Blake Lively proves our desire to watch successful women burn is both pervasive and insidious. But are times finally changing?

When Colleen Hoover’s wildly successful novel ‘It Ends With Us’ was released as a feature film last year, the media went wild. But besides the dedicated fans who lined up to see their favourite characters on the silver screen, much of the attention shifted to on-set issues.

It was somewhat surreal that, while telling a story about domestic violence, the cast was reportedly dissolving into their own highly publicised conflicts. These mainly involved the two leads Blake Lively and Justin Baldoni.

And while little was divulged by either party at the time, it was clear from Baldoni’s absence on the press tour and a rapidly growing barrage of hate towards Lively – Hollywood’s former ‘girl next door’ – that there was truth to the rumours.

In a matter of weeks, Lively went from beloved star to manipulative villain, thanks in part to a resurfaced interview in which the actress rebuffed a well-intentioned journalist.

And Lively’s comments when promoting ‘It Ends With Us’, including the suggestion that fans ‘put on their florals’ to watch a film which tackles deeply uncomfortable subject matter, seemed to be the tipping point in what became a widespread hate campaign.

Comments comparing Lively to Amber Heard, calling for her downfall, and showering Baldoni with support swept social media for the latter part of last year.

But just when the ‘I hate Blake’ train seemed to have left the station, the New York Times released an investigative piece outlining Lively’s decision to sue Baldoni for misconduct and sexual harassment.

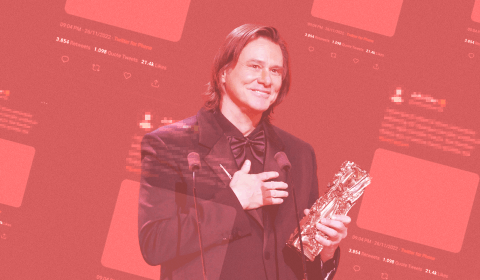

The woman behind this account was one of the biggest grifters from the Depp/Heard trial, publishing over 240 videos with lies and misinformation about Amber Heard. She even bragged about contacting Depp’s lawyers.

Her latest target is now Blake Lively. https://t.co/5AcnirulbG pic.twitter.com/lZNIThrcKC

— la bella vita (@drugproblem) January 3, 2025

Lively has alleged that both Baldoni and lead producer, Jamey Heath, violated physical boundaries on set and made sexually inappropriate comments toward her during filming. These included improvised and unwanted kissing scenes with Baldoni, not providing a closed set during intimate scenes, and an encounter in which Heath showed Lively videos of his naked wife.

When these reports first surfaced, many were quick to dismiss Lively’s claims as a vapid attempt to renew her damaged public image. But the length and detail of the New York Times report shed significant doubt on Baldoni’s innocence.

Most striking was the paper trail linking Baloni to a high-profile PR representative, whom he appeared to hire in the interest of ‘destroying’ Blake via an intricate smear campaign.

Everything from planting negative comments online to spreading social media content that painted Lively in a poor light.

By all intents and purposes, it worked.

As details came to light of Lively’s lawsuit, so did screenshots of previous comments hurled at the actress. It was a mirror to the ease with which we choose to hate women. Even the most successful and beloved.

‘We [are so] influenced by group-think on the internet’ said Polyester’s Ione Gamble. ‘Like, people just running away with one narrative. And you’re like ‘yeah!’ because your whole algorithm’s getting tailored towards Blake hate.’

Baldoni’s own crisis management representative, hired to spearhead the destruction of Lively’s public image, even said it herself – in a text to Baldoni’s team now immortalised in viral screenshot; ‘It’s actually sad because it just shows you have people really want to hate on women [sic].’

It’s actually crazy that we have a document where Justin Baldoni’s PR team said they were going to do a smear campaign using people’s hatred of women to paint Blake Lively as a mean girl diva, and it’s still working

— ✨️Paige✨️ (@bejeweledpaige) January 8, 2025

It highlights a pattern of behaviour in our culture, in which the support of women – bolstered by the #MeToo movement – is dismantled as quickly as it’s established. Those who insist we ‘believe’ women are often the first to throw stones, with the success and popularity of a female star often a tool with which to tear her down.

As Sarah Manavis of the Guardian says, ‘In spite of high cultural salience of supposedly feminist politics, a modern iteration of an age-old standard persists: that a man can do almost anything, but as long as a woman has done an inch of wrong, she will be the one that people – eagerly, gleefully – want to watch burn.’

It’s worth considering whether, had the New York Times not provided such detailed evidence to back Lively’s claims, she would have been listened to at all.

And why is it that women often need such extensive evidence of their mistreatment in order to be believed?

The myth that patriarchal society is slowly dismantling, allowing feminism to establish itself more firmly in the zeitgeist, is wiped out as soon as we choose to hate women who misstep. It’s as if we’re waiting for a reason to hate those who have wealth, power, beauty, support – looking for any signs of weakness with which to topple and tear them apart.

I dare say the same is not the case for most men.