Did all those millions of people who took to the street last week to #strikeforclimateaction actually make a difference?

As someone who recently stopped eating meat, who only ever takes public transport, and who habitually yells at my co-workers that crisp packets can be recycled, I’m familiar with the feeling that my attempts to alleviate greenhouse emissions are pointless.

It’s hard to believe that your going for a lentil bake at Christmas over the delicious roast lamb your Aunt makes every year is going to make any difference in the face of big corporations and big government conspiring to mutually let one another off the hook for crimes against social justice.

And, as much as I hate to say it, we’re not wrong to feel that way. In the grand scheme of things, no, your adoption of veganism is not going to have a marketable difference on whether or not the world is able to reach the targets of the Paris Agreement.

It’s a dispiriting conclusion and begs an obvious question: why bother?

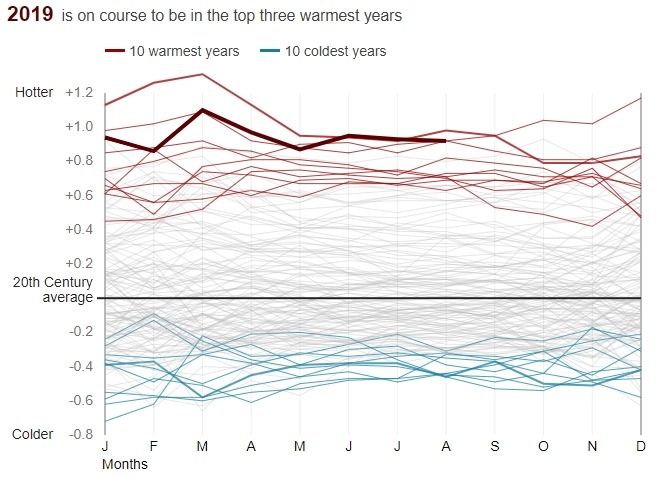

Passivity is the route that many choose to take in the face of climate change. The destructive impacts of the climate crisis are now following the trajectory of that economics maxim as horrors long predicted by scientists are becoming realities.

More destructive category five hurricanes are developing, monster fires ignite and burn on every continent but Antarctica, ice is melting in large amounts there and in Greenland, and rising sea-levels now threaten low-lying cities and island nations. But none of this is your fault, and it’s not like you work for big oil and are directly contributing to the problem, so bore off and let you watch Holby City in peace. You didn’t light the fire (it was always burning), so it shouldn’t be your job to put it out.

Worse still than these passive onlookers are what I like to call ‘climate nihilists’. Those who seem to take pleasure in pointing out the apparent hypocrisy of vegans with iPhones (don’t you know the gold parts of your phone were made in inhumane factories in China that produce XXX carbon emissions per individual part?!).

These people use the hopelessness of individual action as an argument to do nothing, but at least, they argue, it’s an informed doing of nothing. Think of their attitude as equivalent to the shrinking but still prevalent subsection of the vegan community who insist that vegetarians and all those who don’t go the full hog (pardon the pun) are morally inconsistent, thereby encouraging these people to go back to meat consumption out of spite.

Nobody was waiting for a vegan bloody sausage, you PC-ravaged clowns. https://t.co/QEiqG9qx2G

— Piers Morgan (@piersmorgan) January 2, 2019

Whilst it’s true that individual action in the face of a global problem is close to useless, it’s also the only morally justifiable course of action available to us.

Thinking of the climate issue like the trolley problem. Generations before us have seen our path of destruction hurtling towards a family of four, and not acted. Doing nothing is generally the surest way to avoid blame for an undesirable outcome.

Gen Z, on the other hand, have decided that inaction is a moral decision of its own. It’s now gotten to the point that simply living in a big city in the 21st century is actively harming the environment through an excess of CO2 emissions. And changing the course of the trolley won’t have any adverse effects besides harming big industries and making a lot of government officials fall out with heavy pocketed donors.

So, now imagine the trolley problem, but on your current set of tracks there’s a family of four and on the other there’s a giant pile of money. Do you pull the lever?

Of course you do.