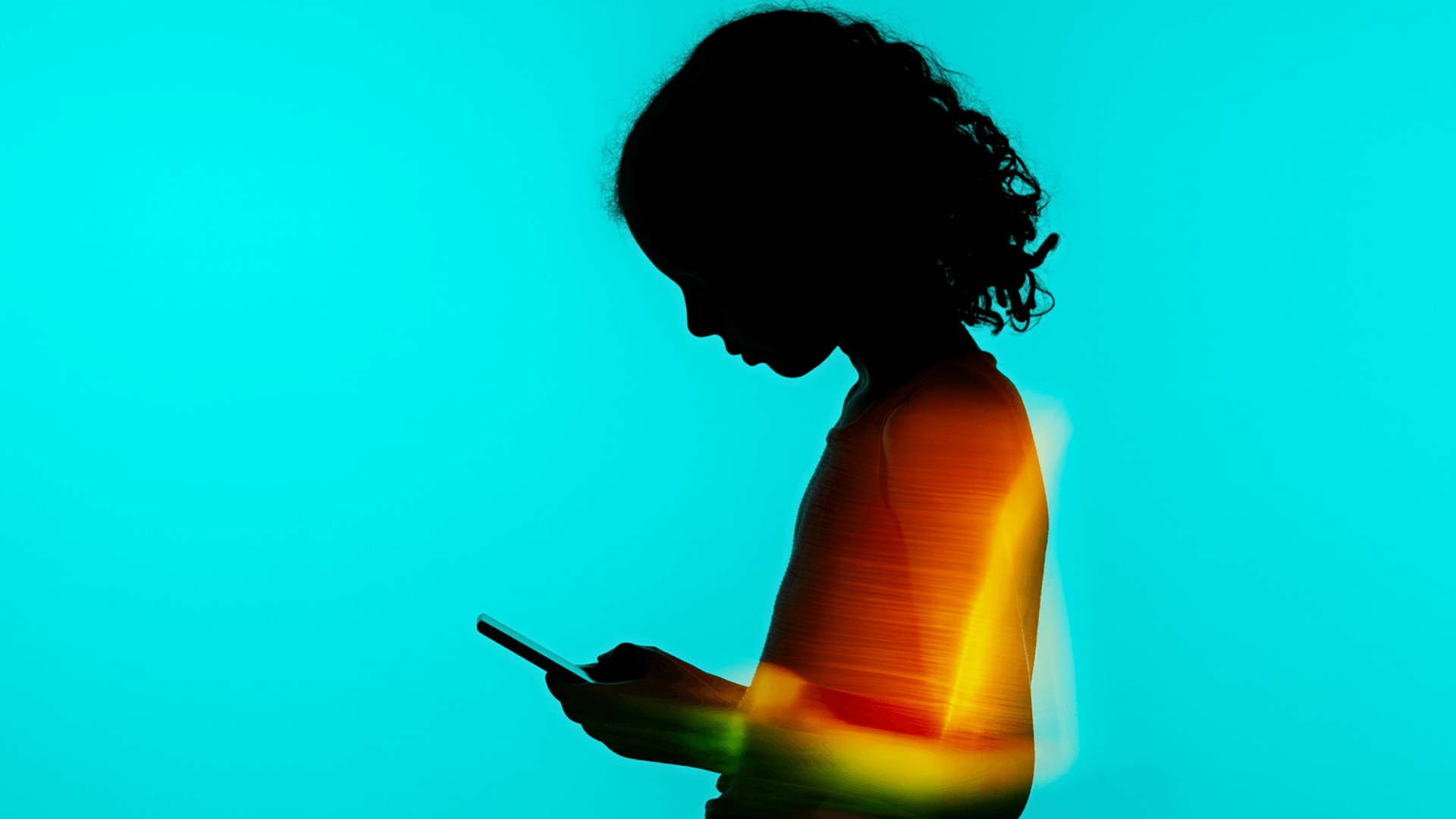

The growing dependency on tech is driving us apart. But there are ways to prevent being swallowed by your phone.

‘84% of Americans say they are online either several times a day or ‘almost constantly,’ writes Christina Caron. I must amidst I didn’t even bat an eyelid at that statistic – which says it all, really.

I’ve used 2025 as a sort of ‘health kick’ year. Newly single and determined to shelve a period of low mood and insecurity, I set out at the start of this year with a very specific set of goals. I’ve achieved most of them, which feels amazing to say given it’s only August.

But despite running a marathon, reading more books, ditching processed food and cutting back alcohol, there’s one thing I’ve struggled to tackle – and that’s an overwhelming dependency on my phone.

When I really think about it, the amount of time spent staring at a screen is overwhelming. I use a laptop all day at work, then come home and watch TV, maybe do a bit of extra work on another laptop, and scroll intermittently on my phone throughout. The only times I’m not sucked into the digital vortex are when I’m walking from A to B, running, or spending time in the gym.

One habit I’ve picked up is leaving my phone on the side rather than bringing it to bed with me. The half an hour before I fall asleep is now taken up with reading a book rather than doom scrolling. As someone who’s suffered from terrible insomnia, I can safely say the positive effect on my day is tangible.

But I still live with constant ‘phone noise’ (as I like to call it). I’m ashamed to admit that there are times when I can’t help but check my phone mid-conversation. It’s not that I’m even interested in what I might find on there (spoiler; absolutely nothing. I’m one of those people who rarely receives a message), but it’s become a physical reflex.

My thumb aches to scroll for mindless content. My arm is constantly reaching to check my phone is there, panic setting in if it isn’t.

So no, I wasn’t particularly surprised to read that almost 90% of the American populace are also addicted to their mobile device.

Don’t scroll your life away.

Phone addiction is the silent epidemic we’re all ignoring.

It fuels your anxiety, wrecks your sleep, and robs you of precious moments every single day.

Here’s how to break free (and take back control for good): pic.twitter.com/10O9fVZlQ2

— Chelsea (@holistic_chels) August 9, 2025

And not for want of trying, young people are increasingly seeking ways to detach from the digital – particularly as our jobs move online and we grow ever more isolated from the physical.

The good news is, there are ways to combat phone dependency. And plenty of people have written about them.

Catherine Price’s book ‘How to Break Up With Your Phone’ asks us to consider the ways a digital dependency shapes our lives on a grander scale.