Building a model of the future

To draw up the predictions, scientists combined 15 years of satellite tracking data from 350 whale sharks. They also noted details of the surrounding ocean’s conditions.

This information was then put into a computer model which predicted where whale sharks might live in three future climate scenarios: low, medium and high emissions.

In the worst case scenario, around 60 percent of countries will lose more than half of their whale shark habitat by the end of the century.

The eastern Pacific Ocean will see the biggest changes, with estimates suggesting that 5 million square kilometres of whale shark habitat – an area larger than the European continent – will become uninhabitable for the species.

The Atlantic Ocean, with its cooler waters, is expected to become more habitable for the sharks. While this might sound like good news, it is actually problematic, as this region is one of the busiest for seaports and shipping routes.

In a low-emissions scenario, where ocean temperatures level off and stop rising, the model predicted that the risk of ships hitting whale sharks would still increase by 20 times.

The lead author of the research Dr Freya Womersley stated: ‘Our study suggests that even the world’s largest fish is in danger from climate change. We found that preferred ocean habitats for whale sharks shifted in future, sometimes into completely new locations, often with cooler waters.

‘If the sharks move into these newly habitable spaces, it may provide them some respite from climate change, but it could also inadvertently expose them to risks such as unintentional fisheries capture, prey mismatches and collisions with ships.’

Why are whale sharks so vulnerable?

