After stripping away constitutional protections for abortion and expanding gun rights, justices have issued yet another momentous ruling – one that jeopardises the federal government’s ability to regulate emissions.

On Thursday, the US Supreme Court sharply limited the E.P.A’s ability to regulate carbon pollution from fossil fuel-fired power plants, making it much harder for President Biden to achieve his goal of cutting greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030.

The 6-3 ruling follows a recent decision to scrap constitutional protections for abortion and vastly expand gun rights in America, which has sparked immense controversy worldwide.

It is the most important climate change case to come before the Supreme Court in more than a decade, at a time when climate policy is floundering as a result of the global supply chain crisis and the Russo-Ukrainian war.

Dealing what many are calling a devastating blow in an era of environmental crises (global heating increasingly stands out as the single greatest emergency humanity faces, driving extreme temperatures, droughts, flooding, famine, wildfires, and ecosystem collapse) it eliminates one of the only remaining avenues for systemic federal climate action.

It also signals, according to the New York Times, that the Supreme Court’s newly increased conservative majority is ‘deeply sceptical’ of the power administrative agencies hold to address pressing issues both the nation and the planet are currently confronted with.

How West Virginia v E.P.A became a reality

‘Capping carbon dioxide emissions at a level that will force a nationwide transition away from the use of coal to generate electricity may be a sensible solution to the crisis of the day,’ Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in his opinion.

‘But it is not plausible that Congress gave the E.P.A the authority to adopt on its own such a regulatory scheme.’

Simply put, he argues that an independent agency ought not have the authority to dictate how entire states manage their emissions, especially if this means they are forced to do so at a ‘severe economic cost.’

