Mourning is personal, not performative.

Every now and then, the death of a public figure takes you by utter surprise. It’s a very different feeling to the heavy pit of sadness that comes from looking at your phone and seeing yet more war, genocide, and human suffering.

These kinds of celebrity losses stop you in your tracks. They feel personal, intimate, and incredibly painful, but in a strange way that only parasocial relationships can breed. The worst part about this removed mourning is that you’re rarely given the grace to express it wholeheartedly.

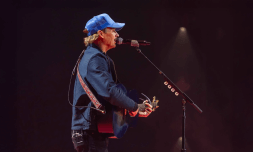

One such death has been the recent and tragic passing of Liam Payne. The singer, who achieved unfathomable fame as a member of One Direction, was just 31 years old when he fell from a hotel balcony in Buenos Aires on Wednesday.

Like many famous people, particularly those who achieve levels of stardom like his, Liam was somewhat immortalised in the public psyche. And thanks to social media, our proximity to celebrities fosters the understanding that we really know them – that they know us.

In the wake of his death, Liam’s fans have come out in a very public display of shared grief. From people gathering at his Argentinian hotel shortly after the news broke, to social media posts lamenting lost childhoods, the impact of Liam’s life and career is tangible.

But with such vast displays of mourning come the usual questions and raised brows. ‘How can you cry for someone you never knew?’ Those who have chosen to share their heartbreak on the internet are facing heavy-handed criticism, which is largely directed at the young, female demographic of Liam’s fanbase.

It’s the same vitriol that underpins our treatment of those in the limelight. Liam himself had been the subject of trolls and bullying for years before he died, and clips from recent months have been used to suggest the singer was suffering with mental health issues.

Moments after his death was first reported, TMZ shared images of the body on their website. It’s this endless obsession with surveillance and access that drives so many celebrities to the edge.

It’s also what desensitises us to the tragic loss of a young person – a brother, son, friend, and father to a 7-year-old – to such an extent that the first question asked is whether he was under the influence, sympathy quickly cut short if he was.

Both Liam and his relationship with fans have been cultivated by the strange, complex, world of fame. But the thirst for information and proximity that has seen thousands emerge from the woodwork to lament his wonderful personality and dazzling gift is not the same phenomenon that led hundreds of girls to rest flowers on a Buenos Aires street in the early hours of Thursday morning.

Fandom, in its messiness and massiveness, reminds us of the capacity individuals have to shape our lives. How art and those who make it are the driving forces of both culture, and the relationships we forge within it.

As Lucy Blakiston wrote, ‘I feel zero shame [about grieving], because as I’m writing this I’m listening to One Direction’s first album and my teenage years are flashing before my eyes in a montage. I feel like I’ve lost someone I knew – parasocial relationships will do that to you. Just because you never spoke to them doesn’t mean they didn’t in some way speak to you – a loss is a loss, and no one can tell you differently.’