‘Polish Stonewall’ is an admirable but doomed shout into the abyss for a region already engulfed by fascism.

At this moment in time, the Polish LGBT+ community are fighting their newly elected government for the right to be. ‘Polish Stonewall’ is part of a pushback by minorities and Eastern European youth against the region’s recent backslide into nationalism. It’s heartening to see that human rights as we understand them in the democratic world still has a safe house in the Eastern Bloc, but it is undoubtedly a fugitive.

‘Poland is not East or West. Poland is at the center of European civilization’ – Ronald Reagan

At the beginning of August, our newsfeeds, now functioning as constant tickers of worldwide unrest, filled with protest images from Poland. The stills of youths marching the streets of Warsaw, masks on, rainbow signs clutched in fists held high, were of course intermingled with their necessary ideological opposite images of violent police repression. Clearly a stand was being taken.

TRANS AND QUEER

STAND WITHOUT FEARPhotos from today's protest at the Polish Consulate in New York city.#MuremZaMargot #MuremZaStopBzdurom#PolishStonewall pic.twitter.com/dxMFlVe9Bl

— Wiktor Dynarski (@wdynarski) August 9, 2020

Polish Stonewall was ostensibly instigated by the mid-July arrest of Margot Szutowicz, co-founder of queer collective Stop Bzdurom [‘Stop Bullshit’], for ‘promoting false anti-LGBT propaganda and assaulting a pro-life demonstrator’ on 27th June. But the context is much wider than that.

