Actor Park Sung-hoon has been criticised for playing a trans woman in the latest season of Netflix’s ‘Squid Game’. But those defending his casting say the issue of on-screen trans representation is more complex and layered than we’d like to think.

Squid Game’s second season is one of the most hotly anticipated shows arriving this side of the new year. Since the trailer dropped earlier this month, fans have been avidly discussing any easter eggs pertaining to potential new plot points. But one new casting decision has been drawing the most attention.

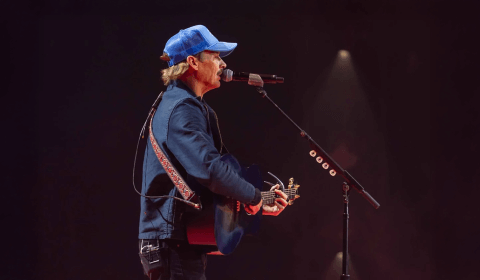

Park Sung-hoon, a cisgender actor, confirmed his role as a transgender woman in the latest installment of the series. The announcement sparked immediate backlash.

Critics argue that casting a cis man to play a trans woman perpetuates the exclusion of trans actors from the roles they are best suited to perform, and by extension, from the mainstream cultural landscape.

The debate isn’t new, and far from resolved. The representation of trans people on screen is littered with tokenism, fetishisation, invisibility, and appropriation.

The stakes are high because representation, particularly in media as globally significant as Squid Game, directly influences cultural perceptions of marginalised communities. The decision to cast a cisgender actor in a trans role feels like a step backwards, particularly in the context of Netflix’s most successful show.

But like most socio-political debates, the solution doesn’t sit comfortably in either black or white.

Hollywood has a long history of sidelining trans performers while routinely handing their stories over to cis actors. Eddie Redmayne in ‘The Danish Girl’, Jared Leto in ‘Dallas Buyers Club’ and Jeffrey Tambor in ‘Transparent’ are all acclaimed performances of trans characters given by cis male actors.

Park Sunghoon takes on the role of a Transgender in “Squid Game” Season 2, who enters the deadly competition in hopes of funding her gender-affirming surgery. pic.twitter.com/1yvcKEIOSC

— Daily Loud (@DailyLoud) December 5, 2024

The problem isn’t just about opportunity, though. When cisgender actors play trans characters, the authenticity of the portrayal often falters – not because of a lack of talent, but because trans experiences are lived experiences. Those intricacies cannot be approximated in method acting or rehearsals.

Casting cis actors in trans roles implies, however subtly, that trans actors are not capable of telling their own stories. It reinforces an already dominant narrative: trans people are a subject, not a voice.

That said, Park’s defenders argue that the criticism of his casting ignores the precarious position of trans actors in places like South Korea.

The country is hardly a bastion of LGBTQ+ acceptance. Stigma remains entrenched, and the backlash faced by those who dare to be openly trans is severe. Casting a South Korean trans actress in such a high-profile, global role would almost certainly invite scrutiny and harassment that could overwhelm the benefits of representation.

Director Hwang Dong-hyuk has hinted at these considerations, framing Park’s casting as a careful and deliberate choice. It’s worth noting that Squid Game is known for its trenchant social commentary; the show’s treatment of a trans character is unlikely to be frivolous.

Could a cisgender actor bring visibility to a trans story while shielding an actual trans actress from societal backlash? The real question might be whether that’s a compromise worth making.

If it’s simply about visibility, then Park’s casting might suffice. If it’s about equity and opportunity, it doesn’t.

This debate also raises an uncomfortable question for critics: how do we balance the global push for progress with the specific realities of cultural contexts? It’s true that we often come to popular culture debates with a distinctly Western cultural commentary, which erases the experiences of those in other global contexts.

It’s tempting to impose a kind of universal standard when it comes to representation. Trans roles should go to trans actors, full stop. But this standard becomes murkier when applied outside the Western bubble.

In a country where transphobia remains deeply entrenched, insisting on an ideal form of representation risks overlooking the lived reality of the people that ideal is meant to uplift.

For all the director’s assurances, it remains an uncomfortable fact that a cisgender man was chosen to tell a trans story. Whatever the reasons, that fact carries weight.

Still, there’s value in resisting the urge to oversimplify. The debate over Park’s role reflects a larger tension in the fight for representation: between principles and pragmatism, between ideals and the imperfect contexts in which they often have to exist.