Economic indicators have fallen out of step with our lived values, and according to a recent poll the UK has noticed.

This week the UK’s latest GDP figures will be published, covering the period from January to the end of March. GDP is calculated by taking the sum total of a nation’s spending, investment, and trade balance (imports minus exports) then representing this as a single number. Essentially, it shows the aggregated wealth of a nation’s population.

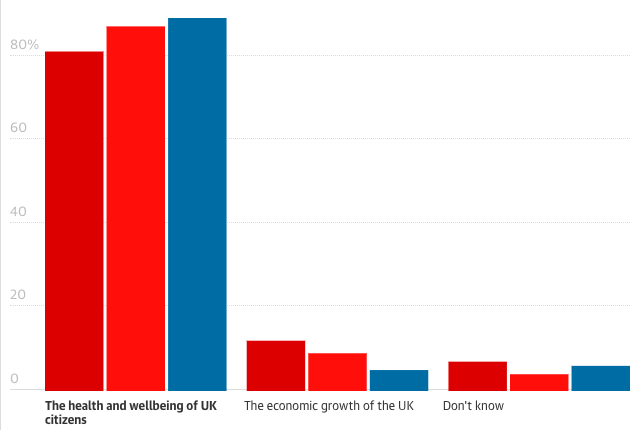

The numbers in the upcoming report are, for obvious reasons, expected to show a dramatic fall. The initial impact of COVID-19 and lockdown measures have left a huge dent in the economy, in the UK as in the rest of the world. But a recent poll by YouGov urges policymakers not to put too much emphasis on the figures. According to their research and this Guardian report, eight out of ten people in the UK would actually prefer the government prioritise health and wellbeing indicators over economic growth, for the lockdown period and beyond.

For those who’ve been paying attention to the interaction between an increasingly nationalist population and the staunchly technocratic government aids who create GDP reports, these findings come as no surprise. The vision of a nation’s economic growth on aggregate as the principle and natural vehicle of collective progress no longer necessary holds.

The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted this: whilst businesses shutting down has affected the economy negatively, some measures of quality of life, such as air pollution and the natural environment, have actually improved, though this won’t be reflected in the government report.

The public no longer see GDP as reflecting their lived reality to the same extent they once did. Statistics were born at a time when the modern nation state was becoming established as the ultimate and unchallengeable unit of political geography, but globalisation and digital technology has disrupted that assumption. The concentration of power and money in urban centres, along with other factors of rising income inequality, has meant that the average no longer reflects the mean.

By way of example, Britain’s economy is the fifth largest in the world, and yet the majority of regions experience GDP per capita below the European average. The kingdom claims its stellar GDP almost solely through the output of London, where income per head is eight times higher than it is in the Welsh valleys. Beyond the perimeters of prosperous metropolitan cities, unemployment can easily rise along with the nation’s GDP, and frequently does.