The surprise hit for HBO Max has just been renewed for a second season – but its success highlights the age-old question of who gets to tell queer stories.

Heated Rivalry, a show based on Rachel Reid’s novel about two ice hockey players who fall in love, was only meant to air on Canadian streaming service Crave. The explicit sex scenes and niche plotting weren’t likely to draw in huge numbers – but shortly after airing the series exploded in popularity to such an extent that HBO Max picked it up shortly thereafter.

By the time the 5th episode aired on Friday, Heated Rivalry had secured top spot on the streaming service and drawn in its biggest numbers of the year. The phenomenon of horny gay hockey players is one few understand – Rachel Reid didn’t think anyone would read her novel when she first started writing it, and now ice hockey-themed romance is one of the biggest recent literary trends.

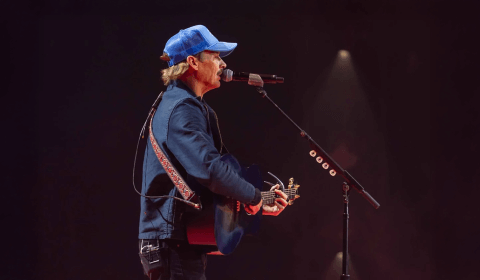

Fan edits, recaps, and viral memes have flooded the internet and pushed actors Hudson Williams and Connor Storrie into the limelight. But despite this overnight success, the show hasn’t been without its controversies.

As is often the case when queer media finds mainstream popularity, age-old debates around who gets to tell these stories inevitably crop up. But these questions have long proved damaging, particularly to closeted creatives.

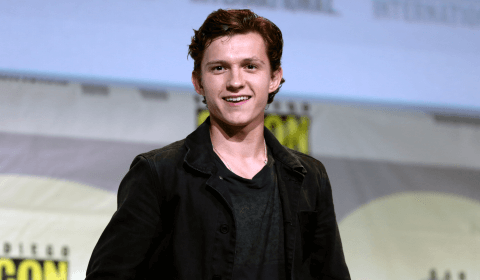

At the centre of the criticism are the show’s two lead stars, Williams and Storrie. Both caught heat from I Love LA actor Jordan Firstman last week, who told Vulture that the intimacy depicted on screen wasn’t accurate to authentic gay experiences. He then went on to say that both Williams and Storrie should out themselves if they are gay – alluding to both actors’ ostensibly heterosexual identity (neither have disclosed their sexual orientation publically).

In response to Williams’ and Storrie’s displays of close friendship – including a matching ‘sex sells’ tattoo – Firstman said ‘I don’t respect you because you care too much about your career and what’s going to happen if people think you’re gay.’ These comments feed into dangerous assumptions about those who depict queer characters, and suggest that telling these stories is a right reserved only for out, queer individuals.

Not only is this wholly dismissive of the creative process, but it places closeted creatives in a damaging position. Beneath the language of authenticity and accountability sits a deeply troubling implication: that queer stories are only valid when told by people who are publicly, visibly, and legibly queer – and that anyone who does not meet that threshold owes the public an explanation.