The United States Agency for International Development (USAID), which represents a fundamental element of American soft power and is one of the most consequential development agencies in the world, is closing its doors.

While curtains never truly ‘fall’, there are flagging budget cuts, evolving US foreign policy objectives, and a rising tide of domestic investment that are all signaling a slow but inevitable decline. For Africa, it is the end of an era. But it could also end a long-overdue realization, a reckoning with aid dependency and a return to self-determined development.

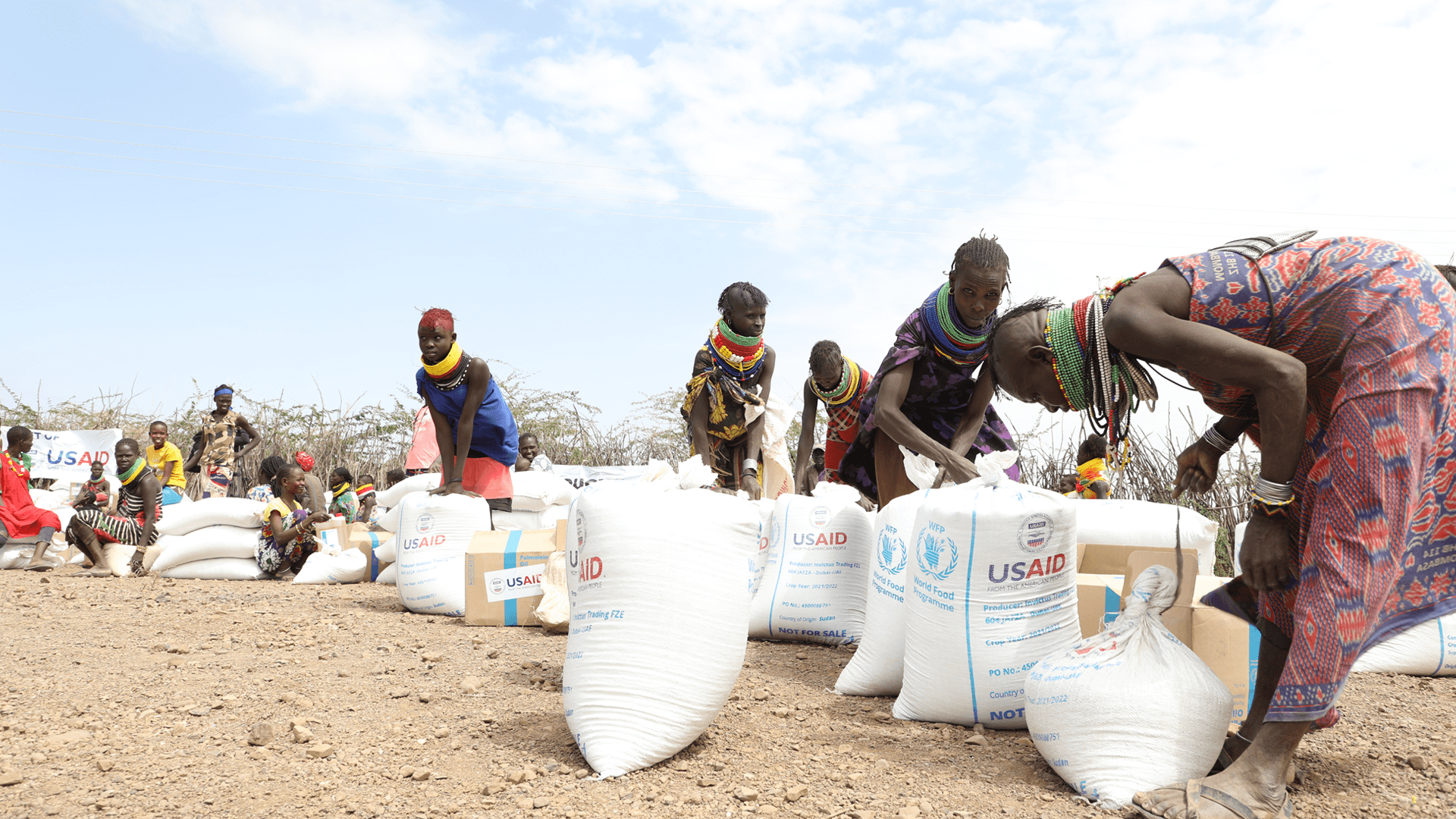

Since USAID was established in 1961, it has built its profile across the continent by funding health systems, food security, democracy building, and emergency humanitarian response. Millions of people have been helped, including those whose lives were significantly improved (like HIV treatment programs in Kenya to post-war reconstruction in South Sudan and everything in between).

Yet, the model has always been flawed. USAID has operated within a framework of strategic American interests, not purely African needs. It has often been paternalistic, and its funding has fluctuated based on changes in US administrations. The continent’s most vulnerable have too often been left at the mercy of foreign policies shaped thousands of miles away.

What does the end of USAID mean?

For one, African governments and institutions must finally grapple with the reality that external aid is not infinite, nor is it sustainable. While short-term shocks may follow, especially in health, education, and food relief, this is also a unique opportunity for African nations to rethink what development should look like when it’s homegrown.

The era of accountability and home-led solutions must begin.

Africa’s youth, the most digitally connected, politically aware generation in history, must push for better governance and transparency. Too many governments have relied on aid to plug holes caused by corruption, mismanagement, and a lack of political will.

The same enthusiasm that was seen in finding international funding should be applied to returning public services, investing in local agriculture, promoting technology uptake, and stimulating intra-African trade.