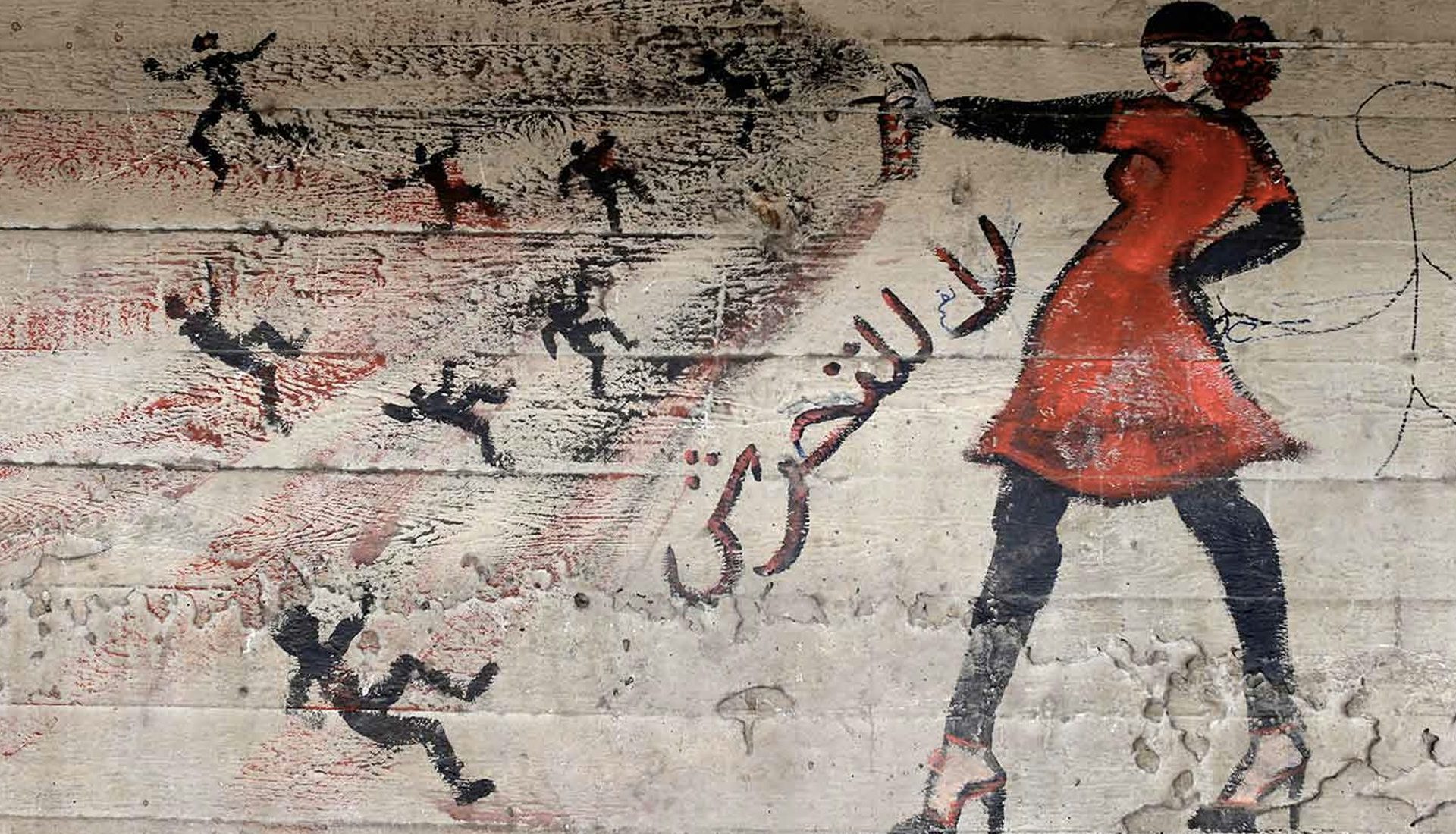

Egyptian women are still fighting for their freedom via social media, but the cost is terrible.

