the thing that shaped Gen Z the most

Welcome to the latest edition of The Gen Zer. This week we’re taking a deep dive into how phone use has affected young people and what we should be doing about it now. Read on below . . .

Over the past few months there has been an explosion of articles on how phones are affecting young people, spurred in part by Jonathan Haidt’s recent book The Anxious Generation (which I’ve spoken about previously here).

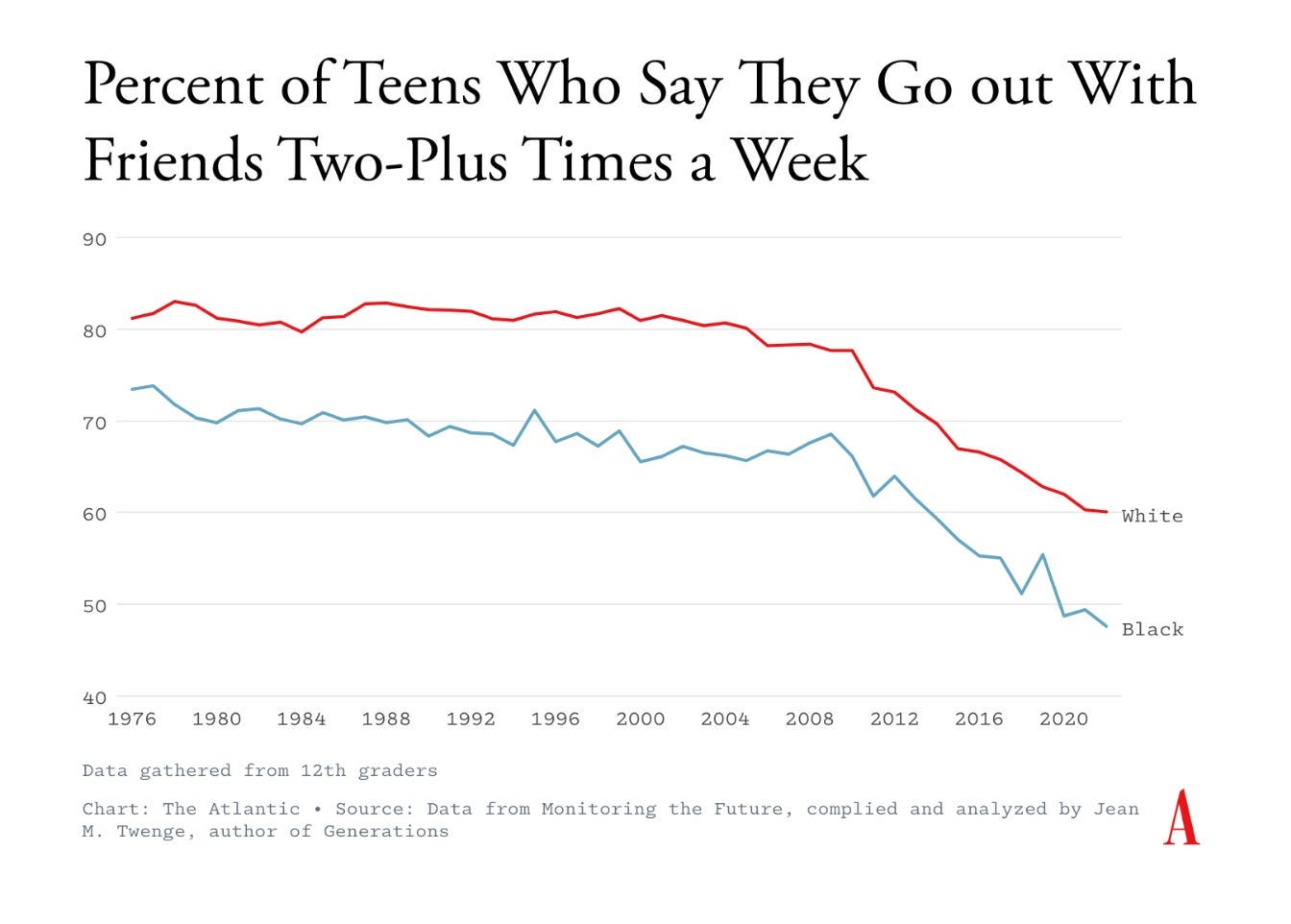

Last week I came across a great article by Magdalene J. Taylor. The essay is titled It’s Obviously the Phones, and addresses how phones have played such a large role in the decline of sex (and, more widely, intimacy and connection) in modern society. Taylor points out how the decline in sociability amongst young people increased dramatically from 2008 onwards, one year after the release of the first iPhone. Here’s a pretty telling graph from The Atlantic:

