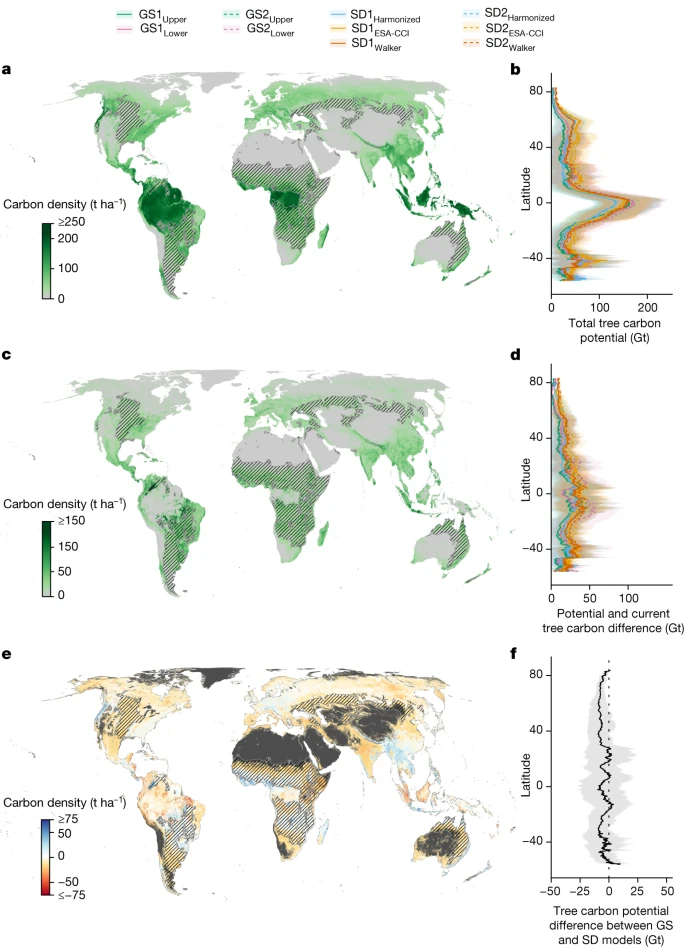

According to a new Nature study, protecting forests globally could potentially capture an additional 226 gigatons of planet-warming carbon, equivalent to about a third of the amount that humans have released since the beginning of the Industrial Era.

If you weren’t already aware, forests play a critical role in the survival of humanity, acting as natural shields that safeguard us from our own inherently destructive impact on the environment.

Hugely effective agents in easing global heating, these green spaces are one of our greatest allies against the climate crisis, soaking up the massive amounts of heat-trapping emissions we can’t seem to stop pumping into the atmosphere.

Unfortunately, amid unceasing deforestation for large-scale food production, the expansion of cities, illegal logging, resource extraction, and more frequent wildfires caused by rising temperatures (among numerous other drivers), over 420 million hectares of forest have been lost since 1990.

Every year, in fact, we destroy 10 million hectares of forest, amounting to an annual loss of forest areas equal to the size of Portugal.

Hoping to remind us of the increasing urgency we face to conserve and restore the Earth’s carbon sinks so as to avoid the life-threatening repercussions that the ecological emergency is set to bring about, more than 200 scientists and researchers have compiled their findings for a new study published in the journal Nature.

As it stipulates, protecting forests could potentially capture an additional 226 gigatons of planet-warming carbon, which is equivalent to about a third of the amount that humans have released since the beginning of the Industrial Era.

By allowing existing trees to grow old in healthy ecosystems and restoring degraded areas, the extra-storage capacity would be substantial, yet this cannot be achieved unless we stop relying so heavily on fossil fuels.

‘If we continue emitting carbon, as we’ve done to date, then droughts and fires and other extreme events will continue to threaten the scale of the global forest system, further limiting its potential to contribute,’ says Thomas Crowther, the study’s senior author and a professor of ecology at ETH Zurich.