If it’s to meet its climate targets, the Netherlands will be forced to choose between agriculture or building new homes and infrastructure unless the farming sector cuts nitrogen-based emissions.

Last year, it was revealed that the agriculture industry is responsible for about a quarter of our total greenhouse gas emissions, the main contributor being livestock and fisheries.

Yet although the drastic environmental impact of meat and dairy production has been at the forefront of the climate conversation for some time now, little has been done to address it – at least from a top down level.

Most often, the solutions posed are targeted towards the individual, encouraging consumers to ‘give Veganuary a go’ or experiment with Meat Free Mondays, for example.

Rarely do we see those in charge of keeping the wheels turning held accountable, let alone forced into changing their ways for the benefit of our planet.

Government officials in the Netherlands have no choice but to adapt, however.

This is due to the Dutch nitrogen crisis, whereby experts are warning that if the country is to meet its climate targets, it will have to decide between agriculture or building new homes and infrastructure, unless the farming sector cuts nitrogen-based emissions.

But why nitrogen? Often, information regarding the industry’s contribution to global warming focuses on the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) emitted during the process of getting a single piece of steak to the dinner table.

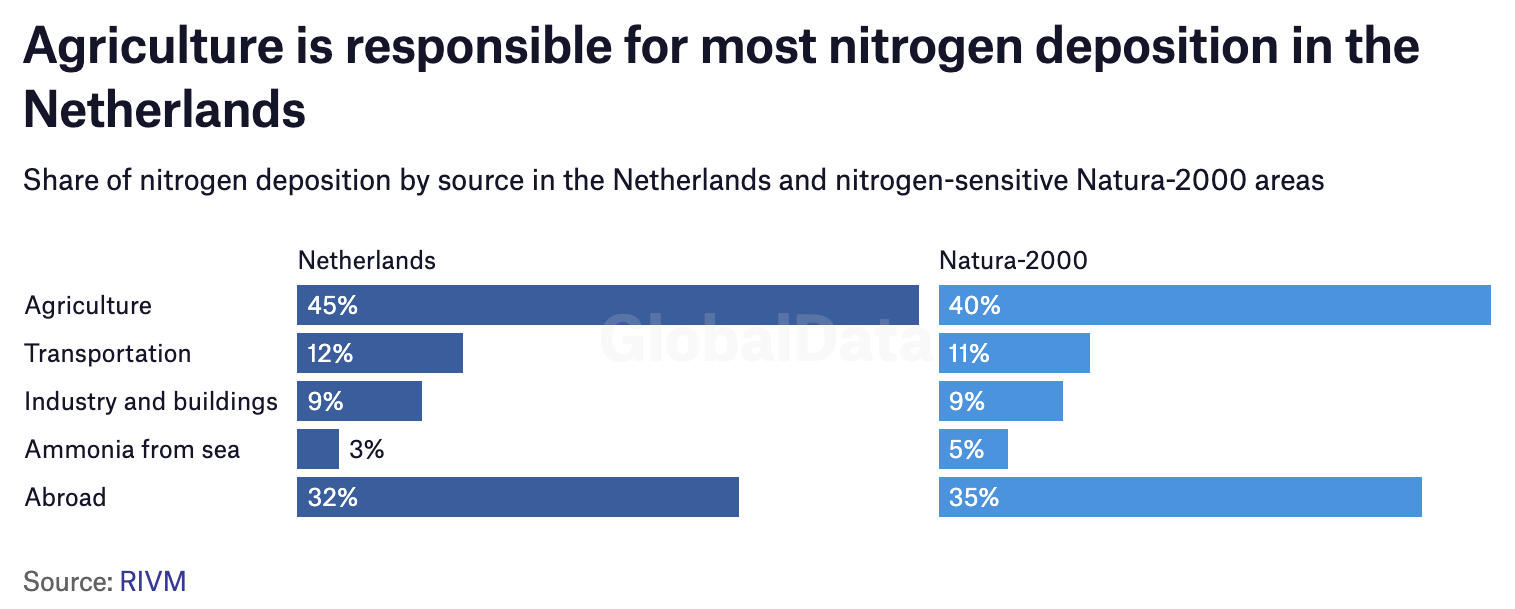

Yet scientists and leaders have recently begun pointing to nitrogen as the ‘lowest hanging fruit’ in the fight to prevent further temperature increases, citing the fact that it’s heavily concentrated on livestock farms, where animal manure is stored and treated in great quantities.

