The last week of November saw an unexpected champion at the Chinese box office. But beyond the numbers, ‘Her Story’ has ignited debates about feminism, representation, and the global lens through which Chinese culture is often viewed.

It’s unusual for a comedy drama, no less a feminist one, to smash records in China’s film industry. For a country known for boosting high-budget action and sci-fi movies at the box office, Her Story defied genre conventions by raking in over 440 million yuan ($61 million) in less than two weeks.

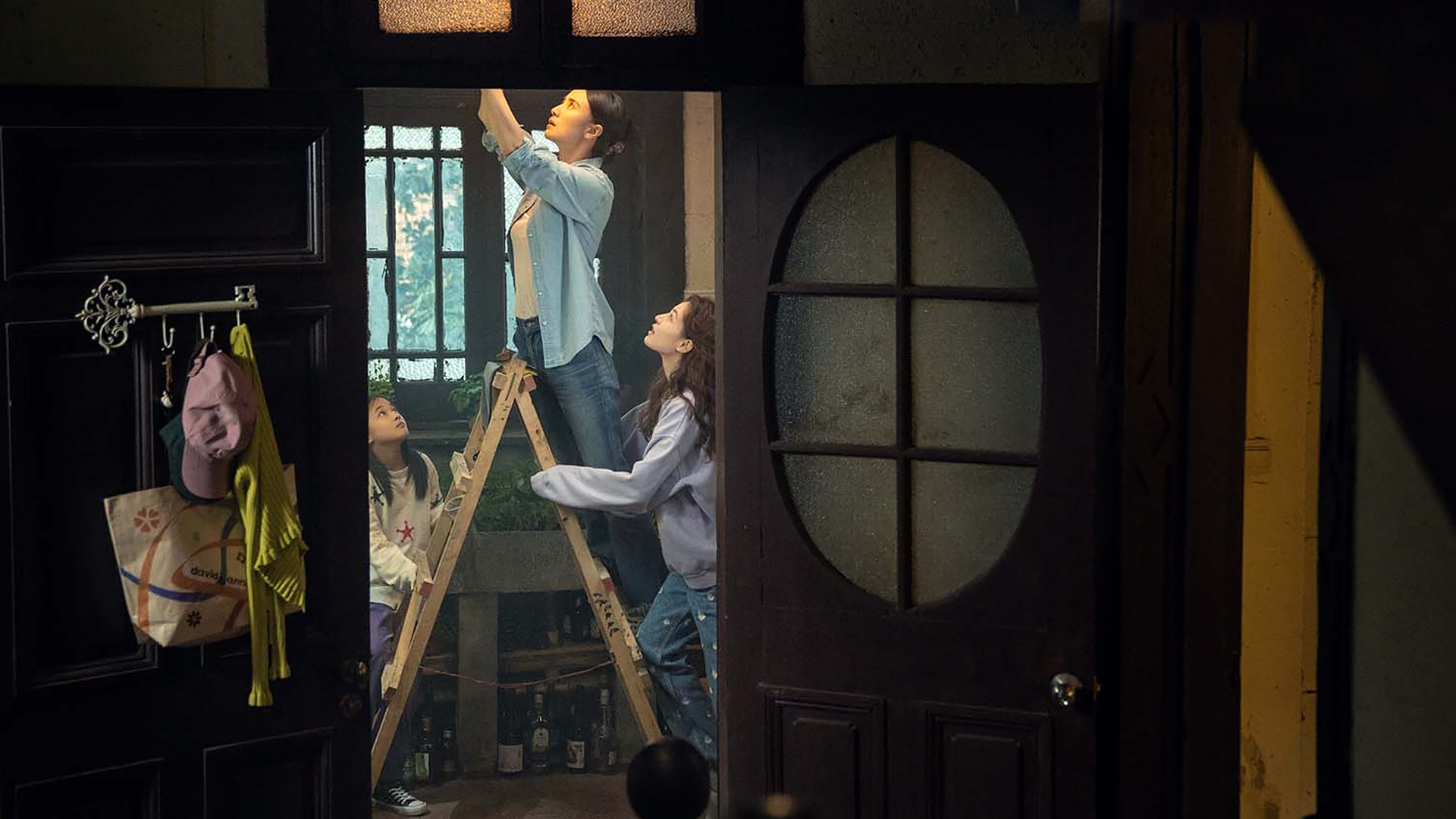

At its heart, Her Story resonates with young Chinese women by diving into experiences that are both deeply personal and profoundly political. The film, which is only the second feature by Chinese director Shao Yihui, deftly explores themes of gender inequality, societal expectations, and the multifaceted struggles of women in contemporary China.

Its humor and humanity have struck a chord with audiences, proving that a low-budget film with a clear-eyed focus on female perspectives can hold its own in a market dominated by spectacle-driven cinema.

But while the film’s success is worth celebrating, its global reception has revealed unsettling biases in how Western audiences and critics interpret Chinese stories. As Her Story gains international recognition, it serves as a mirror for both China and the global misconceptions that often frame its culture and politics.

For any Chinese film, navigating the labyrinth of state censorship is a feat in itself. Her Story’s release and runaway success in this context are particularly notable.

The movie addresses issues like workplace harassment, single motherhood, and the pressures of traditional gender roles, topics that could easily be seen as controversial under the restrictive media regulations of China’s communist government.

However, the narrative that Her Story is somehow groundbreaking simply because it is feminist and Chinese oversimplifies a more complex reality. Commentators within China have been quick to point out that feminist films and discussions are not new to the country.

While the film’s success is significant, it is reductive to treat Her Story as an isolated phenomenon, or worse, as evidence of a sudden ‘awakening’ of feminist consciousness in Chinese cinema.

Chinese social media users have been vocal in critiquing this reductive framing. Movies like Her Story, they argue, are not anomalies in Chinese cinema but part of a broader tradition of storytelling that often includes strong female leads and feminist themes.