Taylor’s article made me think of another great article, this time by Erik Hoel, called What the heck happened in 2012? In short, Hoel talks about how so many graphs show 2012 as a tipping point, the year a general decline or increase suddenly became much more dramatic. For instance, depressive symptoms in school children began to rapidly rise around then, and outcomes in reading and mathematics began to drop.

The changes in 2012 seem to permeate every part of society: birth rates began dropping sharply, songs in the charts became much more explicit, remakes began taking over Hollywood, conversations around prejudice exploded in the media, self harm in teenagers rose dramatically, mental health in adults dropped.

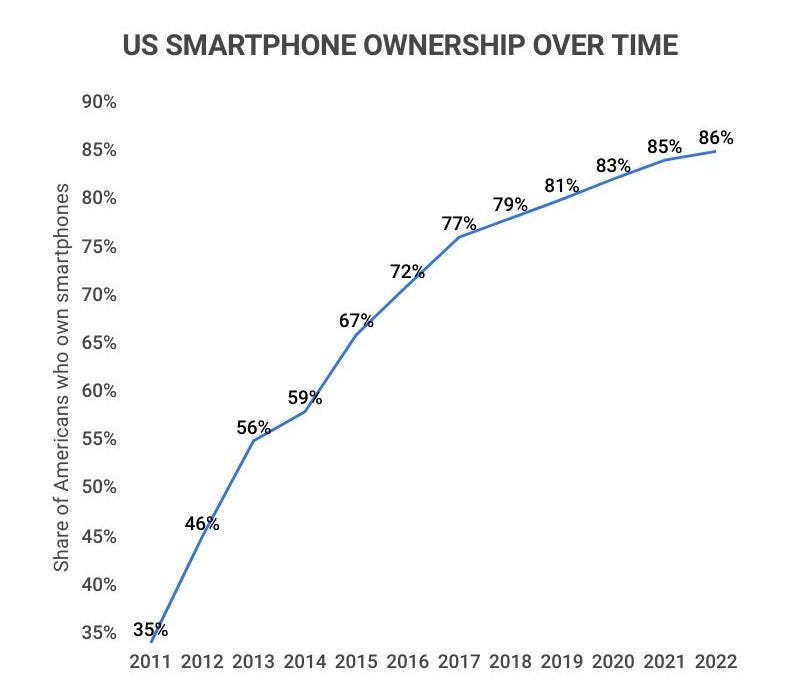

There are many causes we could point to, of course; the years around then contained a lot of economic, international and social turmoil. Tellingly, however, 2012 was also the exact year that the majority of the US switched to owning a smartphone, with a similar timing in other developed countries. Hoel is pretty direct with his conclusion: 2012 was the year the modern world was invented. (For the Mayans, of course, it was also the year the old world ended.)

This week, government ministers in the UK are considering plans to ban children under 16 from accessing social media. A government petition for this has already reached over 76,000 signatures — close to the 100,000 needed for the petition to be considered for debate in Parliament.

We might not have to wait that long, however, since there’s been increasing sign that Labour is already seriously considering it. Peter Kyle, the science and technology secretary, is said to be watching developments in Australia, which last week announced plans to ban under-16s from Facebook, Instagram, X, TikTok and the like. The health secretary, Wes Streeting, has also expressed support for the bill.

These things often seem to happen in 10-20 year cycles. Something new is introduced, gets rapidly adopted, and then gradually the drawbacks get more and more obvious until there is finally a societal — and political — pushback. We go too far one way, then pull back towards a workable mean.

Haidt’s book has been a large catalyst in the current conversations that are happening worldwide. We’ve all seen countless headlines about how anxious, depressed, lonely and whatever-else Gen Z have grown up to be. Until now these have all seemed like disparate things, caused by a whole host of different factors, which of course is partly true. But the conversation has recently taken smartphones and social media as its focal point.

