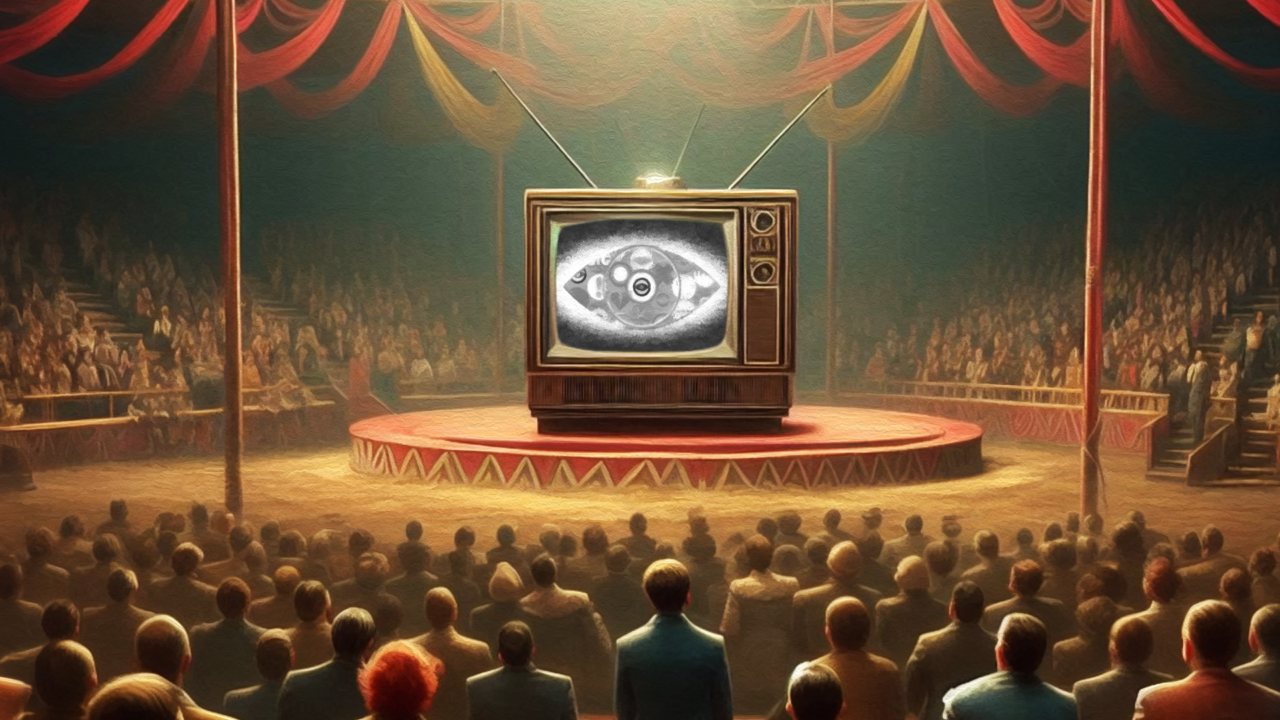

The one who doesn’t know their history is condemned to repeat it. Echoes of the infamous freakshows can be seen in society’s clamour for reality TV fame.

You walk into a completely dark room. In front of you, there is a necklace that when you put it on shows the count of your followers on social media. From that moment on this accessory defines your value. It seems to be the intro of an episode of Black Mirror that depicts our terrifying future, but no, it’s just the beginning of Netflix’s new viral reality show ‘Influencer’.

The show is initially easy to watch as it features familiar Korean entertainment personalities competing to be named ‘The most influential’. However, the novelty rapidly wears off.

The use of reality shows as a way to conduct social experiments – with the excuse of bringing people closer by dangling the carrot of money or fame – is not uncommon and is widely accepted by society.

This is thanks to the endless buffet of franchises shown by different television broadcasters. We’re conditioned to see them as acceptable form of content to entertain the public, but have you ever stopped to ask yourself what separates this from the infamous freak shows.

During this grim era, folk with genetic abnormalities were exploited under the premise that they would be given a once-in-a-lifetime job opportunity, a sense of belonging, and even life in exchange for entertaining the public for a few minutes. With fictional backstories established to grab the audience’s attention, the majority shunned honesty and embraced their façades.

If we compare it to reality shows like ‘Influencer,’ truthfully there is not much difference. Humiliation and risking one’s physical well-being seem to be an acceptable currency to exchange for recognition and social media interactions.

Participants would shave their eyebrows, spread dating rumours, consume extra spicy food, and even expose their own private lives just to ‘survive’ the round.

While we can argue that the contestants are there voluntarily and that these actions were dictated by themselves, equally we can acknowledge the dehumanizing nature these shows promote. In one round, a human auction saw participants bet the value of their necklaces to team up with another influencer. ‘X player bought Z player,’ the host announced.

But why should we question these seemingly inconsequential moral dilemmas in our daily lives? I mean, reality TV has been around for decades now.