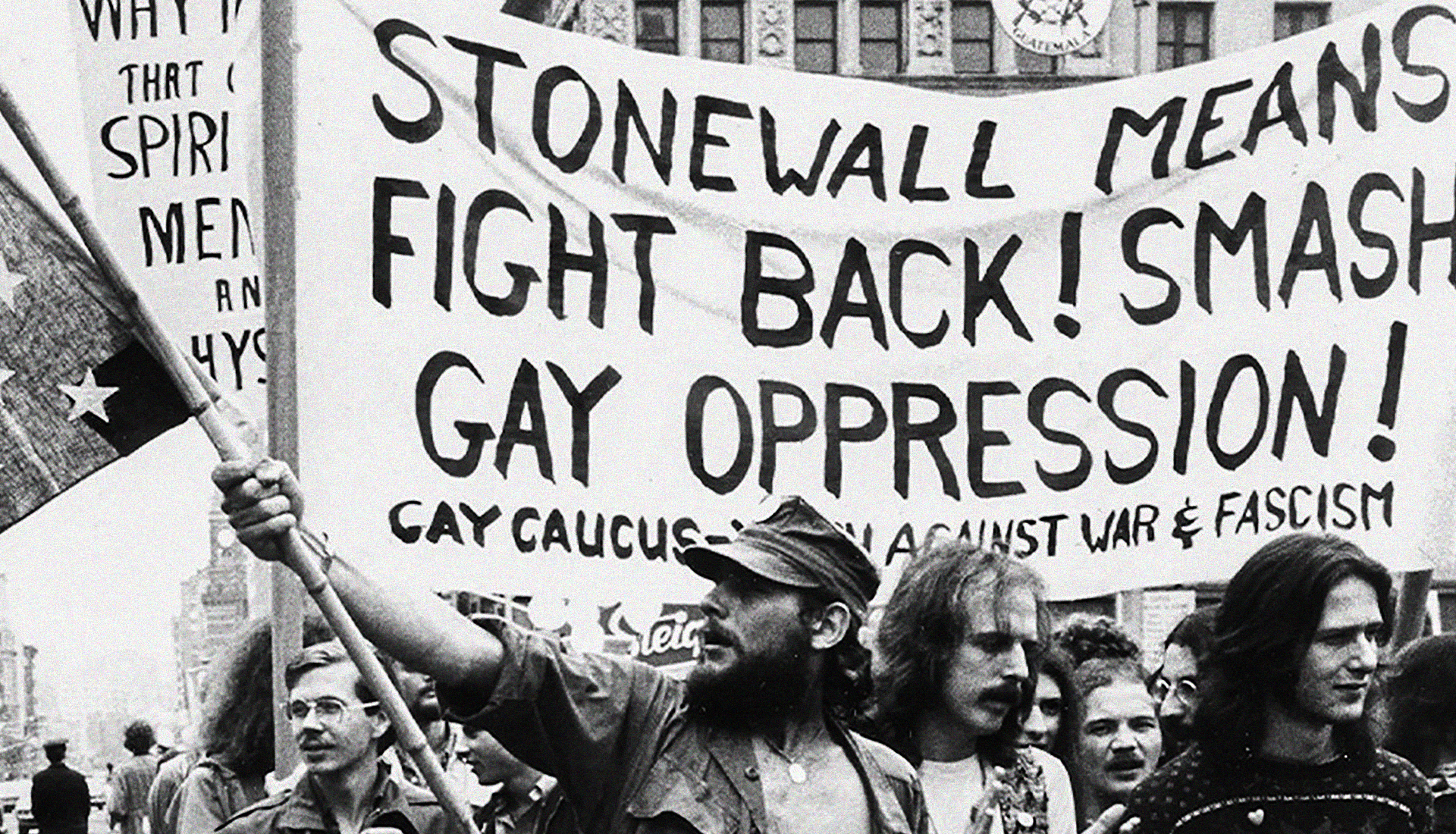

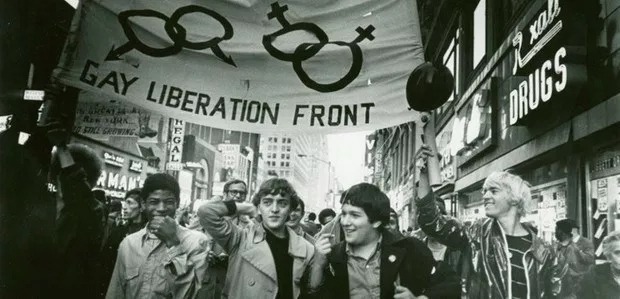

We take a look back at the Stonewall riots and what they meant for the LGBT+ community.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the 1969 Stonewall Riots. This monumental event is well remembered, with several books, a number of films, radio documentaries, and more dedicated to its historical importance.