Most of the other causes stem from these two things, from polarisation, to misinformation, to body-image issues, to overstimulation, to 24-hour news cycles, to reactionary movements, to a growing gender divide, to all manner of things that young people have been struggling with for years. We are an anxious generation — the wealth of data paints a pretty clear picture — and now, finally, steps are being taken at a societal level to try and deal with this. With luck, generation alpha may dodge some of the insanity we were left with during our formative years.

The shift from reading newspapers to getting your news from TikTok means that we don’t even agree on the basic facts; we have no common ground with each other, nothing to breach the political divide. Being always connected can be exhausting. Blue light interferes with your sleep. Seeing your friends having fun on Instagram is only going to increase the FOMO that a teenager feels if they’re not invited.

Catherine Shannon, in her essay Your phone is why you don’t feel sexy, offers a really great analysis of some of these problems. She dives into how getting used to instantaneous access to everything ends up making us act like ‘demented Roman emperors, at once bored and deranged, summoning whatever we want at any time.’ She puts it this way:

![]()

Phones used to be sexy. A call from an unknown number. A little black book. Your heart pounding as you checked your answering machine. Calling someone from a payphone. Hearing someone say, “It’s for you.” This was romance.

Now, we use our phones—which are more like handheld supercomputers than phones, let’s be honest—to rot in bed on TikTok, slide into someone’s DMs, and thumbs-up react to a text. And this is to say nothing of the ubiquity of pornography or the hair-raising prospect of being added to the WhatsApp bachelorette group chat (LADIES: THIS IS YOUR FINAL REMINDER TO RESPOND TO THE DOODLE). I think we can all agree: this is a nightmare.

I’d highly recommend Shannon’s article, if you haven’t read it already. It’s so refreshing to see these conversations spark into life online — and yes, this is happening mostly online. Despite everything I’ve said, I don’t think anyone’s expecting us to cut the cables on the internet. Personally I wouldn’t even say that the internet is what’s wrong. From having access to almost all the research that humanity has undertaken, to calling your friends or family, the internet is pretty neat. What’s wrong, I think, is our obsession with short form content and our propensity for seeking information from unreliable sources.

Everyone I know or have encountered who has deleted their social media accounts has felt a lot better — I don’t know anyone who’s regretted it. The idea of doomscrolling for hours feels so weird once you cut it out of your life entirely. But I’m sure these people still go online, maybe just from their laptops rather than their phones. They still watch videos, just longer ones. They still check the news, just via newspaper articles rather than from some dude on TikTok.

And they’re still immersed in the common culture: they still read books, go to the cinema, watch documentaries, read essays on Substack, etc etc. Changing our relationship with phones and social media doesn’t have to come at a great cost. At least, nothing more than a few withdrawal symptoms, until you realise that there’s so much more to life and humanity than what you see on that little handheld screen.

See also:

- Gen Z is healthy and boring

- Can book clubs help solve Gen Z loneliness?

- The nolo generation: why are Gen Z ‘sober curious’?

Gen Z around the Web

Should smartphones be banned in schools? (financial times)

Following on from what I’ve written about above, some schools are starting to completely ban smartphones, citing research that shows a link between social media apps and eating disorders, depression and anxiety among young people. According to a poll for the FT, almost half the British public support such a ban. Read more

How teens and parents approach screen time (pew research)

This research is from earlier on in 2024, though I thought it’s an interesting addition to what I’ve written about above. Some of the key takeaways include:

– 72% of U.S. teens say they often or sometimes feel peaceful when they don’t have their smartphone.

– 39% of the teens have cut back on time spent on social media.

– Almost 40% of teens and parents say they regularly argue with each other over time spent on their phones. Read more

