It’s long been posited that money can’t buy happiness – apart from maybe the £9.90 it costs for prescribed antidepressants – but can alienation caused by excessive wealth harm our ability to form interpersonal connections?

The other day I was walking through the display rooms in a well-known, Swedish, affordable furniture retailer, when my best mate pointed out two sinks side by side in one of the show bathrooms.

She made a joke about how nice it would be to be able to brush your teeth with your significant other and to have a sink each.

At the same time it occurred to me how sad it was that being able to afford your own sink – or maybe even your own bathroom – might mean that you miss out on the opportunity to pull stupid faces at someone in the mirror with your mouth full of toothpaste, or else just watch each other dissociate for the prerequisite two minutes, before you go to bed.

Obviously this isn’t the tragedy of the century. Asynchronous flossing is hardly going to be a deal-breaker.

In a similar vein, many couples sleep in separate beds in the same house, or even live completely separately, and have argued that this arrangement is the healthiest and most beneficial for them. There’s even a term for it: Living Apart Together relationships (LAT for short).

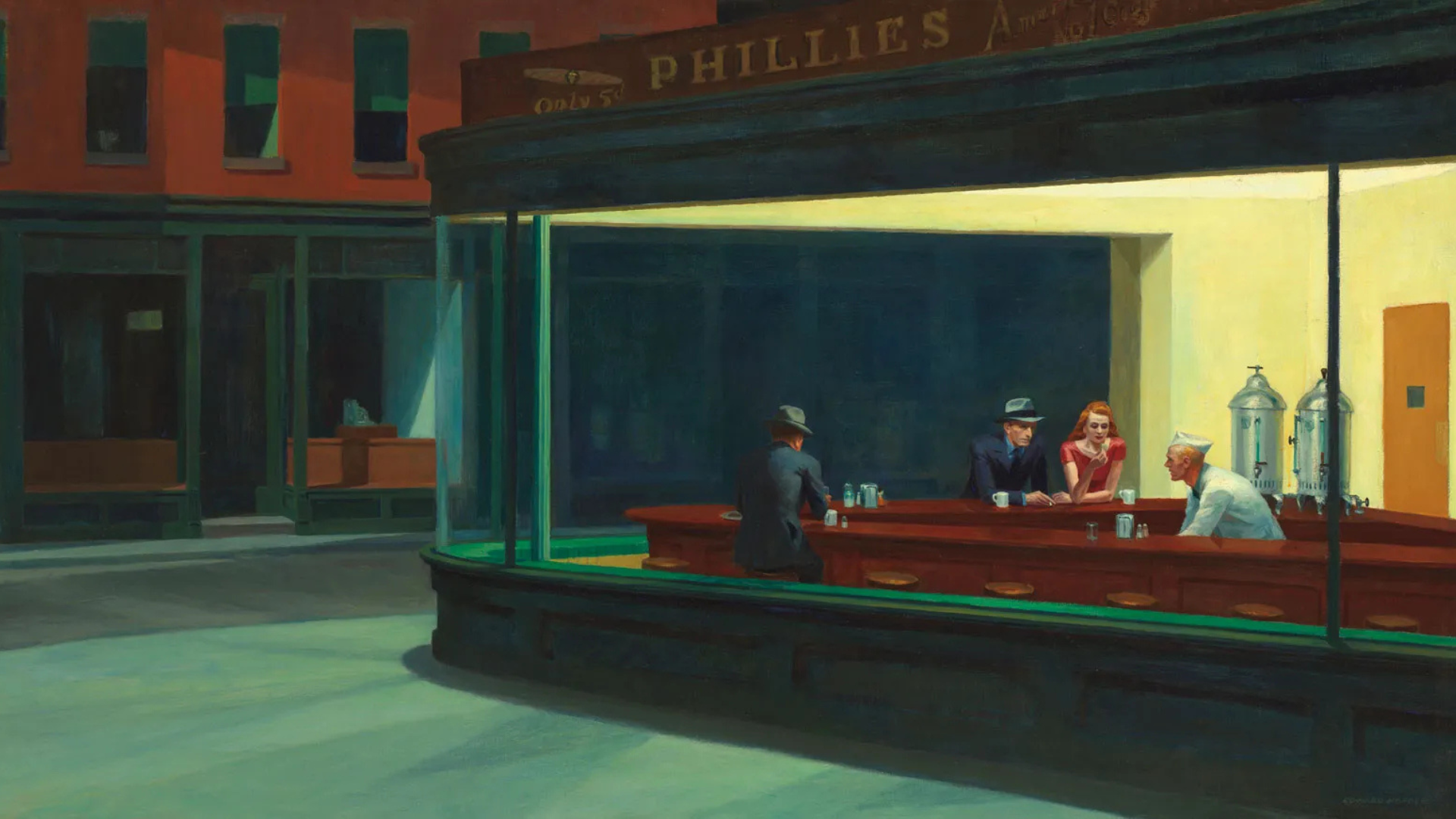

Rathen than running into a sunk-cost fallacy by returning to the sinks, what about all the other ways you might miss out on spontaneous or interesting forms of connection, merely because you can purchase your solitude?

Maybe you Uber somewhere, but what about the missed conversation you could have struck up on the bus?

Or perhaps you book a private room in a hostel, but only down the hallway people from all over the world are meeting and becoming lifelong friends.

I got rich and it’s more lonely than I expected it to be

byu/DotOverTheIBrokeMe inTrueOffMyChest