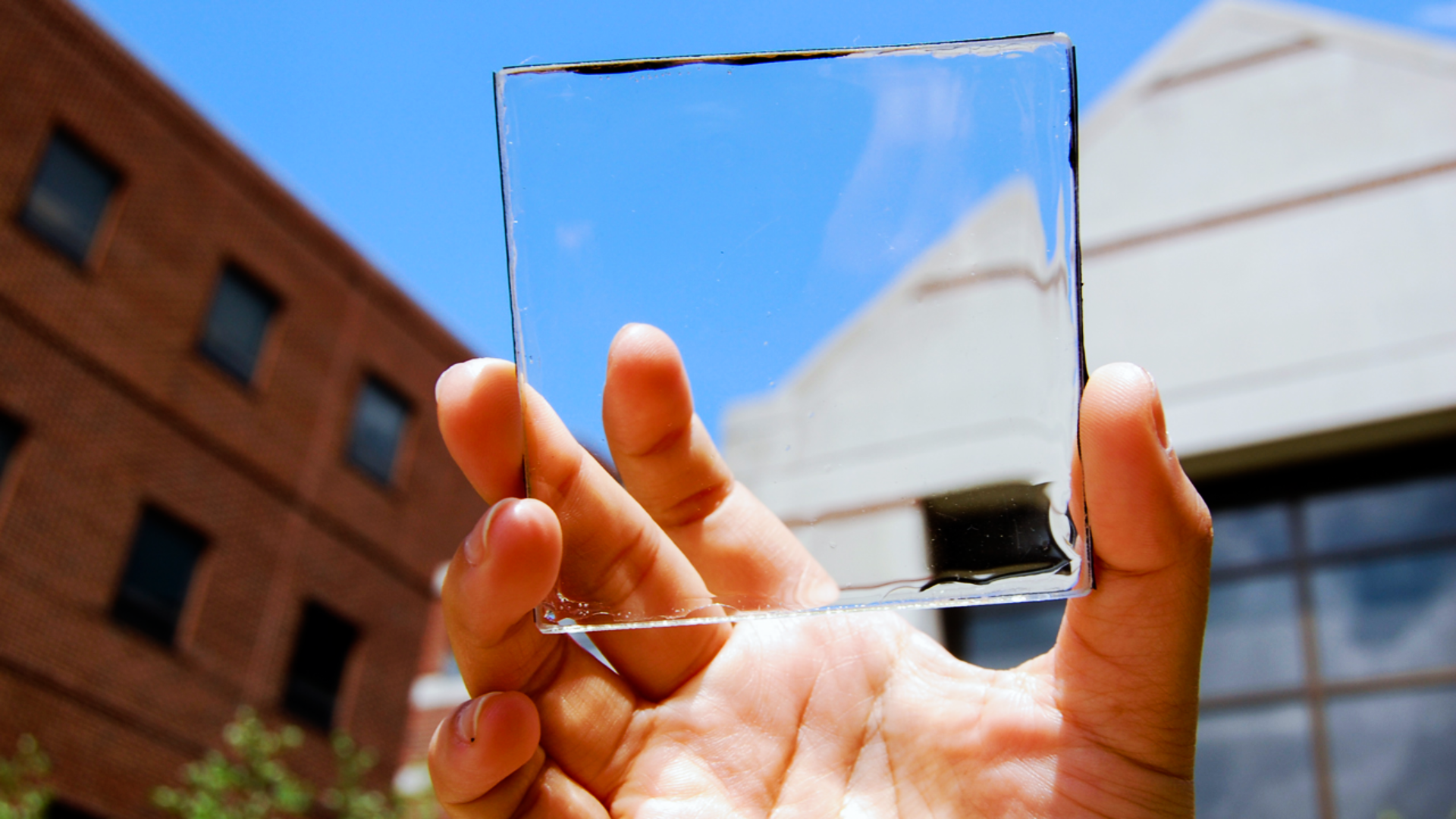

A team of researchers at Michigan State University have just developed the world’s first fully transparent solar window. Is this the beginning of a more self-sufficient future for modern cities?

Imagine a future where the light shining in through our windows actively powers our bulbs when the sun goes down. That’s no longer an entirely unrealistic prospect.

Now, we’re fully aware that windows have technically been integrated with solar technology before – a Filipino based student called Carvey Ehren Maigue won the James Dyson sustainability award in 2020, for his translucent panels comprised of rotting vegetables and special resin.

This is, however, the first instance in which an entirely transparent alternative to silicon (with no tint) has been successfully engineered. When talking marketability, that’s obviously a huge coup.

If you check Google shopping now, you’ll see a few iterations of solar windows already on the market. But, crucially, these are semi-transparent and the clear lines separating strips of solar material within the glass can be seen at close range.

The exciting new material, developed by researchers at Michigan State University, utilises solar cells made from a clear dye-like compound. These are connected to lines of metal so thin that they’re invisible to the human eye.

The first prototype you can see at the top of the page is just small enough to be held by a human hand, but its savvy inventors assure that their process can be scaled up in a factory setting to create fully functional window panes larger than 2 square metres.