In a recent study, researchers found that halving meat and dairy consumption could have a greater impact on cutting nitrogen pollution than foregoing animal products altogether.

Last year, it was revealed that the agriculture industry is responsible for about a quarter of our total greenhouse gas emissions, the main contributor being livestock and fisheries.

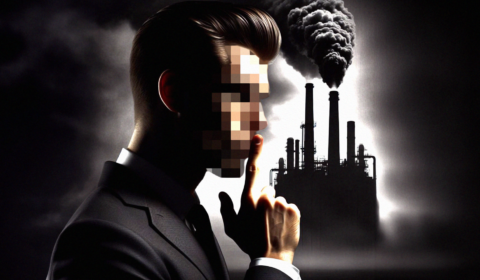

Yet although the drastic environmental impact of meat and dairy production has been at the forefront of the climate conversation for some time now, little has been done to address it – at least from a top down level, that is.

Most often, the solutions posed are targeted towards the individual, encouraging consumers to ‘give Veganuary a go’ or experiment with Meat Free Mondays.

For this reason – and in light of findings that cutting meat and dairy products from our diets could reduce our personal carbon footprints by up to 73 per cent – many deem veganism a silver bullet in the face of the ongoing ecological emergency.

Amid recent reports that fake meat sales are plummeting and the coinciding reignition of the ‘plant-based fad’ debate, however, people have started questioning whether replacing the dearth or meat and dairy in the average person’s diet with substitutes is truly a sure-fire way to fight the climate crisis.

And according to a new study for the United Nations (UN), they may well be onto something. As researchers uncovered, a ‘demitarian’ diet, which involves halving meat and dairy consumption rather than foregoing animal products altogether, is actually more effective at cutting nitrogen pollution than veganism.

But why nitrogen? On a regular basis, information regarding the agriculture industry’s contribution to global warming focuses on the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) emitted during the process of getting a single piece of steak to the dinner table.

However, scientists and world leaders have recently begun pointing to nitrogen as the ‘lowest hanging fruit’ in the fight to prevent further temperature increases, referencing the fact that it’s heavily concentrated on livestock farms, where animal manure is stored and treated in great quantities.