An unprecedented visa scheme between Tuvalu and Australia is garnering a huge response. Signed in 2023, the ‘neighbourly’ agreement allows Tuvaluans to live, work, and study in Australia – though most are moving against their will.

Three years ago at the world’s largest annual climate meeting COP27, Tuvalu’s foreign minister Simon Kofe announced that the country was making moves to preserve its culture in the metaverse.

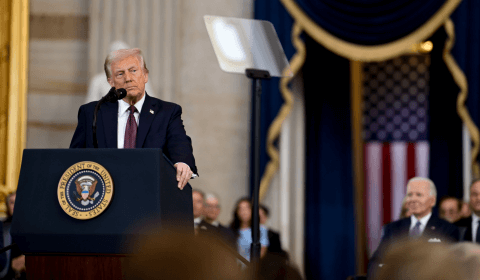

Standing behind a podium on the beach, Kofe was knee-deep in seawater that, in previous years, hadn’t lapped so far up the shoreline. It was stark reminder that, for some, the threat of climate change isn’t theoretical or abstract. It is evident right now.

Recognising the vulnerability of Tuvalu’s small population of around 11,000 people, officials from Australia and Tuvalu signed an agreement called the Falepili Union. It provides Tuvaluans the opportunity to live, work, and study in Australia.

The aim is to provide a safe haven for the Pacific islanders, as sea levels rise and encroach rapidly on their home. Successful applicants will have access to Australian education, health, and key income and family support on arrival.

On the 16th of June, a ballot for these visas opened. More than 1,120 primary registrations were received by Australia’s Department of Home Affairs, accounting for 4,052 people once family members of the primary applicant are included.

The problem is, only 280 visas are set to be granted by the Australian government each year.