The vast majority of carbon capture projects that currently turn a profit are reportedly contributing directly to the production of oil. Sigh.

The phrase ‘one step forward, two steps back’ feels particularly apt when delving into the inner workings of carbon capture – in its current form, anyway.

Despite a global consensus that decarbonisation technology is required to remain within the remit of net zero targets, paradoxically 78% of carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects are actually boosting the oil and gas industry.

Every year, roughly 49 million metric tons of carbon dioxide could be manually sequestered – which accounts for around 0.13% of the globe’s 37 billion metric tons created from various industries.

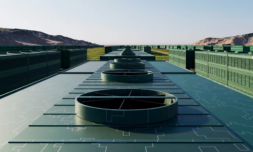

While 42 operational CCS facilities have the potential to reach this volume, a recent report claims that 30 (accounting for 78% of the captured emissions total) are utilising their carbon for enhanced oil recovery.

This process involves injecting the CO2 recovered from, say, an industrial smokestack directly into an oil well to lower the supply’s viscosity and push additional oil to a production well-bore.

In an environmental sense, it’s preferable to drilling for oil in another spot entirely, but it’s far from climate friendly. On the flip side, the remaining 12 companies locking their emissions underground may be doing the honest thing, but they likely aren’t turning a profit. It appears cheaters do in-fact prosper.