But, even though we commemorate it each year during Pride Month, with gay pride marches throughout June serving as a direct call-back to the event, I’ve found that many Gen Zers have never actually learned about Stonewall. Considering that a defining tenant of our generation is to uplift the LGBT+ members of our community, it’s important to remember the ancestors who fought for their right to not only speak out but come out back when oppression was rife.

So, buckle in people, this is a history lesson.

Some context

The perception that queer people ‘had it hard’ before Stonewall is often accompanied by the belief that the further one goes back in time, the worse the oppression was. If it was bad in the 1960s, imagine the 20s, or the 1600s! But historians have shown that this is far from the case. Whilst the prevalence of sodomy laws during colonial times is often thought to have been aimed at gay people, in fact more often charges were filed against those who had sex with animals or forced themselves on women.

It’s widely reported that a thriving gay community existed in New York at the beginning of the 20th century, with gay visibility in plays, films, and subculture in general being common. It even had a name (albeit politically incorrect by today’s standards): ‘the pansy craze’. However, a backlash against queer people began during the depression era that worsened in the wake of WWII. After so much social turmoil there was a call for a return to ‘traditional’ values in the US. The hysteria aimed at gay people was fed by the Cold War in the 50s, with the fear of communist infiltration engendering a corresponding desire for American men to be ‘tougher’ in defence of western values.

Sex offender laws were revised in the 40s and 50s to stiffen penalties against homosexuals and to allow their involuntary commitment to mental asylums. Once these laws were institutionalised, it became common to subject gay communities to ‘cures’ and ‘conversion’ operations including chemical and electric shock treatments, castration, and lobotomy.

In sum, it really sucked to be a member of the LGBT+ community in the mid-20th century. This was a reality for most of the West; however, it was particularly prevalent in the US where Stonewall occurred.

Build up to the Riots

In the NYC of the 60s it was generally illegal for known homosexuals to congregate in large groups, dance with members of the same sex, or dress in clothing that didn’t match their assigned gender. These activities were driven underground into bars and nightclubs.

Greenwich village became known as a hotspot for Mafia owned bars that permitted ‘gay activity’ purely based on its profitability. Whilst police raids on such institutions were common, these crime families were often tipped off regarding upcoming raids by corrupt officers and kept relations sweet by paying off the police heftily. Knowing that these gay bars would be lucrative for them, the NYPD unofficially allowed the practice of crime funded LGBT+ establishments to continue.

Stonewall, operated by the Genovese crime family, was one of the largest of these venues. It existed in corrupt symbiosis with the NYPD for many years until the latter caught wind that the bar owners were blackmailing prominent figures who frequented the bar, extending their profits. In one of the pettiest moves in history, officers decided to shut the bar down after seeing none of the bribe profits being directed toward them. This is where things get interesting.

The Riots

At around 1:30am on June 28th, 1969, police raided the Stonewall bar. The mafia hadn’t been tipped off about the raid, which turned out to be a particularly venomous one. Standard procedure for a raid was to order patrons to line up and present ID, however this time officers were allegedly rough in their handling of partygoers and touched female clients inappropriately.

Despite numerous first-person accounts, it’s hard to find a specific catalyst for what happened next. Tension had been building so long in the community that a tipping point had clearly been reached, even if it wasn’t detectable to the police. The law had condemned LGBT+ people as criminals, medicine had declared them insane, and the church had branded them sinners. The constant assault on lesbians and gay men during the 50s and 60s meant that it was impossible to imagine a positive gay identity, let along a gay culture. The kicker? Any and all attempts at combatting this oppression by members of the community had only succeeded in relegating them further into the shadows.

On June 28th, something snapped. People in the line-up refused to produce identification. Transvestites refused to take off their female clothing. The police began shepherding partygoers outside and making public arrests. Instead of disbanding, however, the patrons milled about outside, amassing even more onlookers.

Attendee Michael Fader explains ‘it wasn’t anything tangible anybody said… it was just kind of like everything over the years had come to a head on that one particular night in the one particular place… It was like the last straw.’

According to onlookers, the crowd turned violent. The news that the police were there to collect bribe money spread through the throng, and they began throwing coins at the police cars. They grabbed bricks from a nearby construction site and commenced trashing the Stonewall itself. Garbage cans, garbage, bottles, rocks, and bricks were hurled at the building, breaking the windows. Witnesses attest that ‘flame queens’, hustlers, and gay ‘street kids’—the most outcast people in the gay community—were responsible for the first volley of projectiles, as well as the uprooting of a parking meter used as a battering ram on the doors of the Stonewall Inn.

When the situation escalated, police called in the Tactical Patrol Force (essentially the riot squad), however the LGBT+ mob had grown to overwhelming proportions. Bob Kohler, who was walking his dog on the night of Stonewall, recalled ‘the cops were humiliated. They never, ever happened. They were angrier that I guess they had ever been, because everybody else had rioted… but the fairies were not supposed to riot…’