A recent article by ‘Dazed’ suggests famous white women, most notably the Kardashians, have abandoned the Black aesthetic they’ve appropriated for the past few decades. But can racial and cultural identity be reduced to a ‘look’? And does the white monopoly over global beauty standards show any signs of waning?

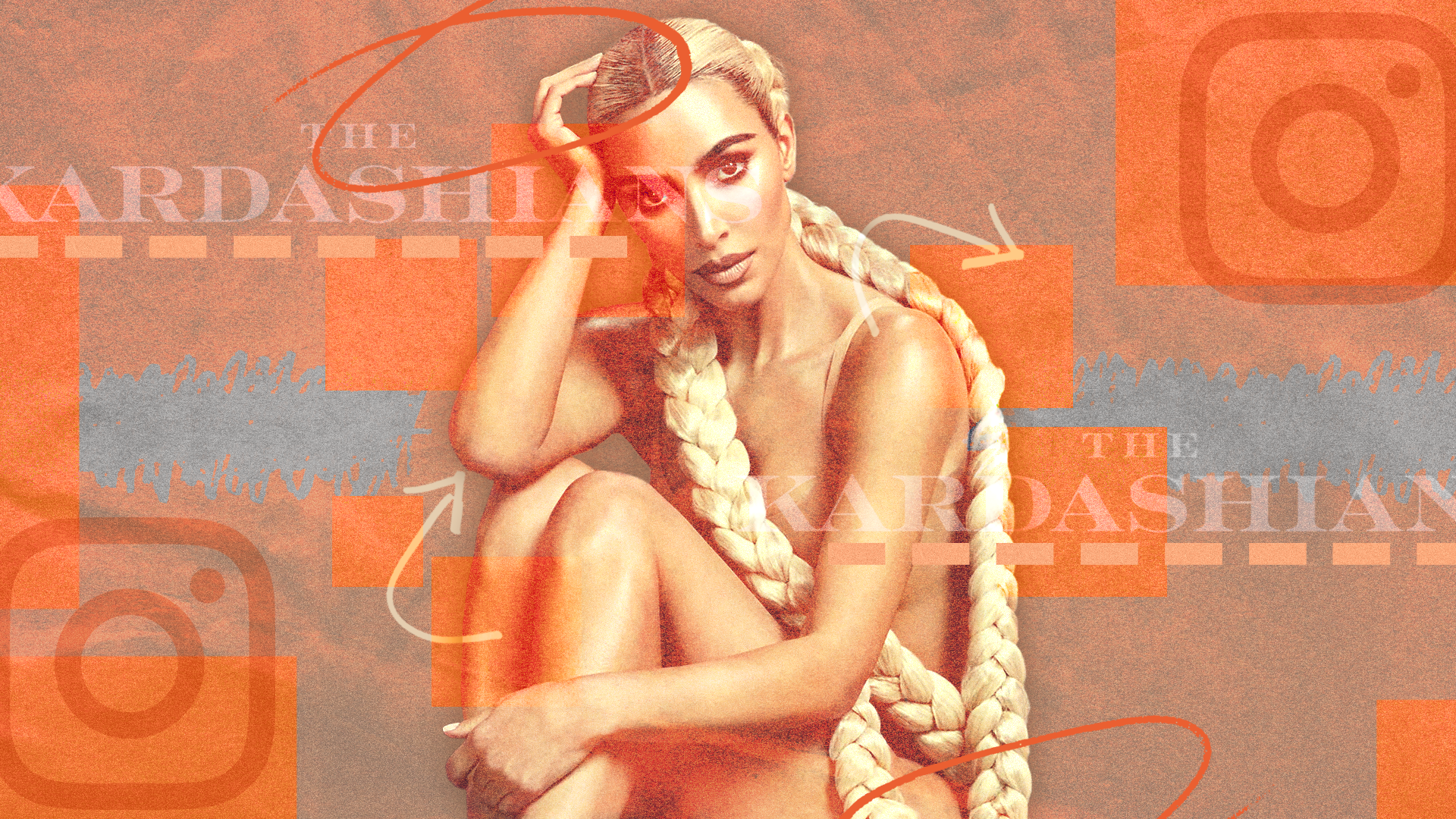

Side-by-side comparisons of Khloe Kardashian have been making the rounds online, pointing out the sudden disappearance of her infamously large bottom. Her sister, Kim, has also lost a drastic amount of weight, dropped the fake tan, and bleached her hair.

Fascination with the Kardashian aesthetic has propelled the family to global fame, and many would argue it’s the only thing sustaining it. But it’s not just flawless skin and enviable curves that have made Kim, Khloe, and Kourtney the blueprint for modern beauty.

For the past decade, discussions of cultural appropriation have surrounded the Kardashians. From cornrows to BBLs (Brazilian Butt Lifts), the sisters have adopted Black aesthetics and cultural signifiers to push a certain image of themselves.

This image has extended into nearly every aspect of their lives. They repeatedly date and marry Black men, have mixed race children, and publicly yearn for a stereotyped ideal of Black womanhood.

After her baby was born in 2018, Kylie Jenner commented, ‘the only thing I was insecure about, she has – she has the most perfect lips in the whole entire world. She didn’t get those from me.’

One of the most obvious appropriations of a Black aesthetic came when Kim famously posed for Paper Magazine in 2014. Her images were shot by Jean-Paul Goude in a recreation of shots from his 1982 series ‘Jungle Fever’, starring Grace Jones.

The original series was a caricature of the Black female body, featuring shots of Grace in a cage hissing like a cat. Other images exaggerated sexual body parts, posing an uncomfortable affinity to 19th-century illustrations of Saartje Baartman.

‘Blacks are the premise of my work’ Goude said of the original series. ‘I have jungle fever.’

But despite this long history of appropriation and tone deaf social commentary, it seems the Kardashians’ affinity for Blackness has reached its climax.

Over the past few months, there’s been a notable change in Kim. Besides her drastic weight loss, blonde hair, and smaller behind, the reality star’s physical changes have been coupled with a new self-constructed public image.

Some have suggested that Kim’s new law career has motivated this abrupt aesthetic reinvention.

Not only has passing the bar seen Kim noticeably move away from the socialite sex-symbol narrative that led her to fame. She has also placed emphasis on the legal system’s treatment of African American men and women, adopting the position of ‘white saviour’.