Today, one third of Brits say they adhere to best-before dates while shopping or rummaging through their refrigerator – as if these stamps seal an item’s destiny to commence decomposition at the stroke of midnight, Cinderella-style.

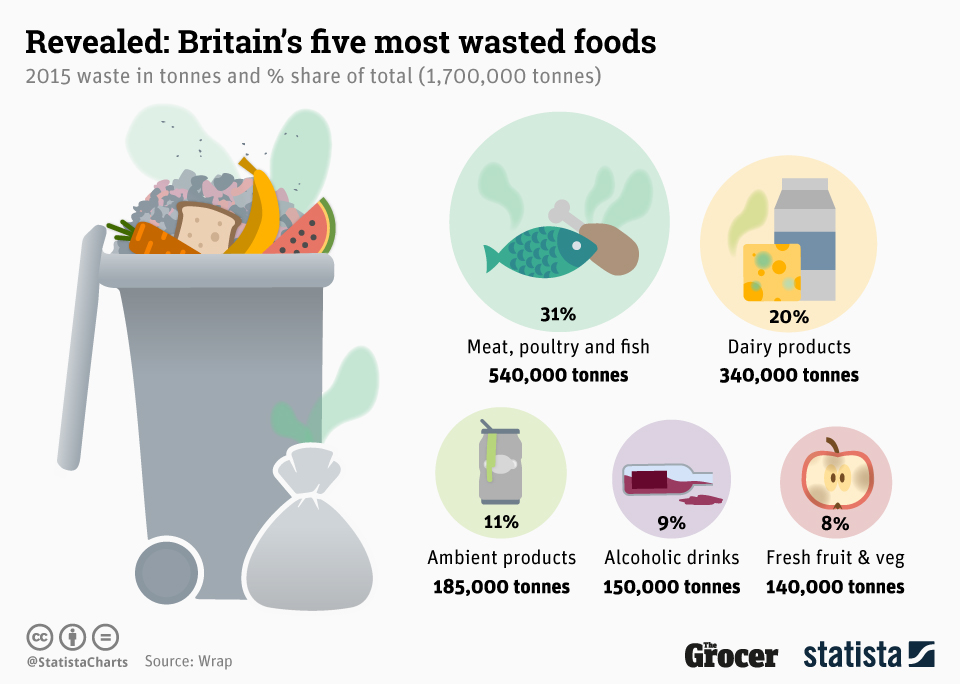

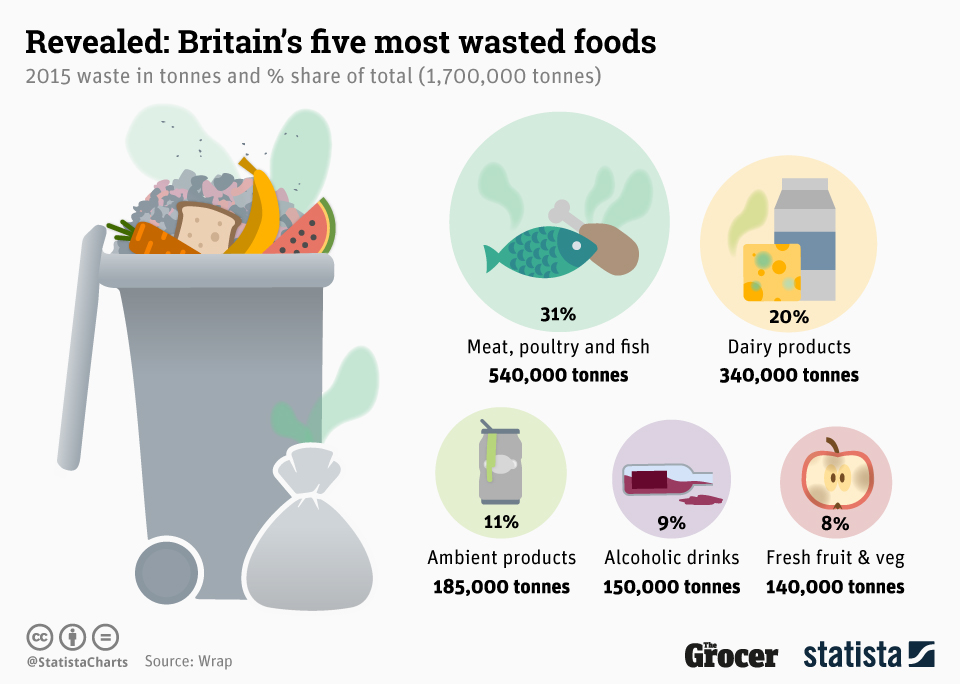

Whether people are worried about food-borne illnesses (i.e.. Listeria) and digestive sensitivities (shoutout to the IBS crew) or simply playing it safe, many food critics say best-before dates have become a major driver of the global food waste crisis, which saw an excess of 900 million tons of food thrown out in 2021.

Critics further suspect that best-before labels were made up by retailers to urge consumers to throw out ‘old’ goods and buy more, sooner. The Guardian suggested in 2009 that such labels are attempts to avoid health and safety lawsuits from ‘the same people who need a CAUTION: CONTENTS HOT label on takeaway coffees.’ Ha!

As mentioned, legally enforced guidance on food freshness is a relatively modern practice. Before humans had less free time to think for themselves and fewer computers to churn out numbered labels, society used its common sense(s).

Looking at a vegetable and gauging whether something’s off only takes a few seconds, and if it’s too far gone, well, you’ll definitely smell it. So why do one third of shoppers not trust themselves to do either? Big news, gang: it looks like we’ll soon have to.

Waitrose has announced it will ditch best-before dates on 500 of its fresh products, effective from September. The retailer’s sustainability and ethics director expressed her hope that, by leaving the judgement of freshness to the customer, perfectly fine produce like apples and potatoes won’t be wasted as frequently.

Marks and Spencer’s, the first to introduce best-before dates to Brits in the 70s, has also announced best-before label removals on over 300 products, with Tesco and Co-op following suit, removing dated labels on 100 fresh products in-store.

For those who refer to best-before dates as an extension of their ethical code of practices, there’s key information about what these labels signify that might pacify your anxieties.

Best before dates are exactly that. They simply stand to indicate at which point an item will continue to retain its optimal freshness, not when it will cease to be nutritionally safe to eat, which is what ‘use by’ labels are for.

For goods like milk, eggs, and meat, ‘use/sell by’ labels will still be placed on outer packaging. As someone who has accidentally eaten an out-of-date egg and spent an entire night trying not to move in bed at risk of chundering all over myself, I’m also grateful for this knowledge.

The moral of the story is that best before dates aren’t the be all and end all of food freshness, and a widespread move to ditch the things (Norway and Denmark are joining in, too) proves citizens have enough sense(s) to know what’s good.

Though some may still be lacking in their sense of smell and taste due to a battle with the VID (and I extend my condolences, really) the wide majority will be more than capable of gauging whether that bell pepper is a little too wrinkly or that two-week-old tangerine is on its last days.

In the end, cutting down on food waste will not only ease increasing pressure on the agriculture industry, but it’ll also help slow climate change as a result of less methane in the atmosphere released by organic matter’s breakdown.

If the planet is the least of your worries (what are you even doing here?!) you might be swayed from your opposition to label removal by the reminder that it might just save us some of our hard-earned cash.

And with the number of inflation-dominated headlines splashed across news pages right now, can you really argue with that?