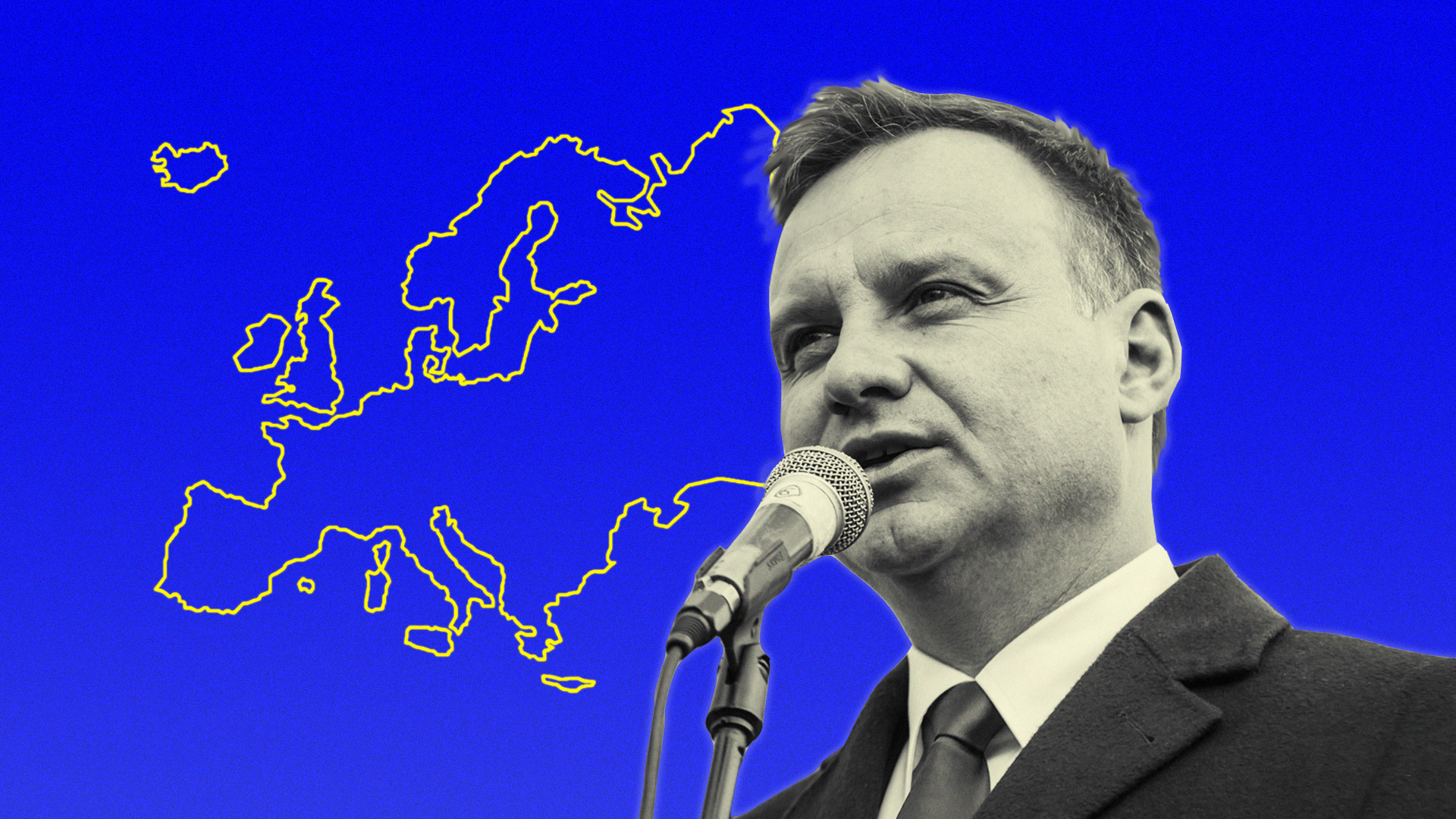

Poland is experiencing the backlash from its recent Presidential election’s culture war. July saw incumbent Andrzej Duda and his Law and Justice party (PiS) re-elected on a platform of conservative national policies including Euroscepticism, opposition to LGBT+ rights, and justice policies that threaten democracy. Feeding anti-gay rhetoric to the masses and pursuing a paranoid politics that divides Poland into ‘true’ Poles and Eurotrash turned what could have been a landslide victory into a close shave, but Duda still walked away with 51% of the vote.

Poland is once again ruled by a man who has called LGBT+ rights an ‘ideology more destructive than communism’, has signed a ‘Family Charter’ that pledges to prevent gay marriage and adoption, and is considering an anti ‘gay propaganda’ law similar to Russia’s.

As it cosies up to the bosom of Russian moral absolutism, Poland follows in the footsteps of Hungary. There, Prime Minister Viktor Órban is less pulling his country down the tunnel of despotism than striding in step with its majority. Órban’s 10-year reign (and counting) is a nationalist dog whistle to ‘new’ old values: the fatherland, the Christian faith, family. His government has relentlessly attacked Hungarian democracy such that Freedom House maintains, given the government’s tight control over the media and independent institutions, Hungary can no longer be considered a democracy.

During the COVID-19 crisis, Órban took on emergency powers that allow him to rule by decree which he is unlikely to give up with the pandemic’s ebb. He is consistently threatening the sovereignty of surrounding states, issuing passports to ethnic Hungarians outside the country’s borders and thus championing an ‘idea’ of nation over the states the EU recognises.

The plight of the Hungarian LGBT+ population continues to worsen – predictably, Órban abused his self-granted power during the pandemic to push a gender immutability law through parliament, abolishing trans rights.

With these lurches in international sentiment, the concept of Europe qua the world is being redefined.

‘One strength of the communist system of the East is that it has some of the character of a religion and inspires the emotions of a religion’ – Albert Einstein

Similar far-right ideologies are popping up along the Eastern bloc like whack-a-mole. Counter-movements to the relatively open societies of Western Europe are created with every new far-right election victory.

The idea of this conservatism is to grant ‘the nation’ priority in a borderless, globalised existence. Duda, Órban, and their contemporaries are attempting to simplify an increasingly complicated world that is also collectively regarded as threatening. Both men make no bones about openly opposing democratic styles of government, with Órban christening his Hungary an ‘illiberal state’.

The broad direction the country of Poland is headed can clearly be seen through public opinion on immigration. ‘We don’t want terrorists here’, a Polish grandmother tells Guardian journalist Adam Leszczyński. ‘Have you seen what they’re doing in the west?’

The novel threats immigrants supposedly bring with them according to anti-immigration stalwarts – what they’re ‘doing’ to the west – usually involves some form of moral and anti-Christian oppression. Poles don’t want Islam diluting the ‘purity’ of their culture – subjugating their women, radicalising their sons.

This Islamophobia, of course, overlooks the egregious acts of domestic terrorism committed by what’s now the country’s centre. Stripping trans people of their identity, slashing welfare benefits, denying the existence of ethnic minorities, and encouraging police militancy, illicit the exact kind of lawless brutality Poles suspect of far Eastern arrivals, merely tying it in a nationalist bow.

Queer DJ Avtomat describes to i-D his experience during the protests in Warsaw of being bundled roughly into police vans, driven recklessly around the city with no information and no seatbelts, and laughed at by officers who directed homophobic slurs at him and his companions. Their lawful entitlements – to access medication whilst incarcerated, to be given a reason for incarceration or told if they were under arrest, to inform their family or lawyer – were denied in clear violation of the EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights.

Queer communities are being written off en mass in the country as safe havens for paedophiles. Around 100 municipalities have declared themselves ‘LGBT-free zones’. Ministers are comparing queer people with Nazis. And, though solidarity marches with the Polish protesters are appearing the world over, in New York, London, and even Hungary itself, it’s easy to predict how good intentions and rainbow flags will fair against such an overwhelming tide of fascism.