The African Union (AU) has launched a new ten-year educational plan. It covers the whole continent from 2025 to 2034 with the aim of rebuilding and transforming learning by means of innovation.

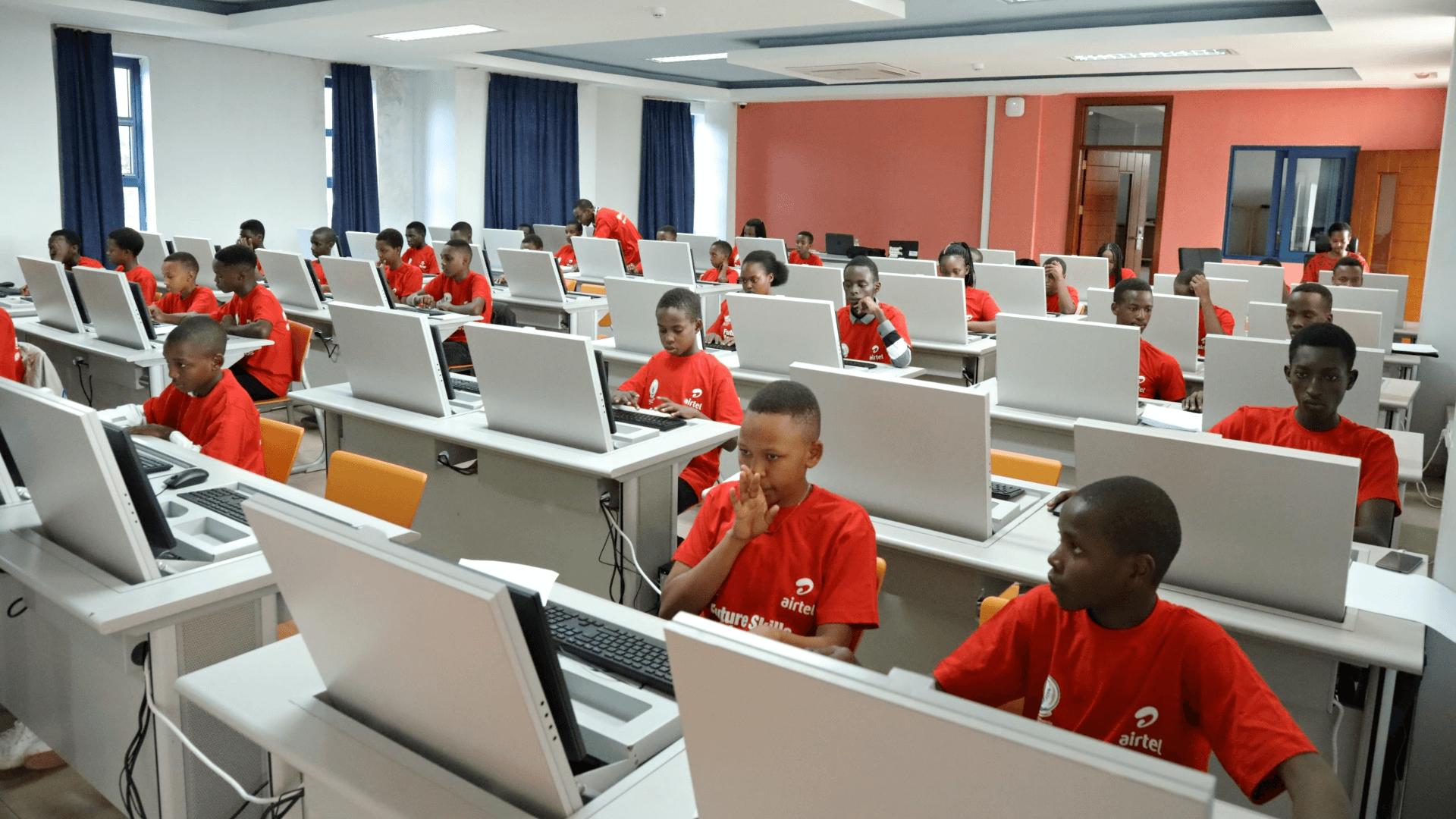

The AU plan aims to produce more qualified teachers, improving technology in the classrooms, closing gender divides, and equipping the youth with the skills that are in demand and suitable for the future jobs.

As exciting as it sounds, however, this education framework will confront the same challenges: poor funding, inequality, and governments that too frequently simplify their own commitments.

What is the plan?

The AU’s new framework, titled ‘Education for Transformation and Sustainable Development 2025–2034’, aims to overhaul Africa’s education systems by addressing five key areas. Teacher training and professional support, digital learning, gender equity and inclusion, STEM and innovation, and sustainable financing – which encourage governments to commit at least 20% of national budgets to education.

This initiative is introduced as the continent seeks an educational turnaround. Per the World Bank, 90% of sub-Saharan Africa’s children reach 10 without the ability to read or comprehend a simple text. This stat alone shows why reform can’t be postponed further.

With the youngest population globally, Africa comprises 70% of people under 30. Africa is projected to bear the brunt of the world’s youth population by 2050, with 1 in 3 youth globally, marking a significant demographic milestone. Yet, many of this population remains either uneducated or is receiving teaching of such poor quality that it is not useful for the highly technical, digital global job market.

The plan directly responds to the educational crisis spiral. It states that education forms the bedrock of all sustainable development transformations, economic durability, and creativity. More profoundly, the statement embodies the spirit of youth empowerment as it emphasizes that they, young Africans, are the ones to construct their destinies.

Launched today – The @_AfricanUnion Decade of Acceleration for Transformation of Education & Skills (2025-2034). A commitment towards Africa’s children to accelerate inclusive & equitable & quality education aligned to #Agenda2063 & #SDGs. #ForEveryChild pic.twitter.com/OXh3mFjwJg

— UNICEF Office to the African Union & ECA (@UNICEF_AUOffice) October 1, 2025

Across the continent’s schools, Gen Z is hungry for a new educational paradigm, driven by the imperative of preparing them for the global marketplace, as opposed to the traditional schooling. Many young Africans note that schooling remains old-fashioned, under-resourced, and disconnected from practical skills.

Countries such as Rwanda, Kenya, and Ghana have successfully initiated national digital learning programs and have established a classroom environment with tablets and digital curricula. Nigeria’s EdTech startups are providing other alternatives for out-of-school youth using mobile apps and artificial intelligence tutors.

But access remains pretty uneven. Electricity that is not reliable and internet that is of poor quality hinder the learning process of millions in rural areas. This, if not remedied, will witness the digital divide persist in marginalizing the most vulnerable students.

One of Africa’s biggest education challenges isn’t just infrastructure, it’s teachers. The AU estimates the continent will need 17 million additional teachers by 2030 to meet basic education needs. Many current teachers work underpaid, overstretched, and undertrained.

The plan includes calls for investment in teacher training and professional growth, including incentives to keep educators motivated. But this will require serious political will, and money.