Extinction Rebellion have achieved their first aim: attracting attention. Now it might be time get into the finer details.

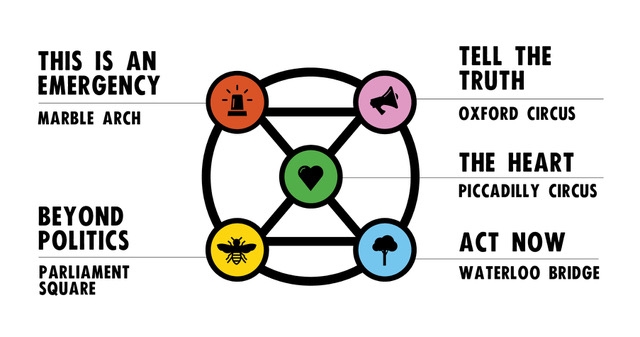

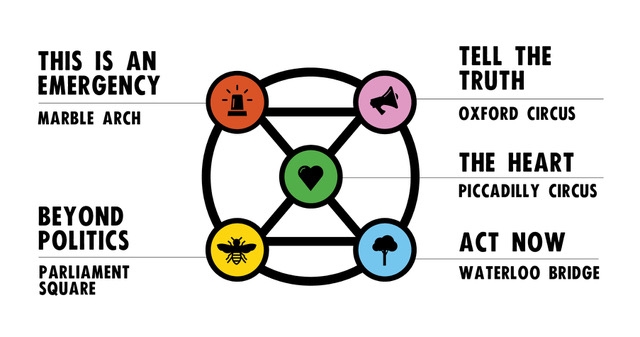

One of XRs key rallying cries is ‘beyond politics.’ Whether the group’s eschewing of party politics was its plan from the beginning or something that germinated along with its growth is unclear, but the theory behind it makes sense.

XR placing themselves beyond the bounds of politics is, ironically, a political statement. They reject party allegiances because they believe that climate change is an issue too important to be embroiled in the red tape and petty infighting of traditional partisanship. The mantra urges politicians to look beyond the legislative complications of climate preservation to humanity’s future.

As a war cry it was initially fitting. Whilst climate change policy is complicated, establishing the need for it shouldn’t be. XR’s initial goal was to call attention to the big picture and establish climate change as not a political but a human issue that simply demanded the attention of politics.

And as far as this aim goes, they seem to have done a pretty good job. Their April protests were a resounding success. Together with the school climate strikes and the BBC’s harrowing Attenborough documentaries they created a surge in public concern regarding the environment. According to this government census, the climate crisis is now considered by UK citizens as one of their top five major concerns. For Gen Z and millennials, it’s top three.

It’s no coincidence that soon after XR started gaining widespread support from the British public, the UK government legislated a goal of net-zero greenhouse emissions by 2050, and Labour announced movement towards a much more ambitious target – net-zero by 2030.

Extinction Rebellion’s rise and influence have undoubtedly been extraordinary. They’ve galvanised people young and old and across party lines (beyond politics indeed) to devote themselves to disruptive and non-violent disobedience in service of one simple goal – making the public voice so loud that governments were forced to act. In fewer than 12 months, XR has become the fastest-growing environmental organisation in the world.

But, herein lies the rub. The way that politics works, ‘action’ doesn’t necessarily carry connotations of… well… action. Politicians and parties’ response to the effective pressure put on them by XR and other lobbyists was merely a promise of action.

Take the government’s net-zero law for example. It would just about make the UK compliant with the Paris agreement’s goal of avoiding catastrophic temperature rises – which is most definitely better than nothing.

Thing is, the government wasn’t even on course to meet its old, weaker carbon targets involving less cohesive operations such as ‘banning petrol cars by 2040’. Certainly, at time of writing we’re nowhere near meeting net-zero come 2050.

Moreover, whilst Corbyn’s notion at the recent Labour Party conference to meet net-zero by 2030 is, in theory, close to XR’s own demand, it’s pointless to give ecological credit to words. I could promise you a beach house if you cooked me lunch, doesn’t mean I’m going to cough up. In fact, until I show you that I have the means and the ability to buy you a beach house I wouldn’t advise entering into that trade at all.

Labour have yet to unveil an actual plan showing how they will reach this ambitious yet necessary climate goal. Doing so would necessarily mean throwing the middle finger to union funders and lobbyists that have previously supported labour by retracting plans to build a new runway at Heathrow, amongst other things. It’s something Labour should absolutely have the guts to execute, but they’re yet to prove that they do.

Unfortunately, the only way to confirm that governments mean what they say is to demand legislation that outlines a process of implementation. And that, my friends, is what I like to call politics.