shaky southern states Italy and Spain, which have been particularly hard hit by the coronavirus, against the ‘frugal four’ Austria, Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands, who were reluctant to give out money hand over fist.

The Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte, who has a fiscally conservative government to report to, was a notably stalwart objector towards giving governments with a history of economic irresponsibility debt-free wads. He pressed for a heavier emphasis on loans rather than grants and pushed for structural economic reform conditions attached to them in order to ensure money was productively spent.