Those diagnosed with type 1 diabetes are more than twice as likely to experience an eating disorder than people without, yet specialists continue to encourage carbohydrate-counting and food logging. How can diabetics avoid sliding down the slippery slope of disordered eating?

Finding a balance between the right intake of food versus insulin is a dilemma diabetics face from the very outset of their diagnosis. So it’s only natural that, at the start, they will tend to lean on their practitioners for guidance.

Unfortunately, while diabetics might get the right physical health support, they often find themselves feeling at a loss with their mental health. Glucose levels fluctuating lead to an overwhelming sense of feeling out of control, which feeds the need to micromanage that which is still in their control, including food and exercise regimes.

‘But everyone with diabetes – whatever the type – should be able to find a place of food freedom and enjoy an easy relationship with food,’ says Beth Edwards, a Bant-registered nutritional therapist with an MSc in health psychology.

‘It takes awareness, grace and a lot of patience,’ she adds.

Edwards, who helps people with type 1 diabetics to find balance and live better through nutrition, gentle coaching and lifestyle support, says disordered eating as a diabetic can encompass myriad behaviours, including the restriction of insulin to lose weight, also known as diabulimia.

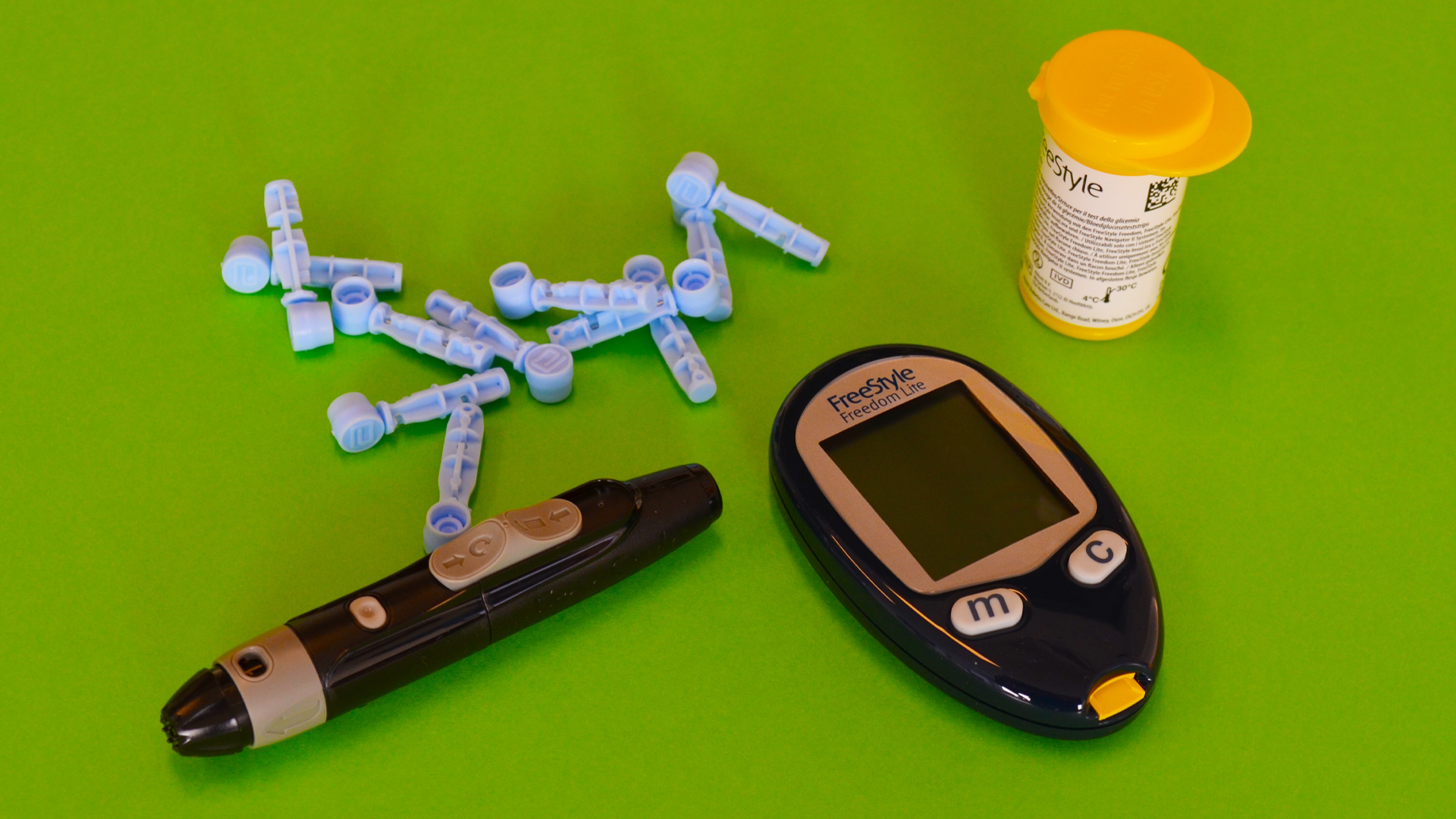

Type 1 diabetes is when the body attacks the pancreas, which in turn stops functioning properly and the body loses its access to a reliable source of insulin. Insulin is needed to help the glucose that enters our bloodstream from our food and drink intake to be turned into energy.

Without it, glucose builds up, but we can’t produce the energy we need to do everyday things.

Food management

Food plays an intense role in type 1 diabetics’ lives, because everything we eat has the potential to impact our blood glucose levels (BGLs) and this can lead to complicated feelings around food and restriction, Edwards says.

One way food directly impacts our insulin regime is if BGLs go out of range after a certain food. ‘So removing that food might feel safe,’ Edwards adds.

For years after she was diagnosed, the practitioner was afraid of eating bananas. She tells me that fruit is often something on the list of restricted foods, so she didn’t allow herself to eat bananas.

‘It’s easy to see how those of us with type 1 diabetes can view food as good versus bad, or allowed versus avoided, or why we would sacrifice steady BGLs for a bit of the forbidden fruit,’ Edwards says.

To best manage our levels, specialists teach diabetics how to carbohydrate count, an activity that requires daily measurements of carbohydrate intake, accompanied by an injection of insulin to cover that food.

Edwards explains that this may also require an individual to establish a ‘carb ratio’ – for example, one unit of insulin to 10g of carbohydrates. It is an effective management tool, but what gets left behind is the emotional and psychological impacts that result from measuring food in this way, she noted.

‘Food is so much more than how many carbohydrates it contains,’ she says. ‘It’s about connection with loved ones, it’s comfort, it’s taste, it’s a restaurant outing or a Friday night takeaway.’

Though counting carbohydrates is an ‘inevitable’ part of managing type 1 diabetes, we’re seeing more psychological support available – especially for children and families, she says. Although the availability of these services is often a ‘postcode lottery’.