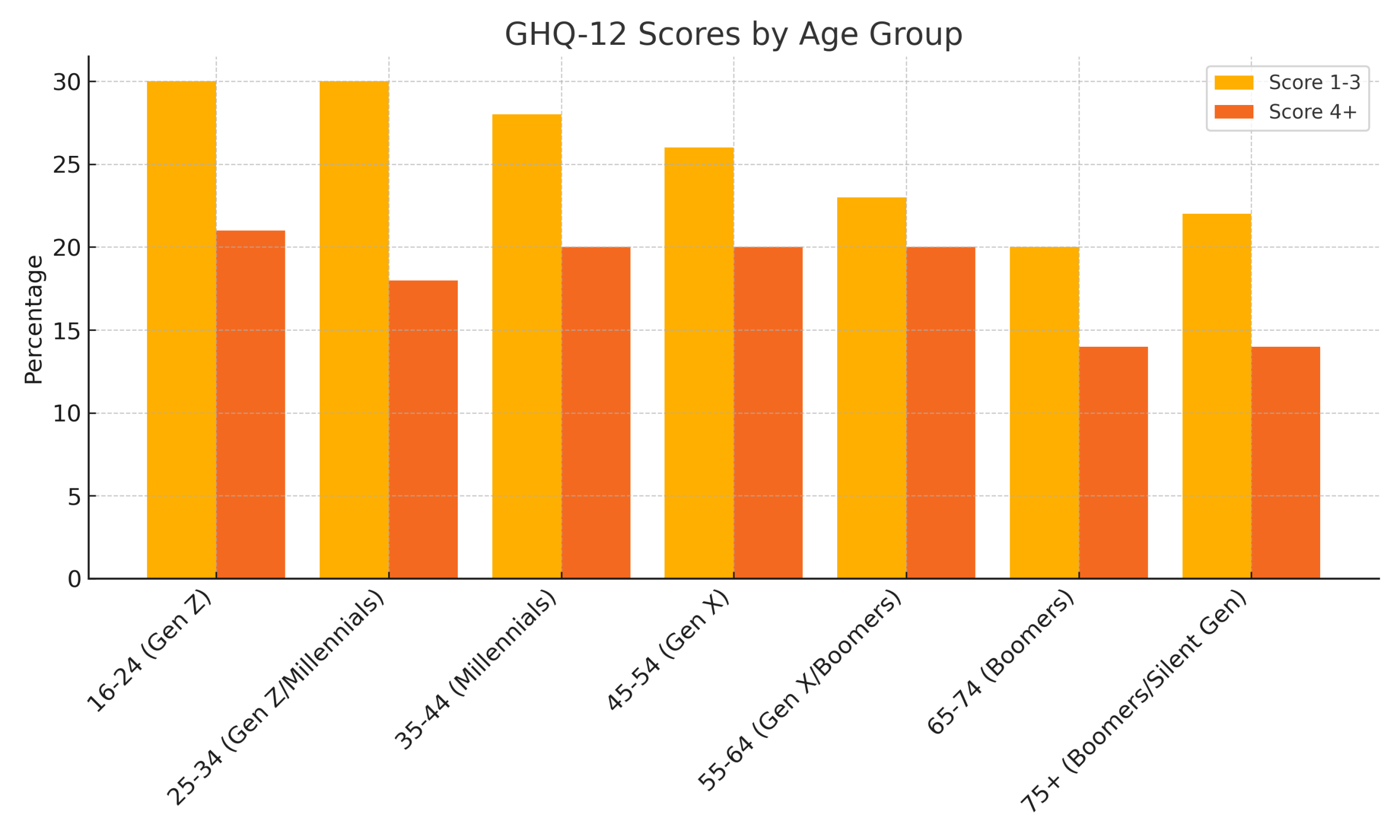

Gen Z are known for tempering harmful habits like drinking or smoking, but are they destined to age poorly anyway?

If you’re chronically online, you’ll have seen self-deprecating videos from Gen Zers talking about how they’re ageing worse than millennials, but is there any genuine credibility behind the jokes about receding hairlines? There might just be.

Experts are increasingly warning of a ‘generational health drift,’ in which future cohorts may have worse health than their predecessors did at the same age. Medical professionals, academic studies, and official health stats are all pointing to a few salient factors.

In the UK, life expectancy has risen by 30 years over the past century. Baby boomers (aged 61 to 79) born two decades after WWII have witnessed massive advancements in medicine, science, and nutrition, and they’re predicted to live longer than any generation that came before. 89% of people born in Britain in 1955 lived beyond 60, compared with 63% in 1905.

As children, the boomers were first to access the fledgling NHS and its explosion of new vaccinations and antibiotics, and in adulthood, they avoided mandatory army conscription which concluded in 1960. By this time, manual work was significantly down, university places were on the rise, and general living standards were vastly improved.

Given science deems circumstantial pot luck synonymous with a long life, surely modern living – and its boundless offering of convenience and leisure – will help young generations to thrive in old age too, no?

On the contrary, research suggests today’s living standards may be a poison chalice of sorts, and that, despite Gen Z’s obsession with wellness, they’re unlikely to live as long as their parents and grandparents. Dr Jenna Macciochi, a University of Sussex immunologists and author of Immune to Age, has spoken at length about why.

A recurring subject with Dr Macciochi is ultra-processed foods and how much generations are consuming/ have consumed in childhood and adulthood. Those in retirement today will surely be the last to pass without having ever eaten any, while the majority of those still at work or school are accustomed to consuming it weekly or even daily. There’s nothing quite like a pop tart delivered on an Uber Eats bike.

‘In postwar Britain, when food was still scarce, people actually ate better,’ Dr Macchiochi says. ‘They’d split their meals with fibre and lentils and got goodness into their diets in other ways. They didn’t have access to ultra-processed food for the majority of the start of their life.’

By contrast, today’s highly palatable and packaged supermarket grub has become so vastly normalised that younger generations aren’t readily afforded the same level of nutrition. When supermarket shelves are full of ultra-processed foods, those of us who cant afford to shop at wholefood retailers are repeatedly exposed to the health risks.

‘We’re not short of information on how to look after our health, we’re short of agency to put that information into action,’ Dr Macciochi says. ‘You can’t change it if your job is deskbound. You can’t change that you live in a food environment where you’re marketed really heavily to eat the wrong things.’