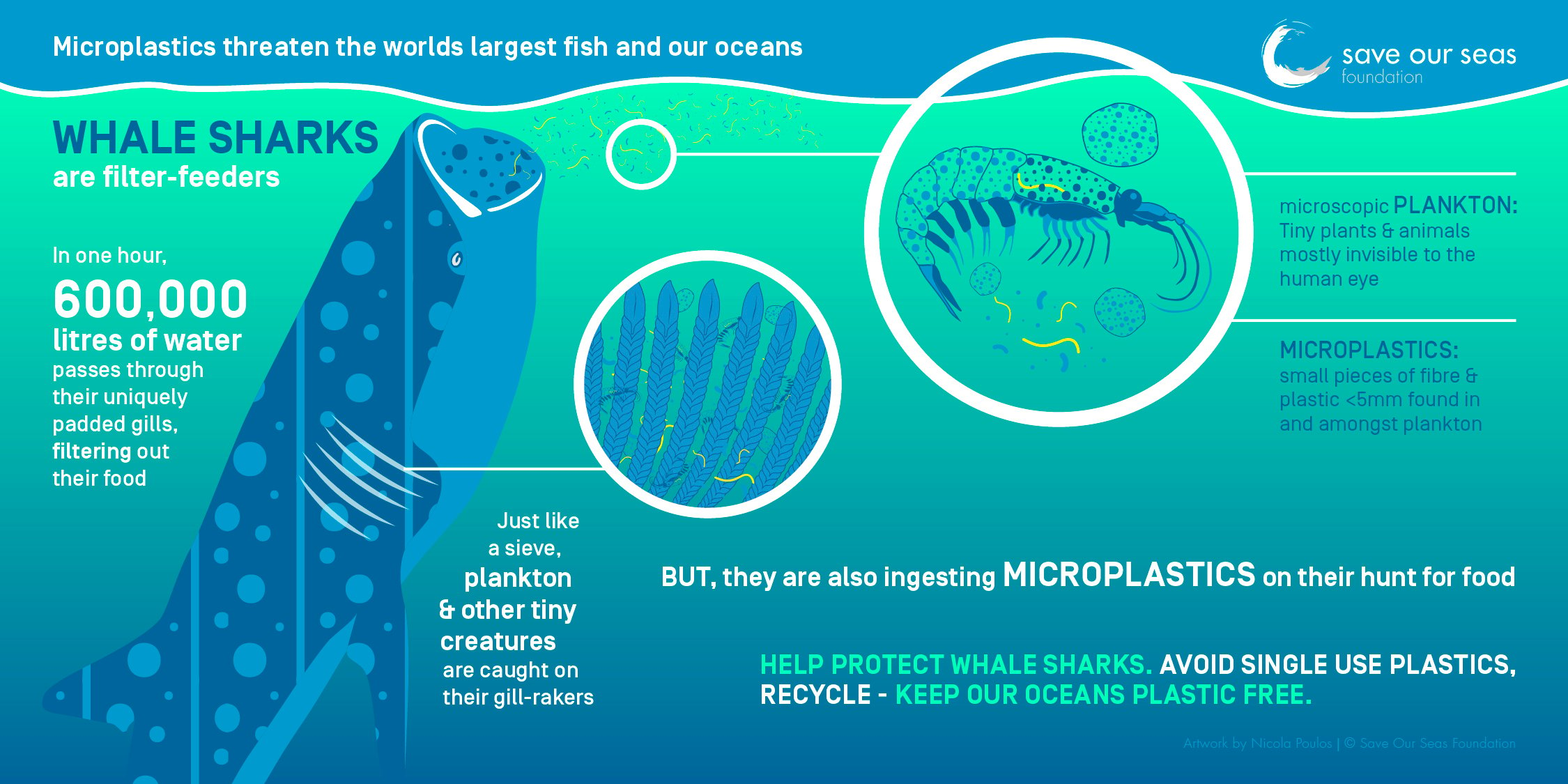

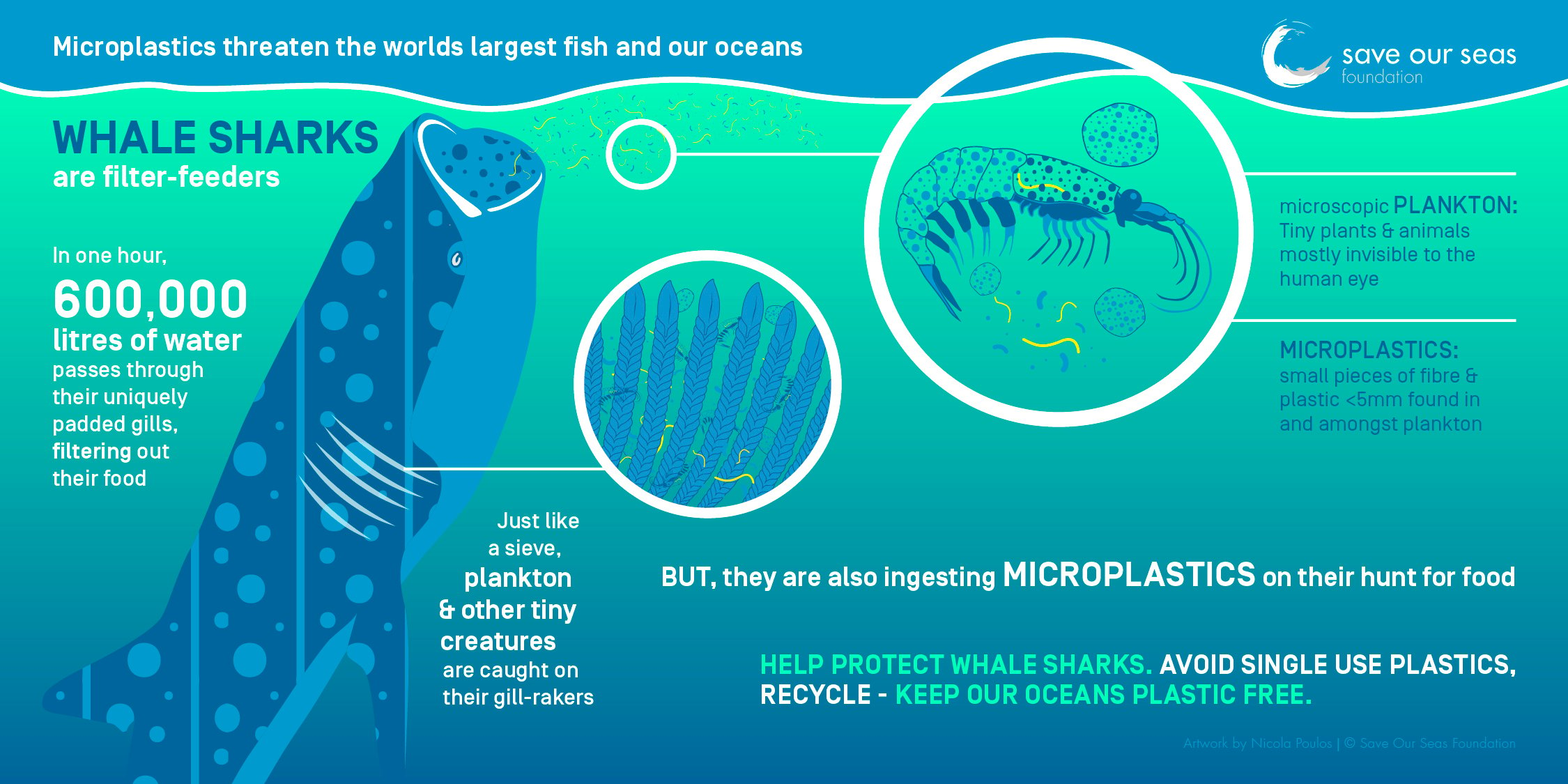

Whale sharks spend most of their time at the ocean’s surface, filter-feeding in waters located in the world’s most tropical regions.

This species gathers periodically near coastlines and is rarely found in waters that dip below 21 degrees Celsius due to their high sensitivity to temperature changes.

Despite their refined preferences, they are highly mobile animals. Sadly, their large size combined with their preference to stay at the surface makes them prone to being struck by large shipping vessels.

Over the last 75 years, the IUCN Red List has recorded whale shark populations steadily declining. Numbers have dropped by 63 percent in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, while the Atlantic Ocean has seen a 30 percent drop in whale sharks.

Rather than being hit by cargo ships, this decline has been attributed to a number of factors, including fishing bycatch, tourism, and ocean pollution.

Given that these majestic animals are already endangered, the scientists suggest that a two pronged approach should be applied to ensure they are kept as safe as possible.

First, we should ensure that the model’s worst case scenario does not become a reality. This means reducing greenhouse gas emissions, which would slow the warming of our oceans.

New policies could also be put in place to force ships to travel more slowly in high-risk areas, while distinguishing areas where ships should avoid could reduce possibilities of collusions.

If it is possible for humans to play their part in this species survival, why not do it?