Describing this monstrosity as a ‘patch’ has led many to believe there is a clearly defined section of plastic waste that could theoretically be removed using massive nets. That assumption is sadly misguided.

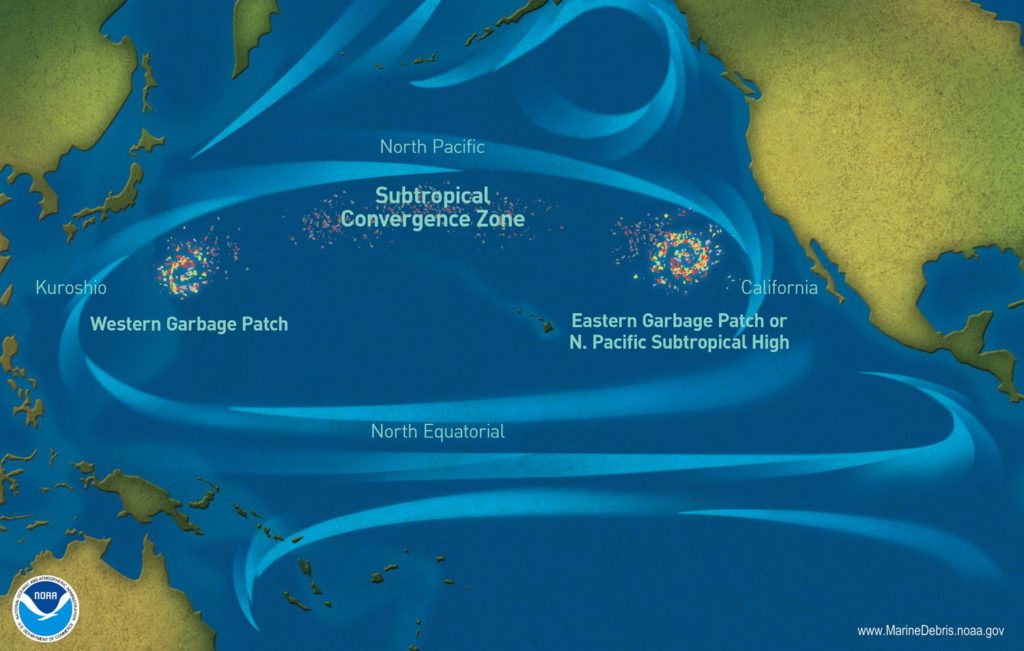

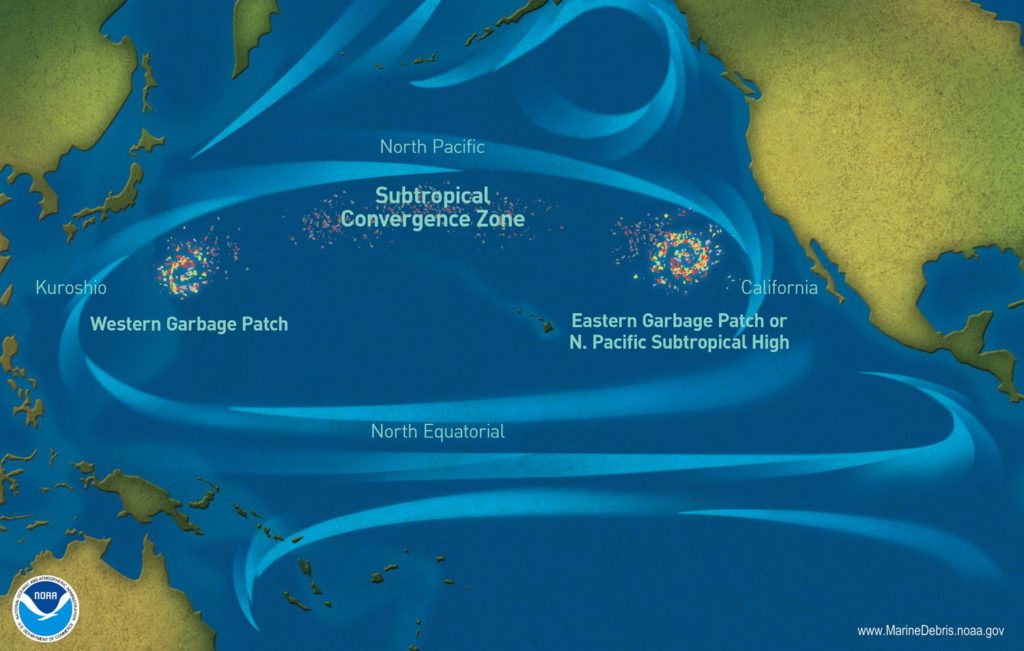

In reality, there are two masses of marine debris (located in East and West ends of the Pacific), joined by a stream of smaller bits of plastic that flow through an area called The Convergence Zone, which frankly sounds like an upcoming sci-fi thriller starring Sandra Bullock, if you ask me.

But seriously, The Convergence Zone dots the midsection of the North Pacific where warm southern waters meet cool Arctic water, creating a highway of moving debris from one gigantic patch to the other. The graphic below will provide an illustration of how it sparsely joins the plastic supply to both patches.

At the end of this route, gyres, or whirlpool currents in the west and east ends hold the plastics in one place, where they remain destined to float in the Pacific eternally – unless we take action.

