Despite German suspicions of Ukrainian involvement in the pipeline blasts, Europe’s fear of a potential security breach by Russia keeps its support for Ukraine intact.

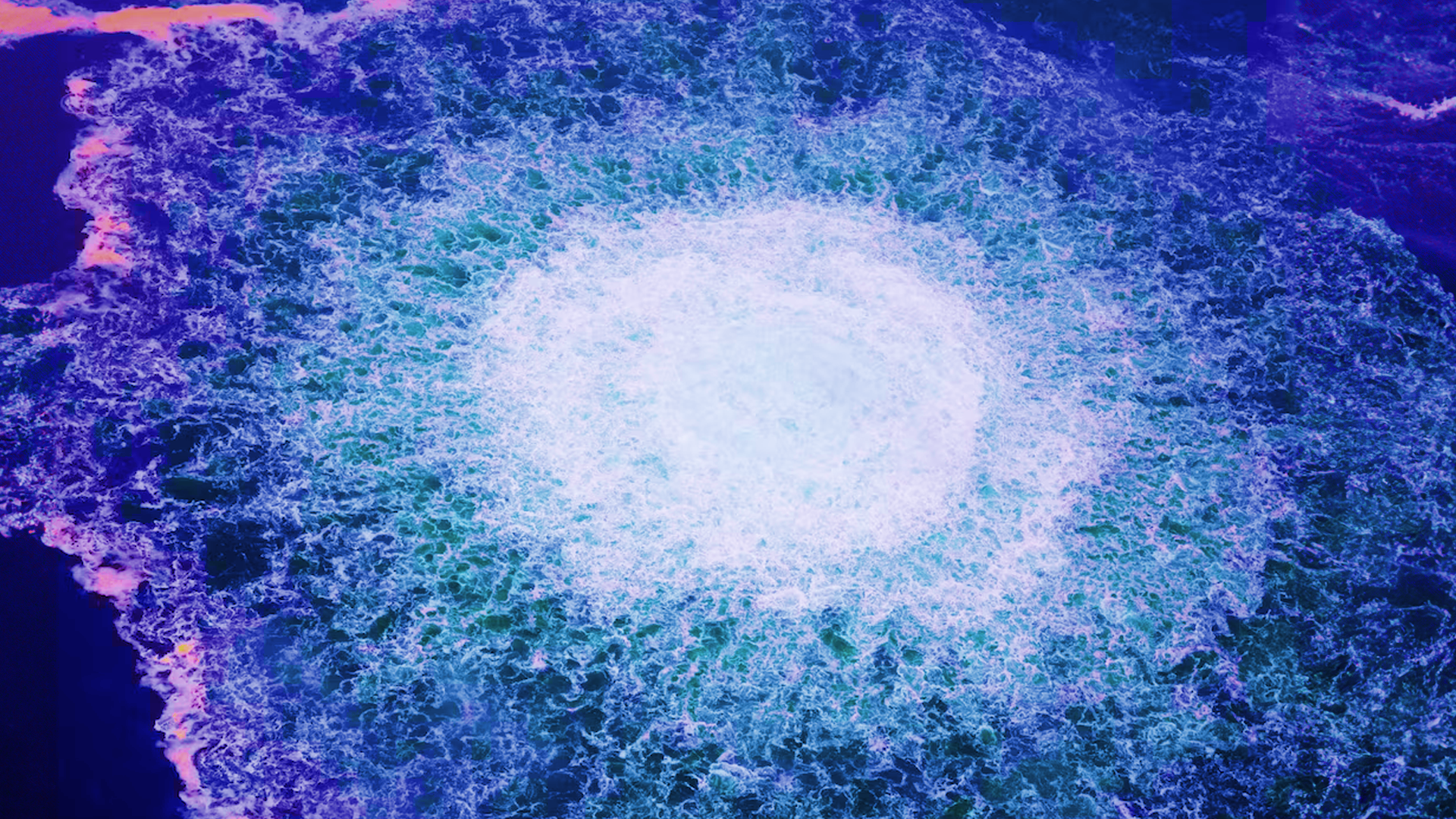

Three years ago, in September 2022, powerful explosions in the Baltic Sea shocked Europe.

Seismological data indicated that the blasts were consistent with a large underwater bomb, later confirmed when shrapnel was discovered at the epicenter. The attacks targeted the Nord Stream pipelines, a vital energy link between Russia and Western Europe. Earlier this year, an official investigative report made explosive accusations that many feared could shift the course of the Russia-Ukraine war.

The Nord Stream twin pipelines were built by Nord Stream AG, a company majority-owned by Russia’s state-controlled Gazprom, with support from major European energy firms including Uniper, Wintershall Dea, Shell, Engie, and OMV. Designed to transport natural gas directly from Russia to Germany via the Baltic Sea, the pipelines bypassed transit countries such as Ukraine and Poland, lowering costs while increasing Moscow’s leverage over Europe’s energy supply.

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, gas flows through Nord Stream 1 were halted, and Germany suspended the use of Nord Stream 2. Later that year, the September explosions destroyed three of the four lines, releasing up to 485,000 tonnes of methane, one of the largest human-caused leaks in history.

Investigation updates

Following the explosions, Denmark and Sweden launched investigations since the incident occurred within their Exclusive Economic Zones, as did Germany, being the main recipient of the gas and key stakeholder. Sweden later ended its probe, citing lack of jurisdiction, and Denmark closed its case due to insufficient evidence. Germany, driven by national energy security concerns, continues to pursue the investigation.

A few months ago, German authorities issued arrest warrants for suspects who were identified to be Ukrainian nationals in connection with the explosions. These individuals include, Volodymyr Zhuravlev, a diver arrested in Poland and a former Ukrainian intelligence officer, Serhiy Kuznetsov, arrested in Italy.

Some reports have even linked the operation to a unit allegedly supervised by Valerii Zaluzhnyi, Ukraine’s previous Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, though Ukrainian officials have officially denied any state involvement.

As such, new revelations have sparked concerns that Europe’s support for Ukraine could weaken, especially with the never-ending hostility from Russia’s side. If Ukrainian operatives were caught attacking critical European infrastructure, it could fuel public pressure to reconsider support for Ukraine, especially with all the financial aid being spent on them. Yet, this might not be the case, politically speaking.