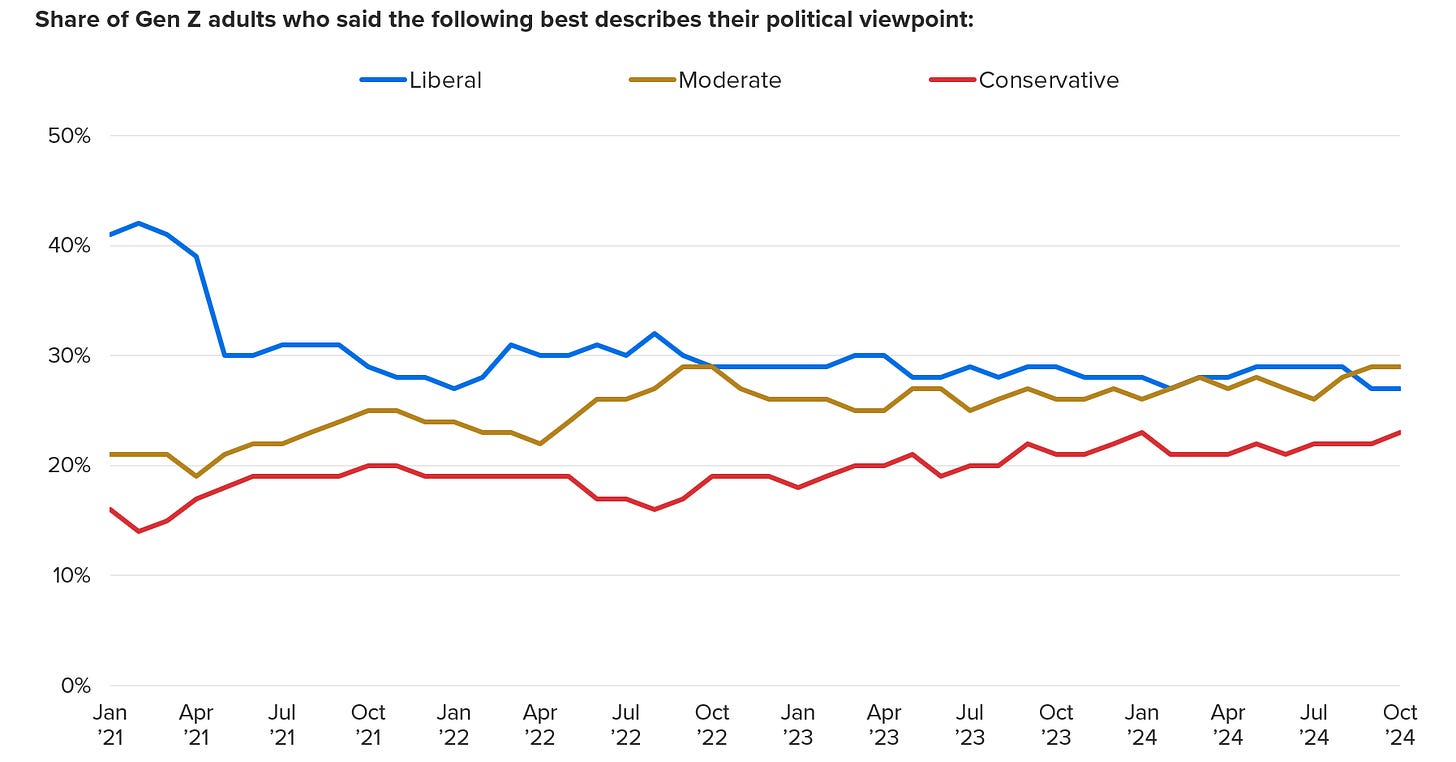

Gen Z adults are getting more moderate (morning consult)

A deep dive into hundreds of thousands of survey responses reveals that, on politics, Gen Z adults have been getting more moderate and less liberal in recent years, driven largely by economic concerns. As a wider trend, there seems to be much more of a desire for certainty and control, and even an increase in how Gen Z value things like routine, traditions, privacy and faith. Read more

The lost boys of Gen Z (the conversation)

There’s a narrative that young people are becoming ever more progressive, but in the past year or two a growing number of young men have been diverging from this trend. These ‘lost boys’, as they sometimes get called, can be characterised by feeling overlooked and short-changed by left-wing politics and current economic outcomes, and are increasingly struggling with unemployment, addiction and poor mental health. For figures like Jordan Bardella or Donald Trump, these young men have proven an increasingly reliable voter base, with Trump’s popularity among young men surging by 15 percentage points compared to 2020. Read more

Why young people are turning their backs on busyness (thred.)

The ‘soft living’ movement was born in part as an alternative to the #girlboss trend. In other words, amongst things like the cost of living crisis, threats posed by climate change and worsening armed conflicts, many Zers are valuing ambition less in favour of a more balanced life. Read more

That’s all for this week! Make sure to subscribe for the latest on Gen Z and youth culture, and check out The Common Thred for a weekly roundup of the latest news, trends and thought pieces.