We’ve heard plenty about how the manosphere is radicalising young boys, but is it having as big an impact as institutions are claiming? Initially used to describe lowly incel gatherings, the term has snowballed into a loose catch-all for elements that don’t always align.

Louis Theroux has a new Netflix documentary on the way for March titled Inside The Manosphere.

Predictably, the promo includes cutaways of online personalities like Sneako, HStikkytokky, and Ed Mathews. It vindicates my own belief that a term once used to describe a fringe online subculture is becoming a convenient catch-all to classify a wide range of immature lad (or toxic bro) behaviour, regardless of intent or ideology.

While the ideas associated with the ‘manosphere’ predate the 2020s, it was around 2022 that they began to enter the public consciousness carried by social media and mainstream news. The concepts brought to light were undoubtedly grim.

Groups of incel men and teens were seen to adopt a cynical worldview that framed women as insidious or shallow, reinforced feelings of resentment, and dismissed vulnerability as pointless. In 2025, small but persistent online communities still exist that promote reductive views of gender and encourage nihilistic interpretations of romantic relationships.

Despite what the media would have you believe, these groups are largely disconnected from mainstream youth culture. So, why then are a handful of dense influencers and streamers being pushed as today’s face of the manosphere?

Until recently, the term was used to describe people who explicitly identified with a shared set of beliefs, congregated in insular online spaces, and, in a small number of documented cases, acted on those ideas in genuinely harmful ways. That specificity mattered. It allowed the problem to be named, scoped, and understood in context.

We’re now equating that to Kick streamers acting in a performative – and often deliberately provocative – manner to get attention, purely because some of the vocabulary is similar. Like many, I’m of the opinion that HStikkytokky and Ed Mathews are bellends, but to lump their cringe-inducing follies in with incels out of sheer inertia feels massively unjustified.

Seeing young lads swanning around Marbella arrogantly asking girls for their Snap isn’t comparable to coordinated ideological conditioning. Immaturity alone doesn’t signal some deeper underlying kinship, even if the language used is sometimes rough and uncalled for.

More importantly, in terms of motivation, the two are almost opposites. Incel communities are withdrawn and insular, resigned to dwelling in resentment and fatalism. By contrast, the influencers now grouped alongside them depend on being conspicuously extroverted, selling aspiration, visibility, and the promise of wealth and sexual access.

The latter’s audience, whether there intentionally or pulled in by algorithms, are a broad and casual mix, the vast majority consuming this content as entertainment and viewing it as ‘rage bait’ rather than instruction.

Yet governments and institutions often struggle to make this distinction, treating the act of encountering a clip on X as equivalent to internalising an underlying message, and implying an ever-present risk of indoctrination – as though these influencers function as entry points to incel ideology.

Much of the panic around the manosphere appears to come from people with limited familiarity with the spaces they’re attempting to interpret. Performative behaviour, particularly from streamers, is often taken at face value and read as evidence of something coordinated and dangerous, rather than what it usually is, exaggerated content designed to provoke engagement.

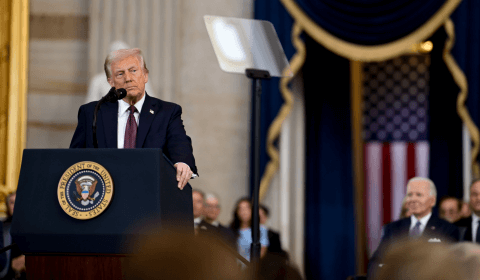

It’s why something as shallow as Netflix’s Adolescence can land with such force and leave the PM so affected. For those of us who knew about the subject going in, it barely scratched the surface of incel culture, rolling out the ‘80/20 rule’ and talk of the ‘red pill’ as basic exposition points, complete with an obvious villain.