How the feel-good stories the media is feeding you actually expose the deepest flaws in our society.

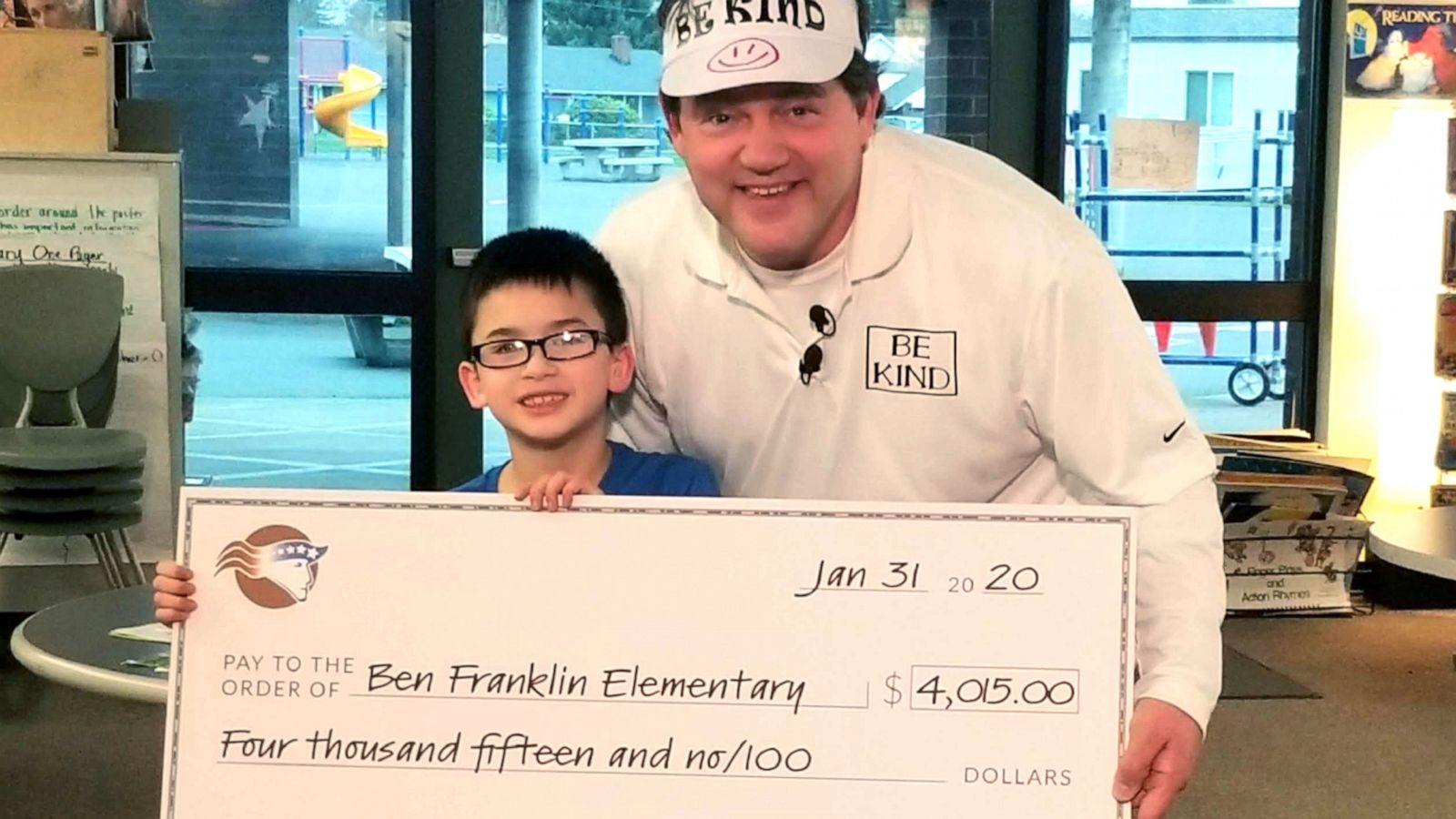

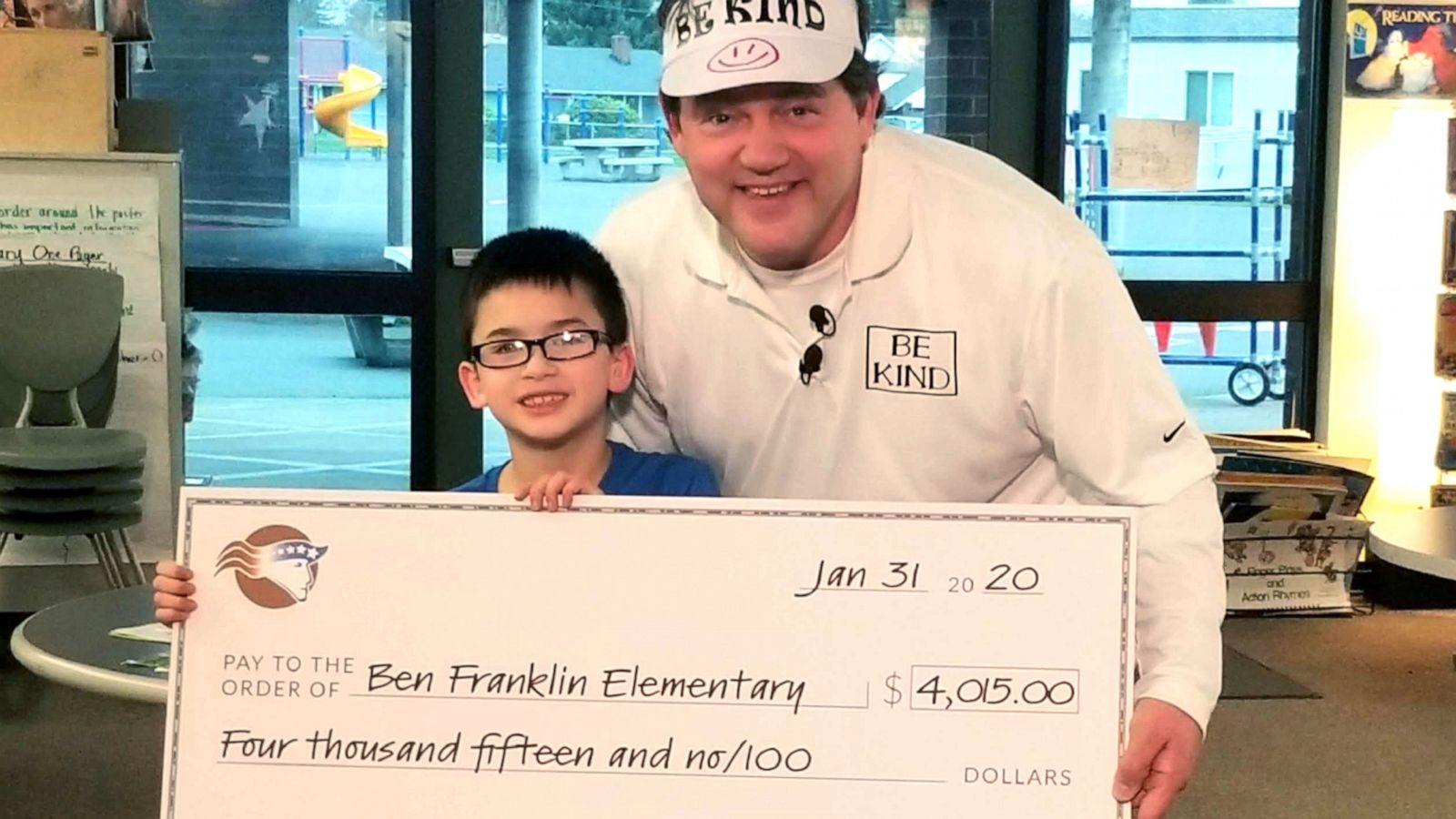

In January this year, a young boy from Vancouver, Washington sold keychains in order to pay off his peers’ lunch debts. The story hit international news. 8-year-old Keoni Ching, spurred on by the spirit of his primary school’s ‘Kindness Week’, sold the bespoke items for $5 a pop in what quickly became a national phenomenon. As CNN put it ‘Once word of Keoni’s key chains and his heartwarming cause got out, people from all over the country started sending in their requests for one of the custom key chains’. Ultimately, Keoni was able to raise $4015 through the exaltation of a few warmed hearts from affluent homes – or the equivalent of almost 3 months’ work on US minimum wage. Now his peers and their families will not be billed for outstanding food debts.

‘Feel-good’ stories like this frequently metastasise in the cockles of the internet’s heart through various publications, interested in telling us about the homeless man in California who recently landed a job through handing out resumes on a highway in 35-degree heat, or the successful GoFundMe that allowed a leukaemia patient to pay his medical bills, or the dad who worked three jobs to buy his daughter a prom dress, or the university student who ran 20 miles to work after his car broke down and was subsequently given a new sedan by his boss. These tales of fortitude despite overwhelming odds are always handed down to us with the same mawkish, forced grin we’re expected to wear when we receive them.

