In Kashmir, savoury pink tea is a staple. But outside the valley, it’s been rebranded into something sweeter, almost sparking a quiet identity crisis. Let’s unpack the history, evolution, and brewing debate over what makes nun chai truly Kashmiri (hint: it’s salt).

‘Bas bas! Main itna nahi kha paungi! (Enough, I won’t be able to eat so much)’ I protested in Urdu, watching in dismay as my delicate cup of nun chai – a pink, salty tea – was transformed into a vessel brimming with bakerkhani, a Kashmiri flatbread, layer upon layer added right before my eyes.

This, however, was not my first encounter with the art of Kashmiri hospitality – where refusal is futile, and finishing every last drop of tea is a testament to the bond shared with your hosts.

Taj aunty, my spirited neighbor, spoke not a word of Urdu, whilst my grasp of Kashmiri at the time was embarrassingly minimal. Yet, despite this linguistic barrier, we had built an unconventional, but sincere friendship.

My poor grasp of Kashmiri was our only choice, with the occasional help of one of her mischievous grandchildren, who served as interpreters when things got lost in translation.

I glanced at her grandchildren – several years younger than me – hoping they would come to my rescue. But, Taj aunty was undeterred, adding one piece of bread after another to my tea. At some point, it was no longer a beverage but a pink-looking stew that demanded to be eaten with a spoon rather than sipped.

The children, fully aware of my predicament, laughed gleefully for they knew, as did I, that there was no escape from this overwhelming display of affection.

And so, with no choice but to uphold the sanctity of her hospitality, I resigned myself to the task. To do otherwise would practically be an insult, and I was not about to risk spoiling the bond of friendship that we had recently developed.

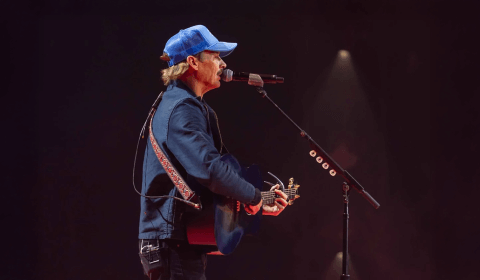

Caption: A cup of nun chai at the famous Srinagar cafe Chai Jaai (Kashmiri for ‘the Chai Place’)

It has been what seems like ages since that day, and I haven’t had such flavoursome nun chai since. Perhaps it is because outside Kashmir, it just does not taste the same.

Not everyone’s ‘cup of tea’

I have, however, come across nun chai’s distant cousin: the pink tea served in London.

Admittedly, I was quite surprised when I first saw it being served here because it is a drink that is particularly local to Indian-administered Kashmir, and I thought it was considerably unfamous outside the valley.

But the first time I tried it, something felt deeply wrong. It certainly had the familiar pink colour of nun chai, but the taste? Sweet, as if someone had taken the soul of Kashmir and drowned it in sugar.

Regardless, I kept my thoughts to myself for a long time, fully aware that people from neighboring regions to Indian-administered Kashmir add sugar to their pink tea – which is what I seemed to be drinking.

Salt vs sugar: such a minor difference, yet it holds the power to spark endless debates and even outright outrage (just ask any Kashmiri, they’ll be sure to tell you).

Tracing the history of nun chai

There are countless stories about the origins of nun chai in Kashmir, yet no definitive history exists.

One legend traces it to the Yarkand region of Turkestan, where tea is traditionally prepared with salt, milk, and butter – a rich and unusual combination. Another theory links its origins to Ladakh’s butter tea, or Gur-Gur chai, made with yak milk, butter, salt, and Tibetan tea leaves.

But what truly makes nun chai fascinating is not merely its debated origin, it’s the labour of love that goes into its preparation. Made by infusing gunpowder tea leaves and baking soda in water, it is brought to a boil and reduced multiple times until it develops a reddish hue – a concoction referred to as tueth in Kashmiri.

A meticulous and time-consuming process, nun chai is one of the rare teas in the world made using baking soda, a key ingredient that gives it its iconic pink hue.

@khoslaa I did not know pink tea existed 😭 #chaiwalla #pinktea #pinkchai #pinktea🍵 #desi #desitiktok #indiantea

Once this base is ready, salt and milk are added, creating the signature pink color and creamy, savoury flavour that make nun chai so unique.

Interestingly, when Kashmiris migrated to Pakistan, they carried this tea with them, and over time, the recipe adapted to local preferences.

Salt was replaced by sugar and this sweeter version then came to be known as sheer chai or ‘sweet tea’ which is what is served in London, and can be found in popular chains such as Chaiiwala.

Whilst this shift from salt to sugar serves as a testament to culinary evolution, it also represents adaptability to cultural traditions across borders.

At the same time, it is crucial to highlight that while Kashmiri tea is traditionally salty and is now made with sugar in some parts of the world, the sweetened version, in particular, has come to be widely recognised as ‘Kashmiri Pink Tea.’

Yet, for those of us in Indian-administered Kashmir, salty tea is the only pink tea we know and claim as ours.

Nun chai is often described as an acquired taste because of its savoury flavour. And that should not come as a surprise in a world where sugar is treated like some kind of culinary duct tape.

But I suppose that is the charm of nun chai for Kashmiris. We do not necessarily want it to fit in. It may not be everyone’s ‘cup of tea’, but maybe that’s the point. It’s different, it’s ours, and perhaps that makes it enough.