A severely underreported humanitarian disaster is displacing millions and leaving many more without food.

Yemen, one of Africa’s poorest nations, is currently being devastated by a civil war that’s been raging since 2015. Five years of conflict has plunged the country into one of the world’s gravest humanitarian crises. As multiple factions backed by complex webs of external powers ravage the land, leading to the displacement of more than 3.65 million people and the probable deaths of over 100,000. The country is on the brink of famine and is now experiencing the worst cholera outbreak since records began. Yet, the western media is looking the other way.

In a west at peace with war, we’ve come to pick and choose the conflict that interests us most. We prefer to peer at states that exist on the fringes of democracy – Israel, Venezuela – and champion their attempts to push through to the ‘light’. But pertaining to states that exist outside of the liberal international order, we’re usually less interested.

One reason for this is that geopolitics in the East, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, is very complicated. The Yemen Crisis particularly so, with sectarian, bilateral, and global as well as civil interests playing themselves out in this relatively small theatre of war. But this complexity shouldn’t blind us to human cost of conflict, and the only way that peace has a chance is with the world’s collective attention.

What’s Happening?

The Yemen crisis has its roots in the 2011-12 Arab Spring uprisings, when the President that had led Yemen for 33 years, Ali Abdullah Saleh, was overthrown. During the Arab Spring, many countries throughout the MENA region toppled their governments in favour of democratic regimes. Whilst this was relatively successful in some places, like Egypt, in other places, most notably Yemen and Syria, the uprisings began an unstoppable domino effect still felt today.

After his deposition, former President Saleh turned over authority to his deputy, Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi. But Hadi was inheriting a powder keg of various socio-cultural tensions that Saleh’s toppling had ignited. Yemen, like most of the Arab region, had been plagued by jihadist insurgencies from groups such as Al-Qaeda and, increasingly, ISIL (ISIS) since the early 2000s. Additionally, the Southern region of the country was already trying to secede, there was rampant corruption and poverty, and much of the government remained loyal to Saleh. It was an unideal rap sheet.

A sectarian divide between two different cultural groups in Yemen was also rearing its head. Shia and Sunni Muslims are the two major groups, or denominations, of Islam in the world today. Whilst many Arab nations have a clear majority of one or the other of these groups (which often leads to problems of its own) Yemen is in the unusual position of being divided more or less in half.

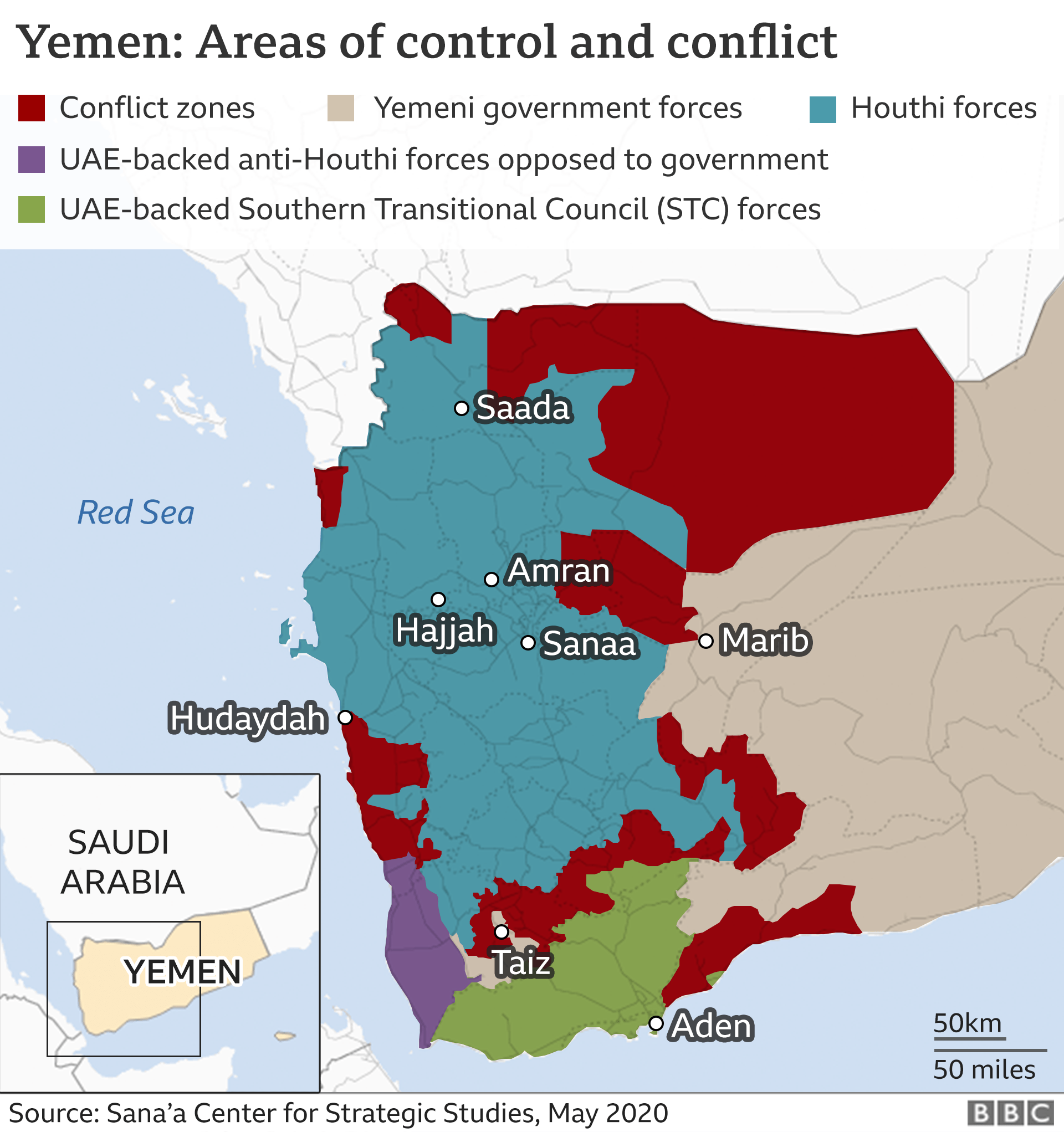

The Houthi movement (known formally as Ansar Allah), which champions Yemen’s Shia Muslim population and fought a series of rebellions against Saleh during the previous decade, took advantage of the new president’s weakness by taking control of their northern heartland of Saada province (where the Yemini capital is) and neighbouring areas.

They were supported by much of the Yemeni population, even Sunnis, who were disillusioned by the government’s transition.

The Houthis teamed up with security forces still loyal to Saleh and attempted to wrest control of the whole country, forcing President Hadi to flee to Saudi Arabia in March 2015, where he remains.

It was around this point that Saudi Arabia, considered to be the Sunni Capital of the Arab world and a direct neighbour of Yemen, decided to get involved. Saudi Arabia has long been in something of a cold war with the Middle East’s ‘Shia capital’ Iran, and strongly suspected that the Houthi fighters were backed by the Iranian military.

So, armed with this knowledge, Saudi Arabia and eight other majority Sunni states began an air campaign over Yemen aimed at defeating the Houthis, ending Iranian influence in Yemen, and restoring Hadi’s government.

They’re yet to achieve this aim. Four years later, and some mix of Yemeni government forces, Houthi forces, and the Saudi Arabian, Iranian, and now the Emirati military are locked in a stalemate. The influence of external forces can be felt more and more prevalently as time goes on, as ballistic missiles seemingly unconnected to Yemen are launched between Riyadh and Tehran that only result in more Yemini blockades.