What is the plastic patch made up of?

What is it not made up of, is probably the better question…

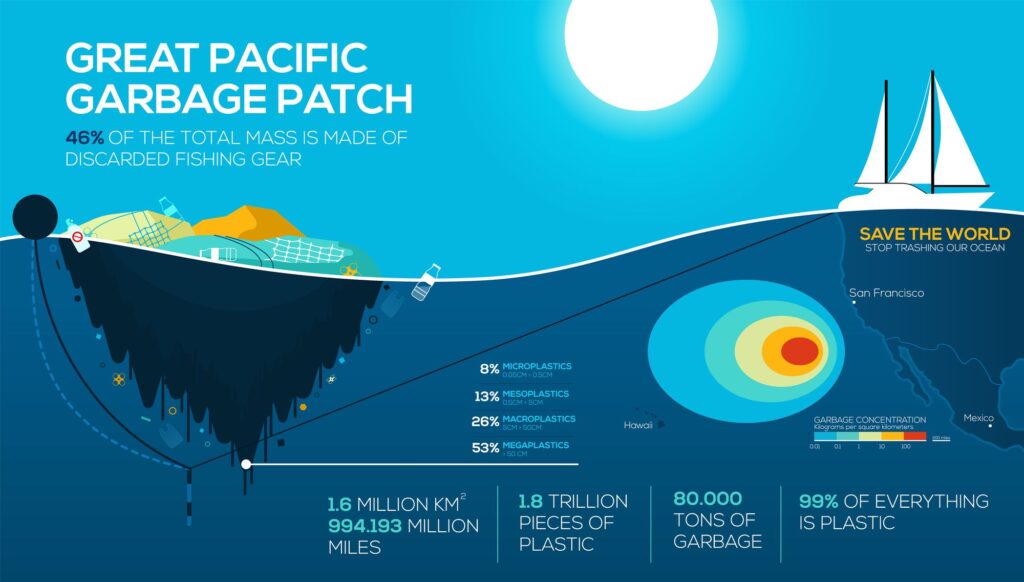

Industrial fishing equipment makes up 46 percent of total marine debris, which – to our luck – can be easily spotted and removed.

The rest is made of up plastic debris larger than five centimetres, with some as small as a grain of rice. While easy to spot in the first few years of arrival into the ocean, these eventually break down into microplastics that will never biodegrade.

From boats and satellites, both the giant patches and the Convergence Zone become elusive as a result of being made up of millions of these microplastics. At least 8 percent of the patch is comprised of them, some of which cannot be detected by the human eye.

For the most part, the GPGP just looks cloudy – like a gross, unappetising soup. And what makes the clean-up of tiny microplastics a difficult task is that they don’t just float on the surface, but also venture further into the depths.

Trawling for microplastics at deeper levels could mean that large populations of plankton and algae also get captured in the process. This has potential to cause a shortage in the base of the marine food chain, threatening the collapse of the surrounding ecosystem.

One environmental organisation called The Ocean Cleanu is using a net capture method nicknamed ‘Jenny’ to clean up the GPGP.

After two unsuccessful attempts, it has now removed 20,000 pounds of plastic from the area. The conservation group has stated that its slow-moving, specially designed net ensures that marine life has a chance to escape capture.

While this project is something to be applauded, The National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) ’s Marine Debris Program has estimated it would take a year for 67 ships to clear up one percent of the discarded fishing equipment found in the Pacific.

Arguably, the garbage took decades to get there, so the quest to remove them won’t be easy – and we really shouldn’t be discouraged by the amount of time it would take to do so.

If nets, plastic, and smaller microplastics remain in the ocean, they run the risk of tangling marine life (whales, turtles, seals, penguins, manta rays and more) by drowning or choking them to death. Not to mention, the sea provides 17 percent of our food supply, meaning we would do well to avoid plastics on our plates.

Many hands could make light work, but unfortunately, The Great Pacific Garbage Patches are distanced too far from any country’s coastline. Because of this, no nation is willing to provide funding for its clearance, making efforts like The Ocean Cleanup’s especially worthy of praise.

So… how will we fix up?

Although no country wants their reputation soiled by claiming the mess – like when dishes pile up by the sink and all four of your housemates are reluctant to tackle it alone, making the situation worse – the responsibility of clearing up should be shared globally.

With about 90 percent of plastics not properly recycled and most taking upward of 500 years to decompose, it’s likely that packaging, fishing gear, and other plastic materials found in the Pacific cannot be traced to any specific country in the world.

Despite the stubbornness of nations to own up, other amazing initiatives are taking place around the world to rid our oceans of plastic where possible, with some inspired by ocean life itself.

We’ve already featured one of them, the Manta, which is due to set sail within the next few years. Meanwhile, official environmental concerns about the health of our oceans are reaching a paramount.

This year’s UN Ocean Conference was jumpstarted last year by innovation and research teams who are investigating ways marine-based companies can change their behaviours to help re-establish a balance within underwater ecosystems.

The best we citizens can do at the moment is challenge ourselves to make sure as little plastic ends up in the ocean in the future – by avoiding it as often as possible. For tips on getting one step closer to eliminating plastic from your everyday routine, check out our recently published guide here.