‘A normal film in China, but [you’re] really good at picking the material that works for you and making a fuss about it’ wrote one social user beneath an Economist article discussing the film’s success.

The West’s fascination with Her Story reveals less about the film itself and more about the persistent stereotypes that frame Chinese culture as monolithic and resistant to change.

In many Western media outlets, the film is being hailed as ‘China’s answer to Barbie,’ a comparison that feels at once flattering and dismissive.

Yes, Her Story and Barbie both center on women and challenge patriarchal structures, but equating them ignores the distinct cultural, historical, and socio-political contexts in which these films were created.

These narratives perpetuate the tendency of Western audiences and critics to interpret cultural products from non-Western countries through a lens of discovery. This frames progressive ideas as exclusively Western exports, and by doing so, inadvertently diminishes the agency and originality of the creators and audiences within those cultures.

The success of Her Story should be seen as a reflection of China’s evolving societal dynamics.

Feminism in China exists in a unique context – shaped by its own history, policies, and cultural norms. From the women-led protests against workplace discrimination to the rise of feminist discourse on Chinese social media platforms, the film’s popularity is part of a larger movement.

But this is not to say the path is straightforward. The movie’s reception also reveals the constraints within which feminist narratives operate in China. The film deftly avoids confrontational tones that might draw the attention of censors, choosing instead to critique societal issues with humor and subtlety.

The global discourse surrounding Shao Yihui’s film, which features a cast of female leads, mostly highlights the limitations of viewing stories solely through a Western-centric framework.

If Her Story is sparking global feminist conversations, then those conversations must be rooted in mutual respect and cultural nuance.

For Western audiences, this means resisting the urge to simplify or exoticize. It means recognizing that feminist movements and stories can—and do—thrive in diverse ways across the world.

For Chinese audiences, the film’s success is a reminder of the power of representation and the importance of telling stories that reflect everyday realities.

No matter how they are told, stories have the power to challenge norms, provoke thought, and unite us in shared humanity. But they also challenge us to listen more deeply, to look more closely, and to understand each other more fully. That, perhaps, will be this film’s most enduring legacy.