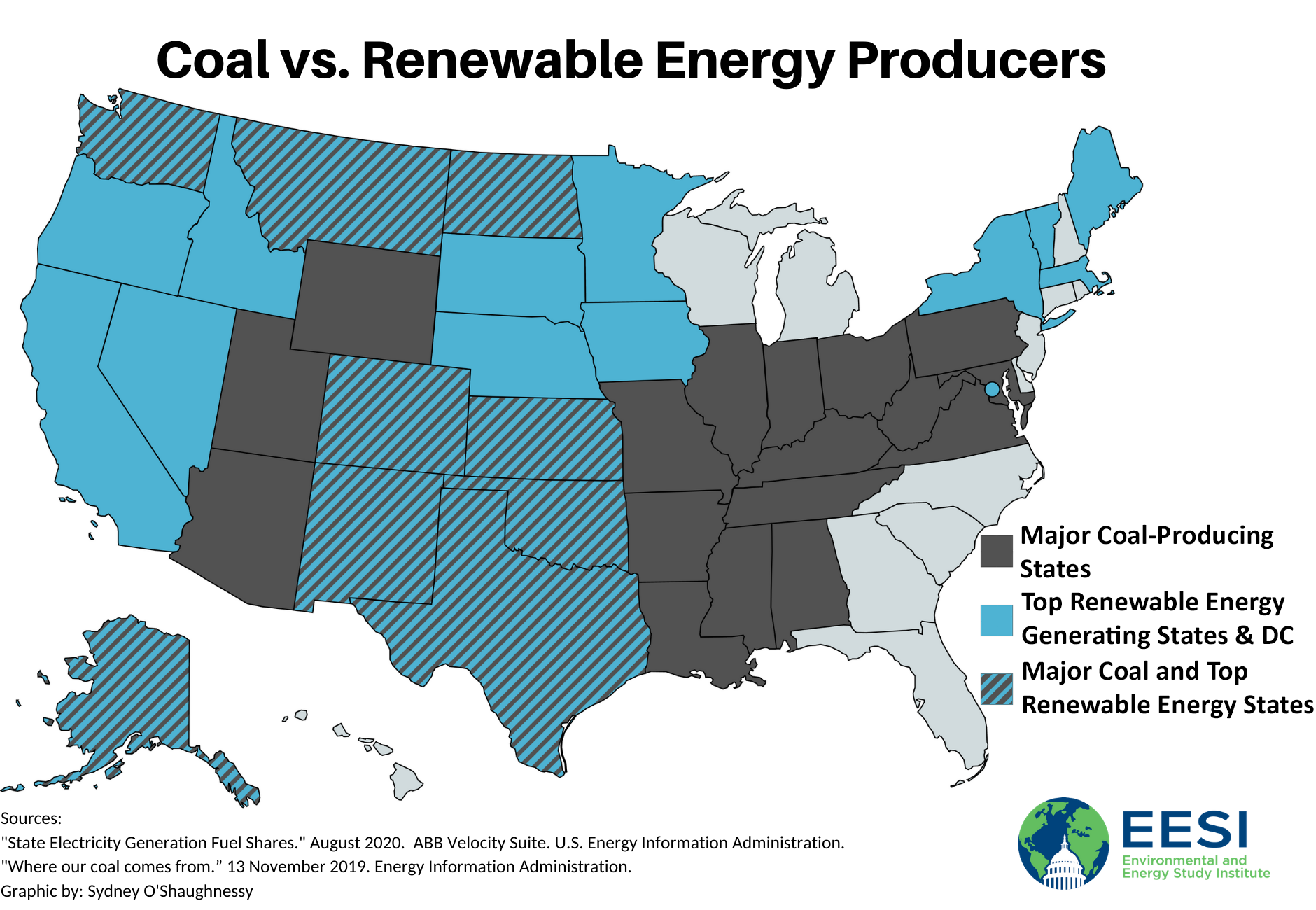

This specifically applies to a host of mostly Republican-led states and some of the US’ largest coal companies that the West Virginia v E.P.A case was on behalf of.

In light of their concerns over Obama’s Clean Power Plan and the alleged ‘job-killing regulations’ it has induced since being established in 2015, the majority ruled against permitting the E.P.A to impose sweeping measures without prior approval.

This means that while the Supreme Court hasn’t completely prevented the E.P.A from putting forward regulations in the future – such as the reshaping of the power grid by obliging states to rely more heavily on cleaner sources like solar and wind power – it does say that Congress would have to expressly sanction them.

Not only this, but under the court’s ruling, when the E.P.A develops national emissions guidelines for existing power plants it must rely only on technological solutions that can be applied by existing plants, without assuming a fundamental change in their nature.

In other words, guidelines must be drafted that allow coal-fired power plants to remain exactly as they are.

‘A decision of such magnitude and consequence rests with Congress itself, or an agency acting pursuant to a clear delegation from that representative body,’ continues Roberts.

‘Separation of powers principles and a practical understanding of legislative intent require clear congressional authorisation before systemic regulations affecting the entire power network can be drawn up.’

The conflict between economic growth and environmental protection

As Roberts declares (an outlook shared with all five of his conservative colleagues), the Clean Power Plan has affected a ‘significant portion of the American economy.’

What this alludes to is a defining factor of the debate over environmental regulation: that a shift away from revenue-generating industries – regardless of the sobering reality that they play a key role in the climate crisis – will instantaneously denote major financial repercussions.

It’s for this reason that the Supreme Court has set out to return autonomy to individual states, with an ultimate goal of letting the officials governing them regulate as they see fit.

A direct response to West Virginia’s argument that ‘unelected bureaucrats’ at the E.P.A should not be allowed to reshape its economy by limiting pollution, it also threatens the Biden administration’s ability to impose new limits on tailpipe emissions from cars and trucks and on methane emissions from oil and gas facilities.

Additionally, the Supreme Court maintains that there can be ‘little question’ that the rule ‘does injure the states’ since they are the object of its requirement that they more stringently regulate emissions within their borders.

On this note, they assert that the ruling will bring about even stricter regulations, yet with the responsibility lying solely in the hands of the states – a substantial number of which will no doubt continue to uphold ties with coal mining due to its economic benefits – this has raised alarm bells among climate activists and policymakers working to curb emissions.

Providing states with the duty to handle their own environmental impact permits them and them alone to take charge of their economies, which is believed will appease taxpayers.

However, divvying up accountability even further amid the Earth’s destruction is widely considered a recipe for environmental disaster.

Consider too that US fossil fuel-fired power plants are one of the largest sources of emissions in the world (they produced 1.55bn tonnes of CO2 in 2020). The 19 states which brought the case have historically made little progress on reducing their emissions.

In fact, they made up 44% of the US’ emissions in 2018, and since 2000 have only achieved a 7% reduction in their emissions on average.