Social media continues to bring both justice and persecution to Egyptian women, as a number of lukewarm proto-feminist decisions by the Egyptian courts have failed to quash the nation’s ‘me too’ movement.

In response to a wave of protests that began circulating online in May, which saw women use TikTok to publicly speak out about their experiences of sexual assault and challenge modesty customs, the nation’s authorities have made scant concessions to women’s rights.

A TikTok posted by Aya Khamees, taken in the immediate aftermath of a violent rape at a party, was the catalyst of a movement that seemed to burst forth from the women of Egypt this summer, leading to mostly digital protests against a complete lack of gender equality before the law.

Khamees recently left a three-month rehabilitation program in the wake of her attack. Her story is a perfect microcosm of the kind of tepid justice social media is helping Egyptian women receive.

Khamees was arrested, along with her rapist and the other party guests, three days after her video went viral, which sees her covered in bruises and cuts and in obvious distress. She was charged with prostitution, drug use, and violating a crime recently added to Egypt’s penal code: violation of family values.

But as the TikTok continued to spread internally and beyond Egypt’s borders, a hashtag campaign arose demanding Khamees’ release. Eventually her charges were dropped on the provision that she complete a rehabilitation program.

Though curtailing charges against a rape victim is a pathetic justice, Khamees’ exoneration continues to be one of the sole bright spots in the campaign for freedom Egypt’s women are now waging.

In July, dozens of women went public with accusations in a serial assault case, leading to the arrest and prosecution of multiple rapist Ahmed Bassam Zaki at his home in an upmarket suburb of Cairo. In another high-profile case, a woman testified against a group of wealthy young businessmen, accusing them of gang-raping her years ago in a five-star hotel.

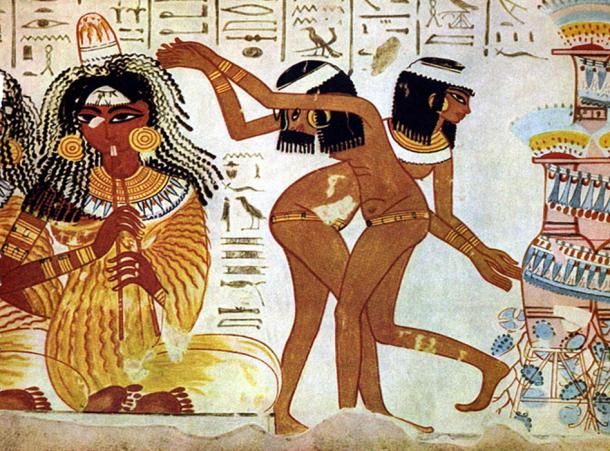

Seeing these unprecedented victories, hundreds of reports poured into the National Council for Women with accusations of assaults. The groundswells of revolutionary progress had been brewing in Egypt ever since the Arab Spring uprisings, and feminist activists were quietly stoking fires online for years. Social media was one of the few remaining precincts of free expression under the rule of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, whose government tightly controls traditional media like television and newspapers.

Unfortunately, however, that voice can only project so far. Hitting back against the culture war fermenting on platforms like TikTok, the Egyptian court made a series of arrests throughout July and August of female TikTok stars on charges of ‘violating family values’. Nine women were detained and at least seven are now serving out sentences in prison.

Clearly, these overtures towards justice are reluctant concessions rather than genuine indications of genuine reform, with courting the law’s protection seemingly predicated on class. Whilst the hordes of women who accused the wealthy Ahmed Bassam Zaki of assault through the dedicated Instagram page @assaultpolice were mostly upper class, the ‘Tiktok girls’ (as they’ve come to be known) were from working-or middle-class backgrounds.

Traditionally, the working class in Egypt uphold a more socially conservative, patriarchal vanguard state that heavily polices women, and have far less clout with the law.

https://twitter.com/Historicalpoli/status/1288219441323552779