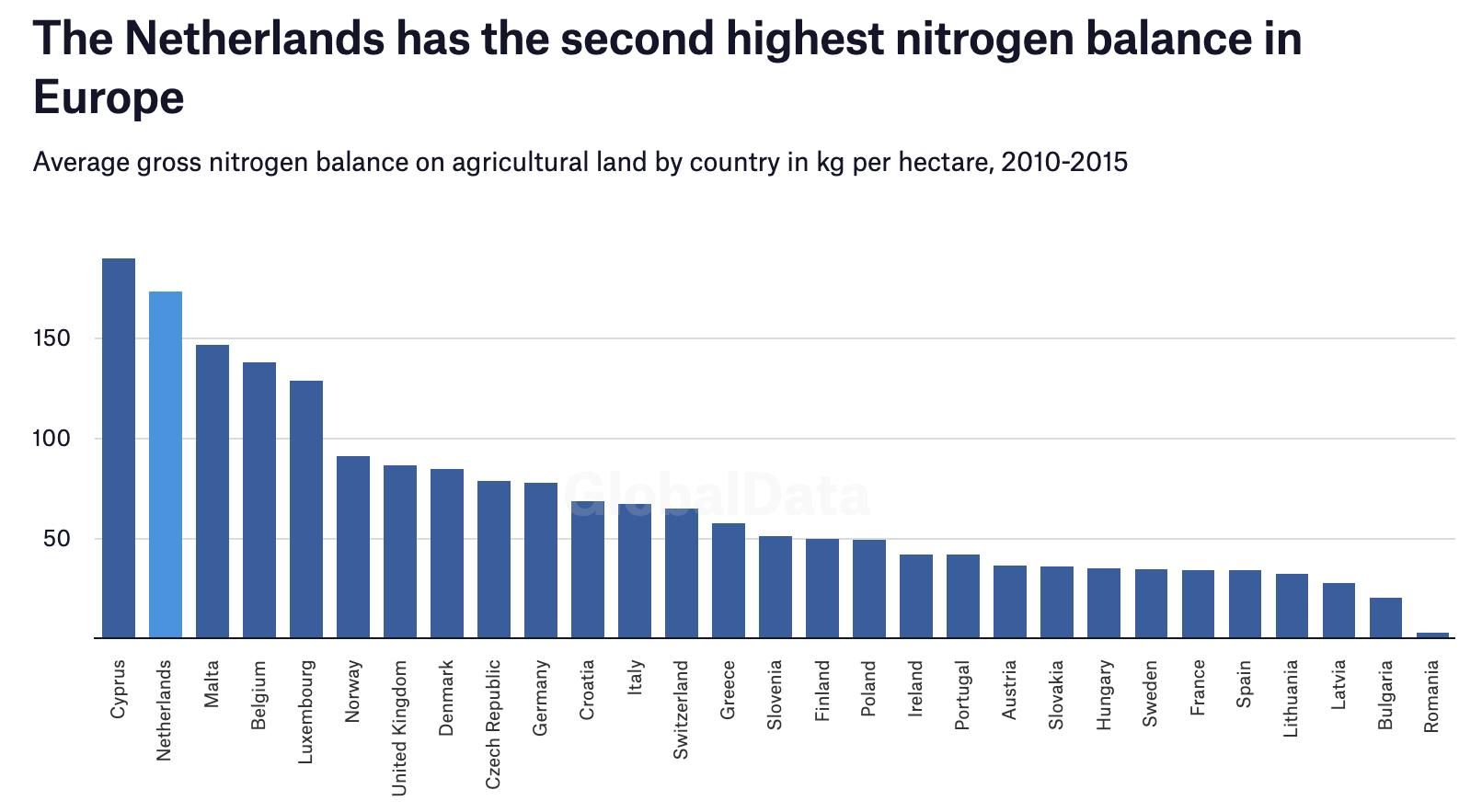

Considering that the Netherlands is the world’s second-largest exporter of agricultural products, that’s a whole lotta biodiversity-destroying nitrogen being pumped into the atmosphere – at a level that’s currently breaking European safety regulations, to be precise.

Raising concerns that such emissions are a big deal in this small, densely populated country and becoming the dominant political issue during the last few years, the crisis has polarised social opinion, spurring the rise of a new rural populist movement and mobilising environmentalists who are worried about the state of wild habitats.

On the back of this, a series of supreme court rulings have brought the Netherlands to a standstill and desperately needed housebuilding has been put on hold for the time being, as builders require nitrogen permits from a limited supply to cover construction emissions.