And what’s more, many people do lap these stories up: like J Alfred Prufrock’s urban anaesthetic, or perhaps more accurately like Marx’s opiate. They’re ostensibly designed to remind us of the resilience of the human condition, and the potential boon of a system predicated on human generosity. These stories shout ‘Look over here at this shiny act of kindness, bravery, and fortitude!’ And presenting in such a sickly-sweet package, how can we help but look? But whilst we stare slack-jawed and smiling at the feel-good human-interest stories, we’re prevented from looking the other way and seeing the systematic failures that made such kindness, bravery, and fortitude necessary.

Nowadays, our notion of what constitutes a tale of heartwarming embattlement and what constitutes unnecessary and systematically enforced embattlement has been upended. Rather than being life affirming, stories like this should fill us with icy fear. Blogger and technologist Anil Dash said it best when he Tweeted:

‘Most of what gets shared as heartwarming stories are usually temporary, small-scale responses to systematic failures. I wish we found it just as inspirational to make structural changes to unjust systems.’

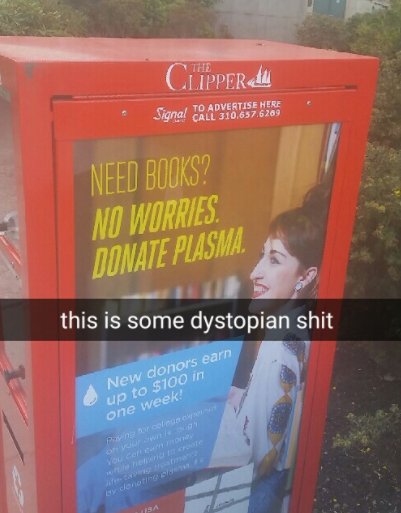

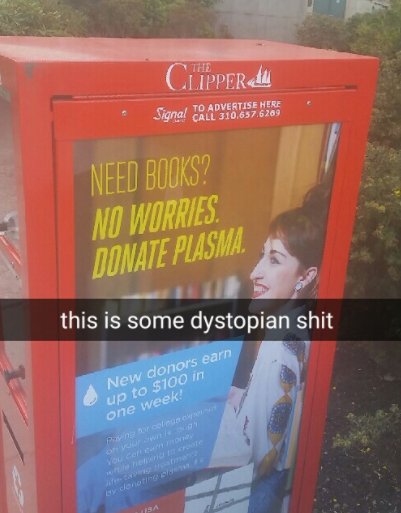

And it’s in the small systematic eroding of our personal freedoms that we can find companies spotlighting the occasional shiny foil nuggets in a trash heap. This reality we find ourselves in is given the sobriquet ‘a boring dystopia’ by cultural theorist Mark Fisher in 2015.

The boring dystopia refers to our Dali-esque surrealist landscape bumping up uncomfortably with the metal acridness of A Handmaid’s Tale in ways that are less sensational than either. It’s the bland, mildly coercive signs that abound in late-stage capitalist society that foster a sense of isolation or unease. The small, institutional reminders that the American Dream has gnawed at our freedom and usurped our life-force in service of a society that doesn’t support us.

For a time in 2015 Fisher maintained a popular Facebook group bringing together examples of what he called ‘Silicon Valley ideology, PR and advertising… [distracting] us from our own aesthetic poverty, and the reality of what we have’. What we do have, according to Fisher, is just a bunch of ‘crappy robots’. Fisher, who spend his life as an academic and philosopher poking holes in the wallpaper of capitalism, committed suicide in 2017. His legacy was to gesture to the water we’re all swimming in.

The true insidiousness of stories like Keoni’s is that they seem to suggest that equality and prosperity can be reached through benevolence under capitalism. But, in reality, Keoni and those like him are the exceptions to the rule. What you don’t see are the hundreds of thousands of US children that will end the year still in their lunch debt due to a top-heavy economic system that punishes the already poor and enforces a parent’s financial burdens on their children.

This year, Good Morning America gleefully reported on Missouri mum Angela Hughes, whose was given by her colleagues over 80 hours of their vacation time after she failed to qualify for maternity leave. ‘Donating vacation time to new moms is a trendy – and generous – co-worker baby shower gift’ chirpily asserts the articles Twitter caption. As if to emphasise the farcical uncanniness of this corporate ghettoising, the mother on the article’s title image is not Angela Hughes, who is a black woman, but a young, white, Colgate alternative. As if we needed further evidence that articles like this are designed to project a falsified image of contentedness.

“It really, really meant a lot to me… I was extremely appreciative and very humbled.”

Donating vacation time to new moms is a trendy – and generous – co-worker baby shower gift: https://t.co/EeaQMNX425 pic.twitter.com/FWwyl6kPb6

— Good Morning America (@GMA) July 18, 2018